Winding up this weekend at the Museum der bildenden Künste (MdbK) in Leipzig is the “Evelyn Richter: A Photographer’s Life” exhibition.

From the 1970s, Richter (1930—2021) gained widespread recognition as an outstanding humanist documentary photographer of East Germany.

This recognition came not only in her homeland of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) but—despite this difficult political climate—also in West Germany and in France.

Indeed, Dr. Jeannette Stoschek, Head of Collections at the MdbK, tells us:

Today Richter is acknowledged as one of the most important photographers of the 20th century.

Her life’s work is celebrated in this retrospective at MdbK alongside that of three of her closest friends and contemporaries: Ursula Arnold, Christa Sammler, and Eva Wagner-Zimmermann, with the latter’s artistic oeuvre being presented here for the first time.

Born in Bautzen in 1930, Richter lived through turbulent times, including National Socialism (Nazi Germany) leading into the Second World War, the division of Germany, and 40 years of the GDR. She lived to photo document the Peaceful Revolution of 1989 and the resulting Reunification of Germany before passing away in Dresden in 2021.

Her photographic career began at 18 years of age with an apprenticeship at a portrait studio, after which she took up a position as a scientific photographer at Dresden’s Technische Hochschule, now the University of Technology, where she also experimented with photography as an art form.

In the 1950s, the East German government brought in strict guidelines restricting abstraction in the arts and gave a directive for what they called “socialist realism.” So, in 1953, when Richter began studying photography at the tertiary level at Leipzig’s Academy of Fine Arts (HGB), the curriculum included scientific photography, advertising, reportage, and portraiture. That was because photography was largely considered a tool for the publishing industry and the illustrated press, rather than an art form.

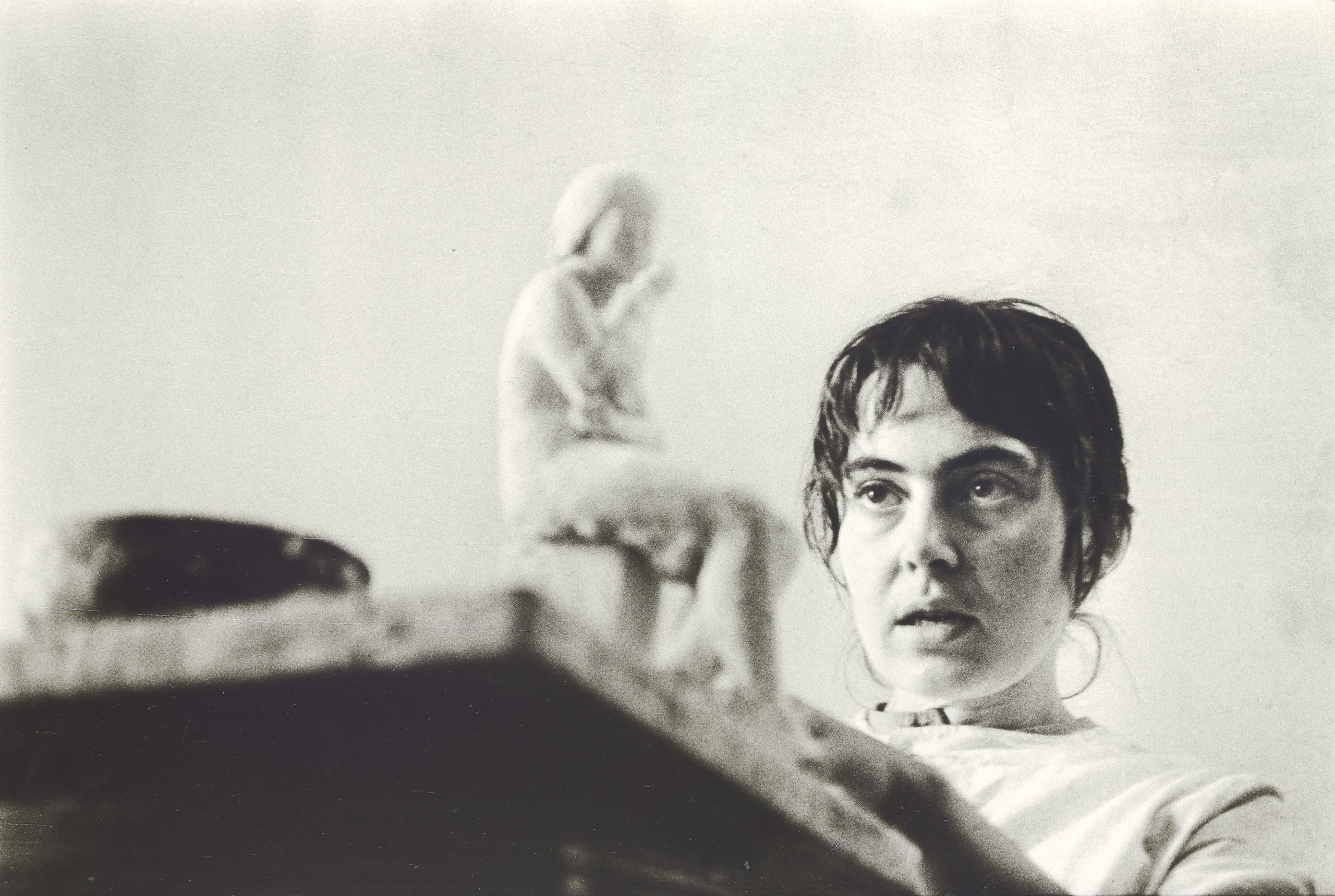

The MdbK exhibition presents black and white photographs by Richter from this period, capturing the spirit of student life and her experimental style, including portraits of fellow students.

An open-minded and ambitious student, Richer became increasingly dissatisfied with the restrictive curriculum and threw in the towel after two years of studies, setting out instead into the world of freelance photography. In a twist of fate, Richter returned to the HGB in the 1980s as a lecturer, where she was given an honorary professorship.

The main part of the exhibition focusing on Richter’s oeuvre is displayed in the basement, in arguably some of the MdbK’s nicest exhibiting spaces. Here her career is broken up into three main bodies of works, namely her self-portraits, photojournalism, and photobooks.

Richter was a pioneer of the photobook, which offered her the ideal basis to define and present her picture concept as a composed series and to develop a narrative picture structure. Her book on the German composer and conductor Paul Dessau and her non-fiction book Entwicklungswunder Mensch (“The Human Being a Miracle of Development”) are presented in the form of layouts, proofs, and portrait photographs.

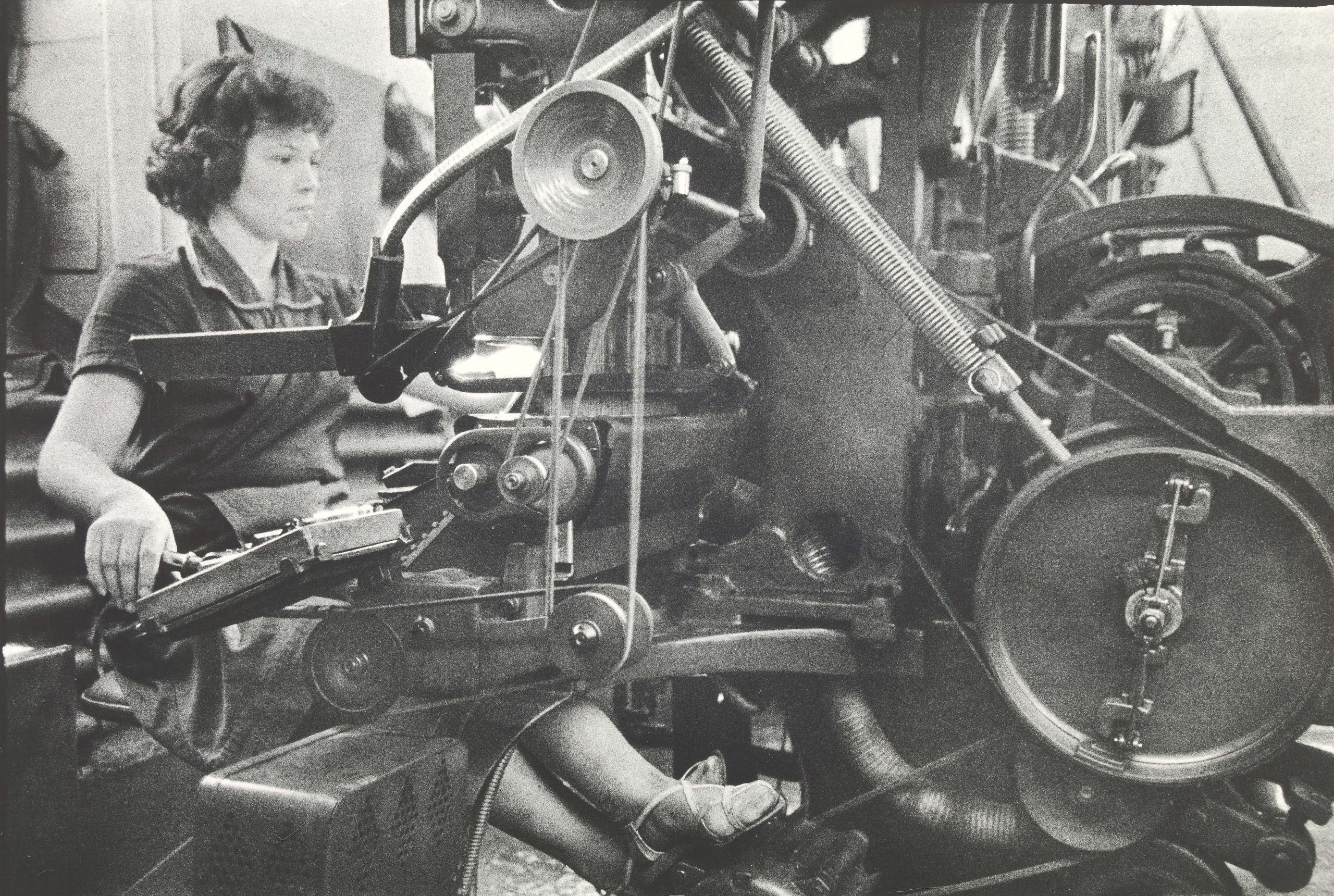

Displayed here for the first time in her unrealized book project “Women in the GDR,” we see stunning portraits of women in their places of work, a testament to the equal contribution to the workforce that East German women were afforded. Women at work became a principal theme for Evelyn Richter throughout her career.

The photojournalism section of the exhibition makes poignant the conundrum that photographers of that era faced.

Photographs were not exhibited in galleries or on the art market and photographers, Richter included, were forced to accept commissions from magazine editors and publishers. Richter also took on commissions from theatres and the Leipzig Messe to make ends meet, thus funding her own freelance projects. Many of these commissions have now become an intrinsic part of her oeuvre, forming part of her own visual language.

On the third floor of the gallery, the exhibition continues across three rooms with the three friends of Richter, their varied life journeys and differing professional careers.

Like Richter, Ursula Arnold studied at the HGB and worked as a freelance photographer. Here in 1953, the two met Eva Wagner, as she was then called, and the three of them quickly became friends. They took images of each other within the university, as photographing outside in the city was still forbidden while it still carried the heavy scars of war.

Arnold became a camerawoman for German television. Eva Wagner, on the other hand, married the physicist Wolfhart Zimmermann in 1957 and devoted herself to her family, having had her images rejected multiple times by editors. She often accompanied her husband on his trips abroad, photographing everyday life on the street—in Mexico, Paris, and New York.

This exhibition is the first time that the artistic oeuvre of Eva Wagner-Zimmermann has been presented to the public.

The circle of friends was completed in 1957 by the Berlin-based sculptor Christa Sammler, who is depicted working in her studio in Richter’s photo series “Women in the GDR.”

The multifarious career paths of these four women address the question of how women of their generation were able or unable to become active as artists in their chosen mediums. What is clear is that these foundational friendships created an enduring artistic environment in which they could each be seen and heard.

The exhibition catalogue is available in a German and an English edition. The volume, with 212 pages, numerous illustrations and texts by Linda Conze, Florian Ebner, Philipp Freytag, Sandra Starke, Jeannette Stoschek, and Jan Wenzel is available for €42 in the museum store and in bookstores.

![Wine & Paint event on 9 Nov. 2024 at Felix Restaurant, Leipzig. Photo: Florian Reime (@reime.visuals] / Wine & Paint Leipzig](https://leipglo.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/pixelcut-export-e1733056018933-480x384.jpeg)