As cathedrals go, the Frankfurter Dom is not the most beautiful or splendid. But for a moment last month, it might just have been the most important in the world and in the history of the Catholic Church.

A ground-breaking exhibition named mitten unter uns (“in our midst”) graphically displayed the true extent of sexual violence against women, men, and children—abuse Catholic Church authorities have covered up for decades.

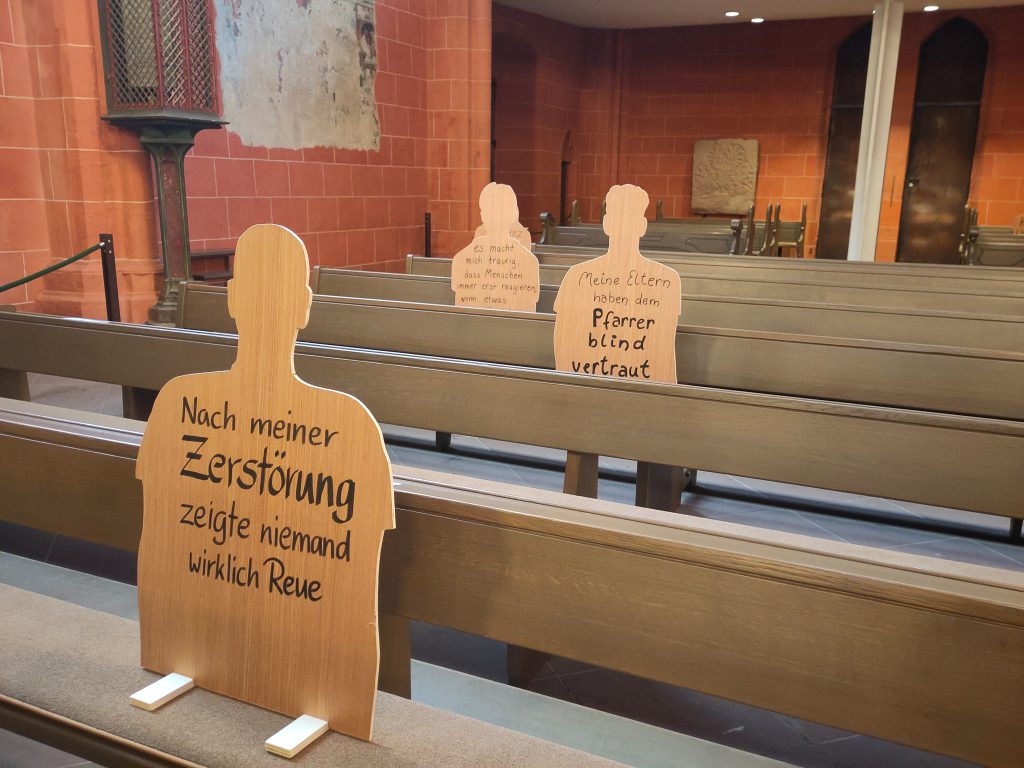

Upon entering the cathedral, visitors were met with a striking sight: Each pew had at least one life-size, flat wooden figure seated among worshippers, tourists, and those seeking shelter from the rain. The figures—representing children, women, and men—were anonymized but clearly based on real people. Each figure bore a handwritten message drawn from the testimony of real abuse victims.

Some visitors may have recognized their own painful experiences reflected in the figures. Here they could also find shelter from the storm of emotions—shame, rage, despair, and loss of faith—along with the spiritual turmoil unleashed by the betrayal of trust from those who claimed to do God’s work on Earth.

For those in need of support, a helpdesk staffed by counselors was available at the entrance to the exhibition. Visitors who did not wish to seek help could instead leave written feedback or request further information. Handouts were available in German, English, and Turkish, ensuring accessibility for a broad audience. The organizers aimed to reach a wide range of visitors, knowing that 10% of Germany’s population had experienced sexualized violence—many in Catholic contexts such as choirs, Sunday schools, and youth clubs.

Fact Box: Abuse in Germany and the Catholic Church

- 2023: 12,186 cases of sexualized violence were investigated by police in Germany, compared to 7,408 cases a decade earlier (Statista). Many cases remain unreported, so the true figures may be higher.

- A free, confidential helpline is available for those who wish to report abuse in Germany.

- The Catholic Church in Germany acknowledges that 1-5% of clergy have been involved in sexualized violence (katholisch.de). Since individual priests often abuse multiple people, the percentage of victims is likely even higher.

- For the Frankfurt exhibition, organizers estimated that 10-12% of the general population (not just churchgoers) have experienced sexualized violence. To illustrate this, they filled one-tenth of the church’s pews with wooden figures.

Confronting the role of Pope Benedict XVI

The role of former German Pope Benedict XVI (Joseph Alois Ratzinger, who served as pope from 2005 until his resignation in 2013) in covering up cases of abuse has been widely criticized. His handling of the crisis stained his legacy and may have contributed to his early resignation. Debates within the Church have often focused on the cover-up and allocation of blame.

However, the exhibition in Frankfurt represents a significant shift: Instead of focusing solely on the Catholic Church’s failings, it places the voices and experiences of victims at the forefront.

One small wooden figure poignantly declares, “I had such a little soul, such little hands.” Positioned next to a stone statue of a tall, overweight bishop in ornate robes and mitre, the contrast is stark and symbolic.

Nearby, an adult male figure carries the haunting words: “After they destroyed me, no one showed any real remorse.” Such words have been reverberating down the years since news first broke of the sex abuse scandal in Germany.

A small boy’s figure recalls his struggle to be believed: “My parents trusted the priest blindly.”

A teenage girl’s figure voices the fear that so many victims feel: “What’s he going to do to me this time?” The anxious question carried by the shape of the girl tells us that these are not just isolated incidents or lapses by priests, who must take a vow of celibacy.

Towards the back of the nave, an older woman’s figure confesses: “I’ve been carrying my pain for many years now.”

Finally, a life-size figure of a teenager sums up the experiences of many in just two words: “Screaming silently.”

Efforts towards accountability and healing

The exhibition was sponsored by the bishoprics of Limburg and Fulda. It complemented another initiative hosted in the church-owned Haus am Dom, a conference hall next to the cathedral. Titled “Victims Show Their Faces,” the exhibition featured photographs of adult survivors of sexual abuse by priests, teachers, and church-affiliated youth workers. The images, while posed to protect anonymity, gave a human face to the stories of pain and survival.

At its conclusion, high-ranking Church officials hosted a public debate on the crucial question:

How can theology help to respect the basic needs of people who should have been under the protection of the Church and restore justice after the abuse of power?

The Frankfurter Dom exhibition served as part of the answer. It was both a confessional and an invitation. It encouraged more victims to come forward, to confront the facts and figures behind the abuse scandal, and to make their suffering visible. Supported by on-site emotional, psychological, and spiritual assistance, it represented a powerful gesture of accountability. Or did it?

A timely initiative or too little, too late?

Despite its good intentions, the exhibition may be seen as too little, too late. The Catholic Church has continued to lose thousands of members each month as more people become disillusioned by revelations of abuse and the institutional secrecy that enabled it, among other considerations. The Church’s acknowledgment of its failures and its efforts to promote healing are important steps, but they may not be enough to restore faith in the institution.