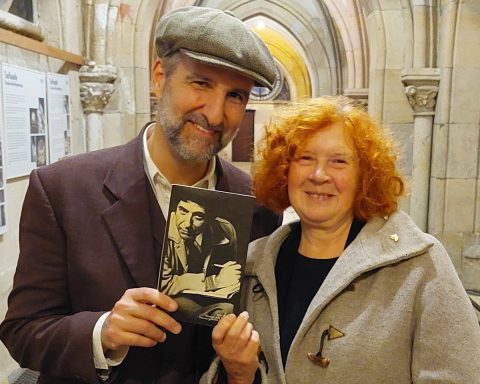

Text and Q&A by Felipe Cherubin

I’ve interviewed American psychiatrist Allen Frances, Professor Emeritus at Duke University. Our talk revolved around a very old and thought-provoking question: What is normal?

The DSM (Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of Mental Disorders) provides a standard criteria for the classification of mental disorders. We are currently separated between “normal” and “abnormal” by the DSM-5, the bible of psychiatry. Frances, who served as chair of the DSM-IV taskforce and as contributor to other previous versions of the manual, is now a leading opponent of the changes in the fifth edition.

He contends they “medicalize normality,” without enough to back it up.

Frances reports that with the DSM-5, psychiatry entered a kind of collapse: The version was drafted in a way so irresponsibly without solid and scientific criteria, that we are now facing an instrumentalization of human sanity. So, with loose criteria, psychiatry becomes an accomplice of nefarious interests.

At center stage is the pharmaceutical industry, which, according to Frances, represents a comparable force to what the tobacco industry was 30 years ago. His last book – “Saving Normal: An Insider’s Revolt Against Out-of-Control Psychiatric Diagnosis, DSM-5, Big Pharma, and the Medicalization of Ordinary Life” – is a protest against precisely the pharma industry and the abuse of medicine.

Our interview touches on these issues, turning to the political and economic powers behind a dynamic that affects all of us, our health and, perhaps above all, our hopes and prospects for the future.

Felipe Cherubin: With your experience in compiling multiple versions of the DSM, which are the points you think need to be rethought to improve reliable psychiatry as a branch of medicine in the future?

Allen Frances: The most important things are to reduce over-diagnosis and over-treatment and to increase the access to care of the really sick. A psychiatric diagnosis often lasts a lifetime and should be done with the same care as choosing a spouse or a house. Done well, psychiatric diagnosis can dramatically change a life for the better; done poorly, it can do great harm.

FC: What changed, and why be careful with the DSM-5 publication?

AF: The DSM -5 definitions of mental disorder are too loose and drug companies exploit them to peddle pills. It is in their interest to sell the psychiatric [cases as] ill as a way of peddling their pills. Normal distress that is part of the human condition should not be mislabeled as a mental disorder.

We are experiencing a cruel paradox: Essentially normal people who don’t really need medications are taking far too many, while we neglect the people with severe mental illness who often have no access to treatment they desperately need.

FC: Your book breaks the silence and shows the alarming situation in which psychiatry is involved. Who should care if this situation persists?

AF: The fight against the under-treatment of the severely ill is a difficult one because they are vulnerable and have few champions. Mental health budgets to provide them with adequate treatment and housing are always underfunded by politicians.

The fight against over-treatment is equally difficult because most psychiatric medication is prescribed by primary care doctors who have little expertise in psychiatry and too little time to really get to know their patients. The easiest way to get a patient out of the office is to prescribe a pill, even though there is not a pill for every problem.

FC: You say that your criticism is directed to the excesses of psychiatry and not their essence. These excesses are possible only with the omission of the psychiatrists once they are the authors of the final decision. Is there any kind of pressure putting at stake their reputations and even their jobs?

AF: I have worked with thousands of experts on all of the psychiatric disorders, and not once has any ever said: “Please narrow the definition of my disorder.” Experts always favor their pet disorder, worrying too much about missed diagnoses and too little about over-diagnosis. Intellectual conflicts of interest are much worse than financial conflicts of interest, because they are more frequent and harder to identify.

FC: The philosopher Socrates said in Plato’s “Apology” that “The unexamined life is not worth living for a human being.” This quotation brought up the question of self-consciousness as an acute sense of self-awareness. Is there a scale of self-awareness and, if so, how does this help us?

AF: At this point, I think the problem may have flipped: Too many people have become excessively self-absorbed and self-aware. Life should be lived as well as thought about, and consciousness may be overrated.

FC: Do you believe that what we call “mental illness,” such as Asperger, autism, schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder, and so on, can be “problems” that all of us have a bit of everything, but within a different spectral scale?

AF: All of us have psychiatric symptoms from time to time, but not enduringly, and not at a sufficiently severe level of distress and impairment to be considered a mental illness. There has been a unfortunate loosening of diagnostic standards – leading to excessive treatment with psychiatric medication of people who don’t need it. This results in a paradoxical misallocation of resources, [in which] those with severe illness who desperately need medication often are neglected.

FC: You talk about normal human behaviors that end up being diagnosed and understood as psychiatric diseases. Could you give examples of how normal human actions have been justified by psychiatry not as social problem, but as a medical problem?

AF: Normal immaturity becomes Attention Deficit Disorder. Normal grief becomes Major Depressive Disorder. Normal forgetting of old age becomes Minor Neurocognitive Disorder. Overeating becomes Binge Eating Disorder. Temper tantrums become Disruptive Mood Deregulation Disorder. Medical symptoms become Somatic Symptom Disorder.

FC: Following Huxley’s insights in “Brave the new world,” you identify that the marriage between the pharmaceutical industry and medicine are undermining the pillars of a just and democratic system. As a society, how we could face economic and political powers that begin to impose tyrannical practices in what we call “free societies?”

AF: Drug companies today are in the same position as the tobacco companies 30 years ago – enormous political power protecting outrageous commercial behavior. The tobacco companies seemed invulnerable, but fell because right sometimes makes might. Big Pharma controls the politicians now, but the public and media may eventually help win this David vs Goliath battle.

FC: Why do some cultures and societies need “victims” to justify their systems?

AF: It is easier to treat sick people than sick societies.

FC: What do you think about genetics and the future of psychiatry?

AF: Genetics is a fascinating area of study, but will provide no easy answers. The brain is the most complicated thing in the universe, with more neurons than there are stars in our galaxy, and 100 trillion neuron connections. Neurons that fire together wire together in ways that are not closely controlled. Studies consistently find genetic relationships to psychiatric disorder, but they are essentially meaningless because it is hundreds of genes, each just a tiny bit more or less expressed than normal.

The permutations are dizzying. So far, the wonderful advances in the understanding of neuroscience have not helped a single patient. Because the brain is so complex, there is no low hanging fruit, no easy breakthrough.

FC: You mention Freud in your book. Are we facing abuses also in the field of psychological therapy?

AF: I think therapy is underutilized and should be more readily available.Brief psychotherapy is as effective as medication for most mild to moderate psychiatric problems, and is more enduring in its benefits.

FC: In the 90s, musician Kurt Cobain, the idol of a generation, killed himself. This resulted in a series of suicides of Nirvana’s dismayed fans. Is this kind of behavior something new in history?

AF: Cluster suicides are frequent in history and go by the name “Werther Syndrome,” after the hero of a book by Goethe that set off a wave of copycat suicides in Europe during the late 18th century.

FC: Art and literature can reveal humans’ deepest personality. Who are your favorite artists and writers showing the mystery of human nature?

AF: James Joyce’s “Ulysses” is the most complete and most beautiful portrait of the human experience.

FC: Considering your life experience, what is your definition of intelligence?

AF: Not making the same dumb mistakes over and over again.

FC: You visited Brazil recently. What are your impressions on the Brazilian approach to mental illness treatments? Did you perceive some differences in our country, compared with the situation in the US?

AF: The goals and methods for helping the severely ill are perfect, but terribly underfunded. The excessive use of medication for normal distress is almost as bad [in Brazil] as in the US. You are now experiencing many economic, social, and political problems – these require economic, social, and political solutions. Taking psychiatric pills doesn’t solve normal distress and often causes more harm than good.

FC: You report many very interesting real cases that certainly will appeal to the readers. Recently I witnessed a reality that I never imagined, visiting a research project on bipolarity. I was amazed at the high incidence of bipolar couples (even in friendship). Couples also reported being afraid of pregnancy, since bipolarity is a genetic illness. Can you comment on these points?

AF: It is not surprising that people with Bipolar Disorder are more likely to meet and be attracted to each other. And yes, this does significantly increase the risks of troubled marriages and children with a predisposition to Bipolar Disorder. People have to make their own decisions, and love often (for better and worse) does conquer all, but everyone should be aware of the risks.

FC: Finally, if you want to add any comments that you think are of utmost importance, I would be very grateful.

AF: Never give up hope. I have seen many remarkable turnarounds from what seemed to be hopeless illness and desperate life situations. If you put your heart into it and your doctor puts her heart into it – and if everyone is patient and systematic – there is a good chance for a positive result.

I have learned most of what I know about psychiatry and about life from my patients. So, we need to provide care and dignity for the mentally ill, and equally, we need to avoid medicalizing all the expectable difficulties of the human condition.

Felipe Cherubin is a philosopher, journalist and writer based in Brazil. He graduated with a degree in law and philosophy, studying at the Catholic University of São Paulo (PUC-SP) and Harvard University. He is author of the book “O que é a Inteligência? Filosofia da Realidade em Xavier Zubiri,” in partnership with José Fernádez Tejada.