Often, when idly thinking, I’m surprised by random details of what my dad used to be before his death. Surprising is also how many of those memories are connected to little physical traits rather than emotions per se. Gestures rather than grand abstract themes.

The casual, confident way he used to hold the steering wheel. How his deep, warm voice sounded greeting me on the phone. Smacking his lips and letting the foam stay on them when drinking a beer he liked. A mole on the side of his face, and the little holes where he had the moles removed from his nose. His silver watch too tight around his thick, brown wrist.

The wispy black hair just starting to fall off and lingering on the white pillow of his hospital bed, after his heart had stopped beating.

And then, ashes.

No more hands to hold, mouth to speak – his thinned but still tanned arms and torso turned into a fine gray powder, as if an evil witch had waved a wand.

The witch at the funeral home handed me a plain, small cardboard box, of which I can remember every detail. The beige color, and how the box still felt hot resting on my palms. The fine gray powder inside a thick plastic bag. That was my dad.

We scattered him to the sea and wind that same evening, instead of keeping him in an urn.

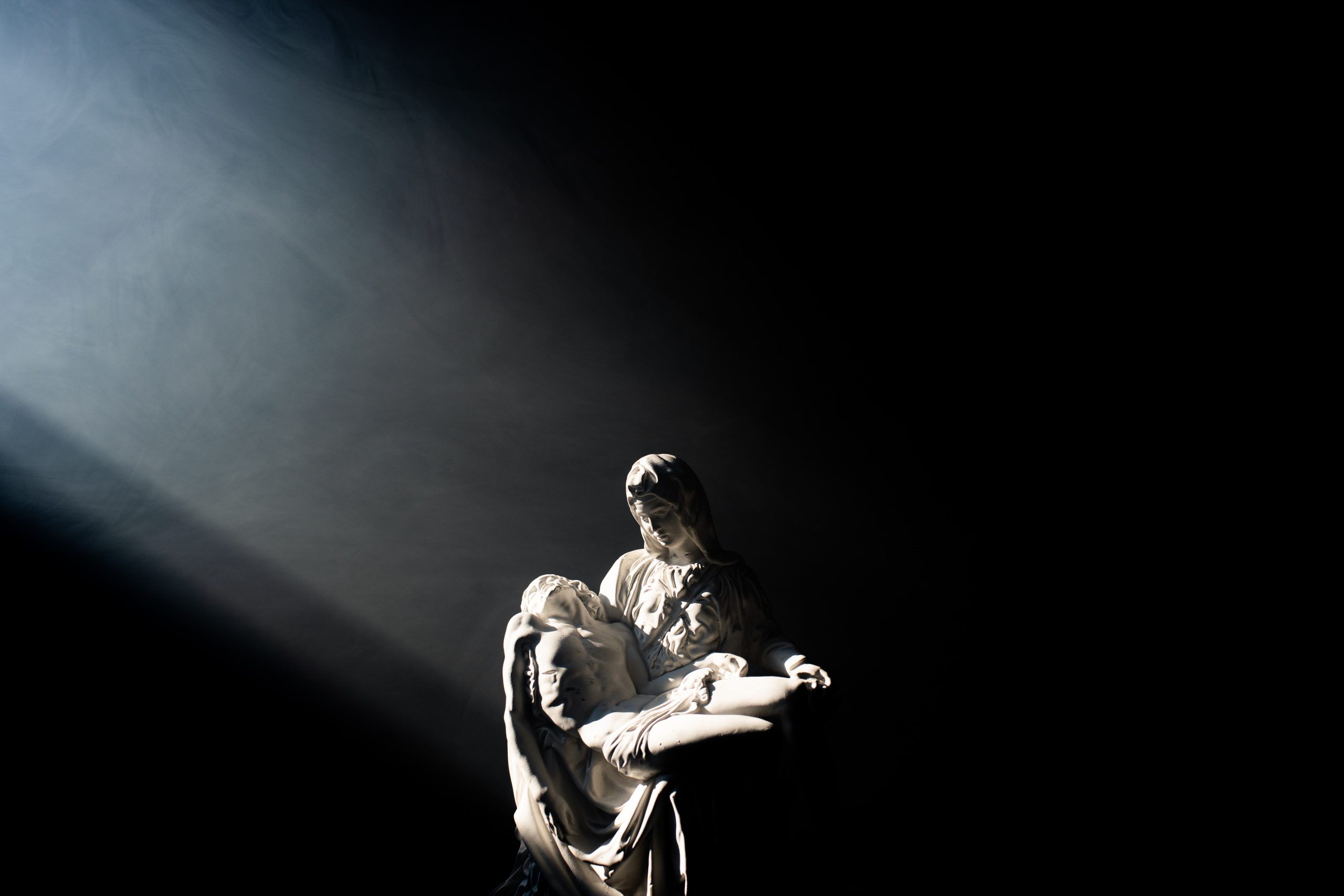

Now I sometimes wish there was a grave I could go to, even though I know he doesn’t have ears to hear us anymore. I’d pray to him, but I don’t believe he can perceive it.

If there is such thing as life after death, I don’t think we get to retain our physical capabilities.

If we do communicate then, we probably do so in a way humans cannot pick up, however psychic some may claim to be.

I reckon that may also be why we haven’t been able to confirm the existence of aliens. Time, movement, weight for them cannot possibly mean the same thing as it does for us, unless they live on a planet under identical conditions as the Earth and solar system, and perceive it exactly the same way we do.

Maybe we just can’t perceive them, and they can’t perceive us. Imagine, then, being dead… weightless, timeless…

My dad, now a collection of other people’s memories, would’ve turned 76 today.

Exactly a year ago, we still celebrated with him. Happily drinking his beer and finishing a big plate, surely he couldn’t have imagined it would be his last birthday, that he’d be a fine gray powder a mere 13 weeks later. Often none of us can imagine.

It sneaks up on us, just like that.

But somehow I just happened to be there for the last three months of his life, having lived abroad for several years. I can’t explain how.

Meanwhile, scientists can’t explain why some form of awareness seems to survive after someone has been declared dead, based on accounts of those who were eventually revived.

I wonder if my dad remained aware, at least for some seconds after the nurse told us, “he’s gone.” But I won’t pretend I know the answer, however unsettled my skepticism makes me feel.

Everything we believe to be real about death probably isn’t, except for the ceasing of bodily functions. Death, beyond the physical, isn’t something our limited human minds can possibly comprehend.

In other words: I don’t mean to disrespect anyone’s religion, but I think it’s likely that every interpretation we’ve managed to come up with is a mere figment.

We’re raised to believe or later grow to believe different versions of the story (or myth) of what happens, when no one alive can know for sure. Questioning what we’re told is not an easy journey, and one that can leave one feeling isolated and vulnerable. But I’m trying to learn to accept such a state, to give up searching for a satisfactory explanation when I keep going back to the idea that there can be none.

Call it my own version of faith. I’m not looking for a label.

One of my favorite articles about dealing with a father’s death (in “Ask Polly”) advises the daughter against trying to fill the void from his departure.

Writes Polly, who lost her father two decades ago and is still reeling from it:

“If I turn my back on how important he is, I block my path to joy. I block my ability to bring joy to other people. He is a vital part of my life. And even the sadness I feel about losing him is vital. It makes every color brighter, it makes every single moment of happiness – or longing, or satisfaction, or grace, or melancholy – more real, more palpable, more complete.”

Besides missing my dad daily, I am now, having seen death, a lot more fully aware of my own mortality – and indeed, of many passing moments.

I can now wish for nothing more than being able to embrace the great unknown. Than being able to live life without (so much) fear and with (more) appreciation, realizing that dying is as natural as living.

That is just what my dad seemed to realize in his final moments of confirmed lucidity.

He resisted sedatives, made light of his deathbed visions, and still managed to joke around – right up until his voice and motor functions failed. He held my hand, calmly, until he had to let go.

And that is perhaps the best parting gift he could’ve given me.