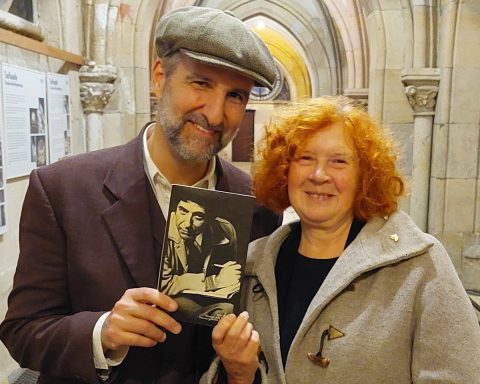

I recently interviewed Nadia Parfan about her documentary film, “I did not want to make a war film.” At that time, she told me the current Russian invasion of Ukraine had not come out of the blue, and we began to talk history. On this topic, I recently took in the exhibition “Independence! Photographs from Ukraine, 1991–2022” at the Zeitgeschichtliches Forum Leipzig.

The exhibition provides a great opportunity to explore this tumultuous period of Ukraine’s history. And, if a picture can tell a thousand words, the photos do a brilliant job depicting Ukraine’s struggle for autonomy, national identity and democracy during the 21-year period.

“Independence” is divided neatly into four parts.

In the main room the chronological order proceeds in an anti-clockwise direction. It covers from Ukraine’s independence in August 1991 to the beginning of Russia’s full-scale attack on Ukraine in February 2022. Words are used sparingly, and the photos by notable Ukrainian photographers are taken close to the action. In doing so, they capture incredible expressions on faces using a generally subdued palette of browns and greys punctuated by intense red. The mass gatherings in solidarity, and in conflict between sparring groups, contrast with heart-breaking images of vulnerable individuals in desperate situations. But there are also moments of light among the dark.

A new country emerges

Leonid Kadenjuk, the first astronaut of the independent Ukraine, looks on determinedly as his helmet is adjusted in Florida on 5 November 1997. Sergei Bubka, Ukrainian Olympic champion and multiple World and European Champion pole vaulter uses all his strength to heave himself high at the World Athletics Championship in Göteborg on 9 August 1995. These images are symbolic of what Ukraine had become since the country declared its independence on 24 August 1991.

However, as the exhibition information board explains, withdrawal from the Soviet Union meant dealing with a legacy of outdated industrial plants, widespread corruption and a large nuclear arsenal. On the latter point, in 1994 Ukraine handed this inventory over to Russia. In exchange, Russia, the United States , and Great Britain guaranteed Ukraine’s independence.

While cohesion grew in Ukraine the question of whether its future orientation would be towards Western Europe or Russia caused division . . .

Fight for democracy

In the exhibition’s main photo, a woman with a wreath of fire engine red flowers around her dark hair and a floral scarf across her nose and mouth dominates against a backdrop of smoke and flames. Her exposed eyes do not show terror but a calm determination as she participates in the Maidan Uprising on 18 February 2014. Black and red are the predominant colours and they heighten the dramatic effect in this image of beauty and courage in the face of danger.

Rewinding a little, in 2004 the Ukrainian presidential election brought about a decision on the country’s direction. You may know the names of the candidates: Viktor Yushchenko, who oriented himself towards the west; and Viktor Yanukovich who was considered the candidate for Russia.

The exhibition board explains the outcome:

“Yanukovich eventually declares himself the winner. But large portions of the population are not ready to accept the obvious electoral fraud. Weeks-long protests in the colours of the opposition give the movement the name: The Orange Revolution. It forces a repeat of the election, from which Yushchenko emerges as the winner.”

An image shows someone peeking out of their makeshift tent on 22 November 2004 at the somewhat organised chaos that has become tent city on the Square.

Fast forward 10 years, and the pro-Russian government of the time stops a planned agreement with the European Union which would have more closely integrated the EU’s ties with Ukraine. In protest, the Maidan Uprising takes place on Kyiv’s Independence Square, claiming the lives of more than 100 people in bloody street fights.

Ultimately, the president loses his power and flees. The exhibition’s information board states, “A new government must solve old conflicts.”

Defending independence

Two young children holding hands gaze upwards from the bottom of a bare concrete stairwell, the pink and red of their clothing providing a touch of colour in the dark environment. They are seeking shelter from air raids during Russia’s attack on Ukraine that began in the spring of 2014. That they are scared shows on their faces; this is clearly no place for children. The attacks do not discriminate based on age, and in another poignant photo we see predominantly women inside a bus fleeing their city of Debalzewe on 3 February 2015. An older woman in front on the viewer’s right has obvious injuries—with a spot of blood on her nose she covers her left eye with a badly grazed hand. Meanwhile her right eye looks hauntingly at the viewer.

In 2014, Russian special forces, referred to as “the little green men” due to their unmarked uniforms, occupy Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula. Initially denying that the soldiers are in fact special forces, Russian President Vladimir Putin incorporates the strategically important peninsula into Russia’s national territory, contrary to international law. In the east of Ukraine, pro-Russian militia, supported by regular Russian troops, fight for secession of the Donbas from Ukraine.

The horror continues in July 2014 when a Russian air defence missile strikes a Malaysian Airlines plane, killing all 298 people on board, including 80 children.

The Minsk Agreements of 2014 and 2015, mediated by the leaders of France and Germany, see the fighting in the region subside but not completely cease. In early 2022, tensions between Russia and Ukraine heighten, and Putin declares that the Minsk agreements no longer exist. He says Ukraine, not Russia, is to blame for their collapse.

A country at war

On 3 April 2022 a bride and groom in Charkiw fiercely embrace among the ruins of war on their wedding day. The moment of intense happiness is rare among the photos on display. It contrasts with an image of a little boy whose big eyes look up at the viewer over his Mum’s shoulder in a gloomy makeshift air raid shelter on 7 March 2022. Sadly, this is rather the order of things in a time of war.

On 24 February 2022, Russia begins its invasion of Ukraine. Putin calls the attacks on the neighbouring country a “special military operation.” However, the plan to quickly take Kyiv and bring down Volodymyr Zelensky’s Ukrainian government fails rapidly.

The Ukrainians hold their ground, despite the destruction of infrastructure and relentless attacks on civilian facilities including hospitals, residential buildings, schools and theatres. “Bucha and Mariupol become the embodiment of the ruthless Russian warfare” the exhibition information board states. But as the war continues it appears the Russian invaders have underestimated the courage and stamina of the Ukrainians in resisting and defending their home and their independence. After all, they have had practice doing so.

Independence! Photographs from Ukraine, 1991–2022

Where: Zeitgeschichtliches Forum Leipzig, Grimmaische Straβe 6, 04109 Leipzig

When: 24 February to 2 July 2023. Tuesday to Friday, 9 am to 6 pm. Saturday, Sunday and holidays 10 am to 6 pm

Question session every Saturday between 2 pm and 4 pm at the exhibition, and on 8 May from 7 pm to 10 pm

Cost: Free

![Wine & Paint event on 9 Nov. 2024 at Felix Restaurant, Leipzig. Photo: Florian Reime (@reime.visuals] / Wine & Paint Leipzig](https://leipglo.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/pixelcut-export-e1733056018933-480x384.jpeg)