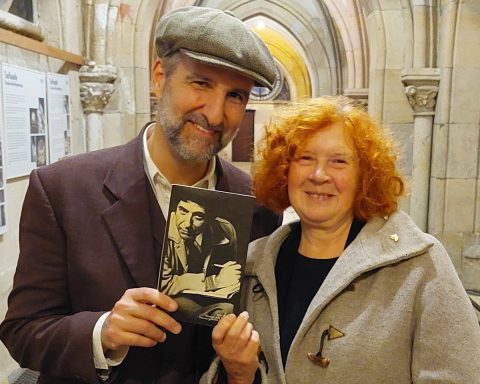

I was reading through some of my stuff over Christmas when I rediscovered this very interesting interview I conducted some time ago on Christianity, with Prof. Robert Inchausti. The Cal Poly lecturer and author has written five books and organized anthologies of the writings of Thomas Merton, a famous Catholic monk and intellectual of the 20th century.

In his 2012 book Subversive Orthodoxy: Outlaws, Revolutionaries, and Other Christians in Disguise, Inchausti contends that “some of the most brilliant and original critics of modernity have been shaped by Christianity,” as Amazon describes. I find our interview relevant for post-Christmas reflections and discussion – since it is the big annual Christian celebration, and Prof. Inchausti offers some unusual conjectures on Christianity and modern thought here.

Felipe Cherubin: Are we really living the greatest revolution in history? The twenty-first century in the context of the globalization phenomenon begins with the attack of September 11, the financial crisis of 2008, the papal resignation of Benedict XVI and popular insurrections in all parts of the world. What is happening and where we are going?

Robert Inchausti: Perhaps the challenge of our time is – as Heidegger put it – that we have forgotten that we have forgotten the question of Being. Only our largely misunderstood artists have remembered to remember! Kafka, Borges, Lispector, Kundera, Warhol and Coltrane – to name a few.

But our cultural institutions – political, educational, religious and scientific – continue to forget our forsaken spiritual context, and so rationalism, ideology, and hierarchy proceed along their merry way as ends in themselves.

This replacement of the system-less-ness of nature with techniques of control renders grace opaque and drives the sacred underground. This has been going on at least since the seventeenth century and has been working its way across continents and cultures, disciplines and traditions one by one. Only recently have we begun the painstaking task of sorting out this confusion of realms. But our progress is uneven, and there is always a time lag behind the perception and the act.

FC: What is to go beyond the position of saying “no” to modernism? You mention Andy Warhol, John Cage, John Coltrane and even Theodor Adorno. These men’s attachment to Christianity causes strangeness and wonder for many people. Could you explain what each has to offer to support your “thesis” of a “Subversive Orthodoxy?”

RI: Andy Warhol took his mother to church and painted religious iconography in the last years of his career. Only after Coltrane found Jesus did he overcome his addictions and compose Love Supreme. Adorno saw the fulfillment of his Negative Dialectics in the messianic light of the last day. Each of these members of the avant garde rediscovered lost truths of Christian Orthodoxy through their own experimental postmodern aesthetic practices. None of them turned religious icons into “idols,” so they were able to help reanimate Orthodoxy.

FC: What do you mean when you report in your book that Christianity is not dead but risen at least five times as Chesterton pointed out? God is frequently proclaimed dead by many contemporary authors, especially for the more radical wing of the neo atheist movement (e.g. Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, Sam Harris, Christopher Hitchens). Is God really dead?

RI: Every time God has “died” it has always been an out-moded concept of God that has died – not God. The tribal God gave way to the sky God who gave way to the universal omnipresent God who gave way to the divine clock maker who gave way to the absent God of existential theism. Of course, this a caricature, but you get my point.

We change, God doesn’t.

The God that is dead today is the metaphysical God-Object, that non literary God born of Cartesian metaphysical and rational polarities. [It is] the God atheists never believed in. That God is dead, but it turns out he never existed, as any Subversive Christian can tell you. The sorry Gods that Dawkins, Dennett, Harris or Hitchens describe rightly deserve our contempt, but they aren’t God.

FC: You place the poet William Blake as a pioneer of a kind of “new wave.” Could you talk a little about the contrast between Blake and Goethe, and the strength of the role that poetry and literature play in the human soul?

RI: I am always surprised when I come across intelligent people who have no serious interest in literature. Some of our brightest modern thinkers – Dewey, Whitehead, Chomsky, and Latour – focus primarily upon the epistemology of science and dismiss fiction as mere fiction. As a result, their works often lack an eschatological dimension or poetic timelessness.

When Blake wrote, “The Vision of Christ that thou dost see,/ Is my vision’s greatest enemy/ Thine is the Friend of all Mankind,/ Mine speaks Parables to the blind,” he was reminding the world that Christianity is first and foremost a prophecy expressed in and through the literary imagination – and hence incompatible with the new materialist theologies and deisms emerging all around him.

Goethe argued in a similar fashion. Faust lost his soul to the power seeking aims of rationalism and method, only to be saved at the last moment by the paradoxes of grace. But to understand such a salvation, one needs to understand the poetic truth and the meaning of mimesis.

Too many moderns suffer from what Roland Barthes called “asymbology” – the inability to think seriously and figuratively at the same time.

FC: Currently, it is not uncommon that some people “smirch” the Beat generation as a decadent movement. You, however, put Jack Kerouac on the other side of the tide. Could you comment on that?

RI: The content of Kerouac’s prose is poetry, and the content of his poetry is the spiritual redemption of experience. His loosely plotted books are not moral tracts – which is the only thing rationalists seem to look for in art. So his critics miss the fact that Kerouac’s novels offer the reader something better and more honest that ethical judgments. They enact human sympathy and direct experience.

When you read Kerouac, you become Kerouac; you see through his eyes, you experience – for perhaps the very first time – the reality of another man’s soul. This is not theology or ideology or even metaphysics, but unmediated intellectual spiritus. The very essence of the poetic imagination and a “cure” for asymbology.

FC: When you talk about the transition from a certain period for Russian cultural legacy, the following question comes to my mind: How on earth was it possible to save all of the best in Russian culture while Russia lost everything in the political dimension?

RI: The British Romantics protested industrialism – and lost. England became the first industrial state. But in the long run, the British romantic poets captured the imagination of the world, and so won spiritually, if not socioeconomically. The Russian Realists of the nineteenth century – Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Chekhov – are more alive today than the communist party congresses that condemned their political backwardness or banned the publication of their books.

The miracle here is merely that the imagination and the spirit seem to be on a different track than that of the material history. But we have a hard time seeing this, just as we have a hard time “seeing” natural selection or the fading away of one eco-system into another over time.

FC: The movement of the neoconservatives with Roger Kimball and the “New Criterion” magazine are very critical of what they consider culturally decadent and degenerate – and it is not unusual that the criticisms come with slander and “ad hominem” arguments. The cases of Kerouac and Michel Foucault are exemplary. At the same time, the neoconservatives place themselves as the strongest advocates of “tradition,” specifically a kind of “ambiguous” Judeo Christian tradition, and often against an “ambiguous” concept of a “Cultural Marxism” tradition. In the end, what tradition are they really defending (and attacking)? Reading your book, it seems to me that they are part of the problem and not a kind of solution (or “saviors”) for civilization.

RI: Franz Kafka once said that the problem with the modern world is that everything goes by false names: “The Communists call themselves revolutionaries, but they are really totalitarians. The Capitalists call themselves free-marketers but they are real monopolists.”

I think this sort of linguistic inversion applies to the contemporary reformers who call themselves “traditionalists.” Their social and economic theories are modern – a mere hundred and fifty years old. They seldom acknowledge this. Indeed, they often render their ideas into ahistorical absolutes and ignore the different cultural contexts that shaped their original meanings and reception.

So although they call themselves traditionalists, they are really “pop culture Christians” reading into the Gospels non-existent antipathy to things like gay marriage and socialized medicine.

FC: It is almost impossible to read your book without taking into account the phenomenon of Messianism. We know that Messianic thought consequences are often catastrophic (totalitarian governments, sects, mass suicides, terrorism, genocides, social segregation, etc.) What drives people to buy messianic ideas in an unhealthy way?

RI: The Messianic idea is an historical rendering of eschatology. That is to say, the Messianic imagination looks at the present in the light of the last days and by so doing makes the sacredness of eternity visible in time. But those more interested in history and power than in eternity or the sacred turn the Messianic promise upside down and seek power in history, using scripture as their guidebook and self-justification.

This perversion of the best is the worst. Why does anyone do it? Perhaps because they lack faith, and so feel they have to take matters into their own hands. Isn’t that the usual self-justification?

FC: The Orlando Sentinel quoted actor Jim Caviezel, who played Jesus in Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, as saying that the role ruined his career – and that yet, he has no regrets and his performance only increased his faith and spirituality. Also Caviezel said Gibson himself warned him that he would never work in Hollywood again after doing the film. Using this episode just as an example, can we affirm that there exists an actual lobby or “oppression” by many kinds of industries against not only Christianity, but also all kinds of “real ” spiritual representations in society and mass media/culture ?

RI: The Passion of the Christ was not a bad film if you take the ideology out of it – something neither its makers nor its critics exactly knew how to do. This explains why Caviezel found himself becoming a more ideologically convinced Christian and a Hollywood exile at the same time. This false conflict, however, was more of a product of the culture wars at the time than any inherent contradiction between religion and art.

The “lobby” that works against Christian art is a mirror image of the “lobby” that puts Christian ideology into art.

They are the same kind of people who see Kerouac as an apostate because they reduce aesthetics to dogmatics. They fail to grasp the way the Gospels unify the subversive with the orthodox, and so they take sides in the rigged political game of left versus right.

Dead Man Walking was a Christian film made by Hollywood darlings, but its Christian spirituality was largely over shadowed by its political correctness! So, unlike Caviezel, Susan Sarandon didn’t have to choose between a lucrative movie career and her religious convictions. She could have her cake and eat it too, because the critics thought her movie was just about Capital Punishment. But it was more than that, better than that. Like The Passion of the Christ, it was ontologically significant – not merely an ethical tract. In both films, God is beyond narrow human conceptions of good and evil, and so [they] assault our moral complacency.

FC: Pope Francis I has shocked not only the Christian world but also the secular world with his attitudes and statements. How do you view the performance of the new Pope? Is he a subversive? Or, in other words, is he the representation of “the ignorant perfection of ordinary people?”

RI: Pope Francis is an Orthodox Subversive, a beautiful example of the ignorant perfection of ordinary people. He is also a literary man, so he understands the irony of being the head of an international organization whose founder was poor, powerless, and excluded. He understands how Jesus and Saint Paul could claim that the highest form of Jewish Orthodoxy comes from its universality and politically subversive elements, just as the Buddha saw through the ethnocentric misreadings of the Vedas.

For some reason, the literary nature of spiritual texts is hard for many of our otherwise best thinkers to grasp. Without the capacity to understand poetry, paradox, literariness, or mimesis, we forget the intimate presence of the sacred and end up trying to systematize the system-less – something nature knows how to avoid. (Hence its capacity to survive us.)

Without imagination, we inevitably turn our icons into idols and miss the point entirely.

FC: Today, we are witnessing around the world various facets of “social activism.” In Brazil, this has grown considerably. However, it appears that many of the activists advocate kind of “nonsense” causes. Many good intentions end up losing themselves in vanity, lack of information, hysterical behavior and histrionics. And, unfortunately, also in unnecessary violence. Is there “unhealthy” social activism? Why do people – often very intelligent – enter in a fetishistic kind of activism, exchanging peaceful dialogue for violence?

RI: The work of René Girard – another literary man who understands the paradoxes in scripture and dynamics of mimetic desire – provides the definitive answer to this question. The Christian Gospels demonstrate that God is on the side of the scapegoat – not on the side of those who sacrifice scapegoats! He prefers the victim to the lynch mob! This is the great truth that liberates us from the lie of ethnocentrism and the false pride of religious and political triumphalism.

It also frees us from the universal bane of coveting our neighbors’ riches and/or Being – if we take it to heart. You can tell “unhealthy” social activism by its tendency to scapegoat. Non-violence is simply the principle that no other person should have to physically suffer for our socially disruptive acts of moral righteousness. We alone pay the price and take responsibility for the consequences.

FC: As a man and scholar, what is your definition of intelligence? And most importantly: what is your definition of redemption?

RI: To be intelligent is to be sensitive to reality. And for me, redemption is a word for grace – received and acknowledged. But it is not a simple as it sounds, since grace operates in many forms on many levels.