The Mexican Modernist exhibition of Leipzig-born Olga Costa’s artworks in the Museum of Fine Arts Leipzig brought colour and vitality to the city during the dark winter months. As the show came to an end I went along to take in the brilliance.

It took 30 years for Costa’s artworks to come home and be truly celebrated here. It is somewhat surprising that, as one of the most popular and important artists of Mexican Modernism, this was the first exhibition in Europe to focus specifically on her work. The exhibition was produced in cooperation with the Instituto Estatal de la Cultura de Guanajuato and the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura (INBAL) in Mexico.

Like many of us, Olga Costa (1913-1993) moved around during her lifetime.

Born as Olga Kostakowsky to Jewish parents who hailed from what is now Odesa, Ukraine, Costa spent her childhood in Berlin during World War I. Her father, a violinist and composer, was persecuted for his socialist political activism, spending periods of time in jail and receiving a death sentence. These challenging circumstances led Costa and her family to flee to Mexico in 1925; she changed her surname shortly after arriving.

In Mexico, Costa began but did not complete studies as a painter. After marrying the Mexican painter, José Chávez Morado, she returned to art at the end of the 1930s. Trips to Europe, North Africa and Asia punctuated her adult life.

You may have seen the glorious 1951 work “The Fruit Seller” on posters around town. The centrepiece and one of the largest of Costa’s exhibited works (195 centimeters by 246 centimeters), it is even more magnificent in the flesh. A fruit seller holds a cut dragon fruit in her outstretched left hand, tempting her customers—and exhibition viewers!—with this and a delicious array of fruit exquisitely arranged on her fruit stand. The detailed scene of everyday life reveals Costa’s interest in the culture of the indigenous people in her adopted homeland. It seems she adopted well to life in Mexico, being embraced as a genuinely Mexican artist by her contemporaries.

What is Mexican Modernism?

In the 1800s, art in Mexico drew on European traditions. For hundreds of years the indigenous population in Mexico was suppressed by Spanish colonial rule, and it was only following the country’s revolution in the early 1900s that Mexico changed radically. Its national identity became a focus, and massive state-commissioned murals in public places were used to help instill national values. Outdoor painting schools in rural areas saw landscapes and scenes of everyday life painted in naïve, figurative forms. This was the complex artistic environment Costa encountered when arriving in Mexico. Added to that was the influence of fantastic imagery, akin to surrealism, which Costa picked up on from her art teacher, Carlos Mérida, her husband and wider network of artists.

The exhibition shows about forty years of Costa’s work along Mexican artists of her time, including Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, Rosa Rolanda, Lola Cueto, Alice Rahon and Juan Soriano. During her lifetime, Costa formed important networks with artists, engaging in initiatives to create exhibition spaces for female artists, like the Sociedad de Art Moderno.

An early self portrait of the artist, her piercing blue eyes turned toward the viewer and a serious expression on her face, draws us into her world. It is a diverse, peopled, but largely natural world. United by a strong sense of complementary colour, particularly reds and greens, the artworks on display are engaging and vary in style and theme.

Olga Costa’s depiction of people

2022 / SOMAAP

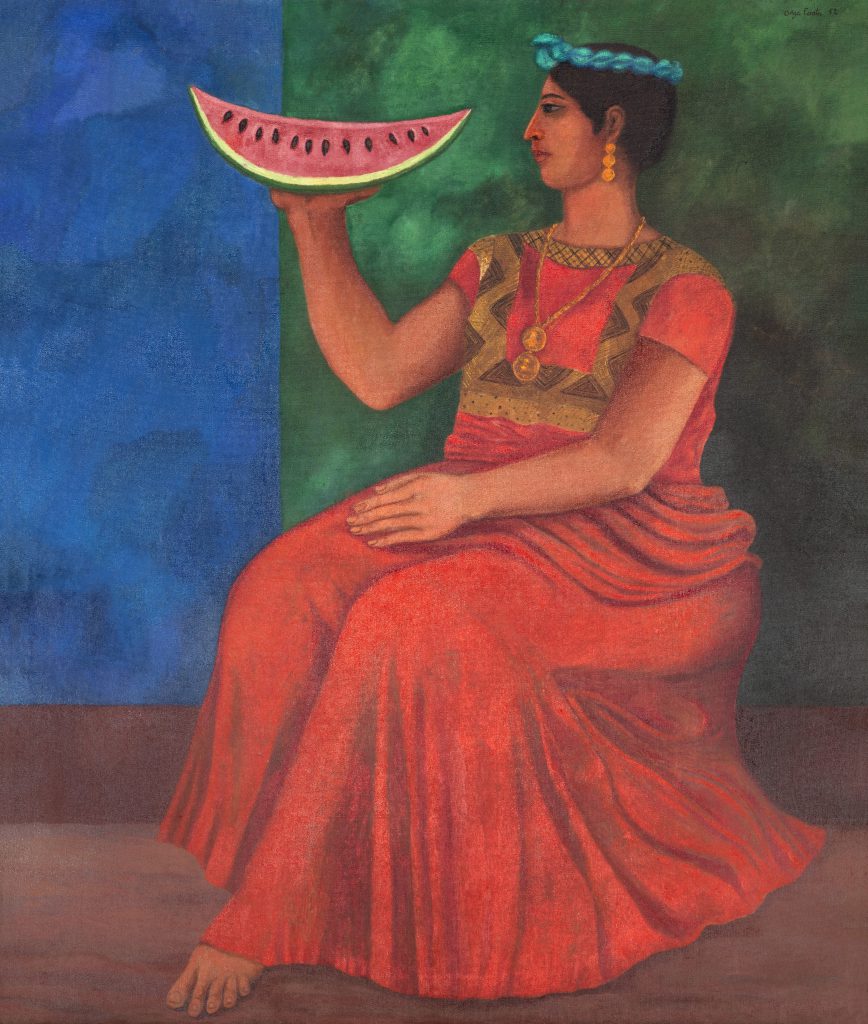

In “Tehuana with Watermelon” (1952), a seated female figure in a full-length orange-red dress with decorated bodice holds up a generous chunk of watermelon. The red of the dress contrasts beautifully against the dark green background, making the figure pop. The woman’s pose appears strong and monumental, almost as if referencing antiquity. It can also be seen to reflect the artist’s feminist tendencies as a woman in an art world largely dominated by men. Similarly, the images, “Girl” (undated) and “Girl with Sandals” (1952) show children larger than life and seated.

Still life

Costa uses the still life form to explore different styles of painting and stimulate the imagination. In “Dried Flowers” (1962), detailed round, brown, spikey flowerheads tumble out of a woven cane basket onto a white tablecloth. The chaotic yet calm composition is appealing. To the right a couple of long black pods containing two red beans leave the viewer wondering . . . do they symbolise fertility perhaps? Intriguingly the same pods and beans also appear in the more surrealist oil painting “Egoistic Heart” (1951). In the still life, “Pumpkins” (1960), seeds are also exposed in a segment cut out of an upright pumpkin. Stylistically different, in this still life blocks of colour are used. The dark green skin of the pumpkin contrasts well with the orange flesh and the reddish-brown dish and background.

Costa and her husband were collectors of beautiful things, and their collections can be seen in several museums, including the Museo Casa de Arte Olga Costa–José Chávez Morado, in Pastita, Guanajuato. Interesting objects often appear in Costa’s artworks. In “Untitled” (1979) a vase in the shape of a statuesque head sprouts a vibrant colourful arrangement of assorted flowers complete with caterpillar, bee and butterfly.

Botanical subjects and landscapes

Botanical subjects abound in Costa’s artworks. Her own lush garden and the surrounding hills and fields where she lived in Guanajuato enabled her to zoom in and out in her artwork. The two ink works “Rock with Lichen” (1974 and 1975) resemble scientific studies in their attention to detail. By contrast her landscapes zoom out to reveal the bigger picture in less detail. It is apparent that Costa’s depiction of landscapes evolved stylistically over time. A more pictorial representation can be seen in the later watercolour of patchwork hillsides, “Landscape” (1973) compared to the curved, organic, textured abstract forms of the oil painting “Arable Fields” (1967)—curiously with one small tree in the left-hand field.

Less common media

While paintings, drawings and prints dominate the exhibition, there are some examples of artworks using less common media. In 1952, Costa created “Marine Motifs,” a large glass mosaic mural for the thermal pool Agua Hedionda. Drawing on traditional examples, the work depicts stylised mermaids, fish, shells and seaweed in a fantastical and colourful underwater world. It was the only mural Costa produced.

Reds and greens dazzle the eye in the undated work “Design for a Tapestry.” The curvy, swirling rather abstract forms fill the vertical rectangular frame and appear inspired by nature. To then see the also undated woven woolen “Tapestry” is a treat. Against a dusky pink background, abstract almost cubist shapes in tones of pink, green, yellow and blue erupt like a geyser into a bouquet of brilliance!

Olga Costa. Dialoge mit der mexikanischen Moderne ran from 1 December 2022 to 26 March 2023. It could be seen in the Museum der bildenden Kūnste Leipzig/Museum of Fine Arts Leipzig, Katharinenstraβe 10, D-04109 Leipzig.

![Wine & Paint event on 9 Nov. 2024 at Felix Restaurant, Leipzig. Photo: Florian Reime (@reime.visuals] / Wine & Paint Leipzig](https://leipglo.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/pixelcut-export-e1733056018933-480x384.jpeg)