By now, most of us are probably aware of the miserable conditions in Asian textile factories. Hidden messages sewn into the fabric of clothes made for companies such as Primark or Zara keep calling our attention to why the clothes we buy have become so cheap. Nevertheless, if you think that the problem is limited to Bangladesh or Thailand, you may be gravely mistaken. Indeed, a few weeks ago, Serbian activist Bojana Tamindžija came to Leipzig to talk about production and the grossly substandard wages and work conditions in shoe and garment factories in South Eastern Europe.

I found her talk – which focused on Serbian factories – to be an eye-opener.

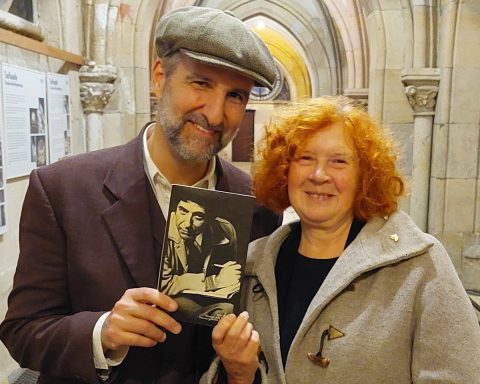

I asked her for an interview to help spread her message. Here’s what she had to say.

Leipzig Glocal: Bojana, you have recently visited Leipzig to talk about the attempts of the Clean Clothes Campaign (CCC) to draw attention to the production conditions in Serbian garment and shoe factories. Most recently, CCC has produced a report on Serbia, for which you are the primary author. Could you tell us what you found?

Bojana Tamindžija: Primarily we found out that many world-famous garment and shoe brands produce in Serbia. In some cases, this information is easily available, when factories publicly announce which brands are among their buyers. However, often this data is hidden because some brands wish to hide the working conditions under which their commodities are produced. They may also want to conceal the salaries of the Serbian workers, as the shoes and clothes they produce cheaply in Serbia are often sold expensively in the Western countries.

Nearly all production facilities exhibit extremely poor working conditions and very low wages.

LG: Why does Serbia represent such an attractive production location for the textile industry? What incentives are there for these companies to move to Serbia?

BT: After a transition from the planned economy to the market economy, Serbia and the other countries in the region were left without their own industry and with a vast amount of unemployed people. Without its own resources to revitalize the domestic economy, Serbia functioned as a foreign capital fertilization service by offering a cheap, well-educated and well-trained labor force. This is the main reason why it is lucrative for foreign companies to operate in Serbia. Brochures that invite companies from the textile industry to start their production here say that savings on unit per labor costs are over 80% compared to EU countries. Apart from that, Serbia offers a wide range of tax relief and subsidies.

LG: Do you think Serbia as a country has at all benefited from the construction of garments factories?

BT: Definitely not. Serbia is caught in a vicious circle of debt to foreign creditors and dependency on foreign investment. This occurs at the expense of a low-paid, disfranchised and hungry population. If a company receives 9,000 euros of state subsidies per worker, this means that this worker is essentially paid by tax money rather than by the company for the next three years. Moreover, it is often the case that the land and basic infrastructure are offered to the company for free or at a very low price, along with corporate income tax relief and payroll tax incentives. The companies which operate in the so called free zones have even more privileges.

LG: As you said earlier, the wages of Serbian workers are very low, especially by German standards. How does the cost of living in Serbia compare with Western Europe?

BT: Compared to the Western European countries, the cost of living in Serbia is indeed slightly lower. However, in order to create a more realistic picture of how low the wages of the textile industry’s workers actually are, one should compare them with the living costs in Serbia. Most workers receive the official minimum wage, which is just above 200 euros. This stands in contrast to the living wage of Serbia, which is well above 800 euros. The living wage refers to the amount of money required to live reasonably comfortably. This basically means that the wage cannot even cover food expenses, meaning that it is not even sufficient for physiological survival.

LG: Do you think men and women are equally affected by the dire working conditions you speak of?

BT: Large parts of the textile industry traditionally employ a female work force. At the same time, the textile industry is one of the lowest paid sectors of the economy. This suggests that female labor is seen as less valuable. Because of the low wages,many female workers are forced to have additional jobs. This makes women’s positions especially vulnerable, as these jobs are carried out in addition to domestic work.

LG: Historically, strikes and union action have been used to improve working conditions and salaries. Have workers in the textile industry been going on strike, and with what results?

BT: Last year, there were numerous strikes in Serbia, and many of them happened within the textile industry. Even though there are no formal barriers for the foundation of trade unions in foreign factories, unions are dealing with a lot of obstacles and worsening circumstances when trying to operate. On the other hand, workers who revolt against the working conditions are faced with the threat of dismissal and different kinds of harassment. Because of their existential vulnerability and the limited ability to organize around the trade unions, workers remain in a delicate position.

LG: Do you think that the story you are telling pertains only to Serbia or to the Balkans in general?

BT: When it comes to the textile industry, an identical situation exists in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Macedonia and Albania. In general, the whole region has become a reservoir of a low-paid workers that the big players use for profit. On the other hand, the regional governments have further limited labor rights, offering subsidies and other conveniences in order to attract foreign companies and to solve the problem of unemployment. This is something that is often referred to as a “race to the bottom,” where the main imperative is to increase the profit by finding different ways to reduce labor costs over and over again.

LG: Has EU membership made any difference for people employed by the clothing industry?

BT: There are definitely huge differences in working conditions and wages between EU countries and the rest of Europe. However, the European Union is not a monolithic formation; for example, the wages and working conditions of Romanian and Ukrainian workers in the textile industry are closer to the wages of workers in the Western Balkans.

On the other hand, the textile industry’s workers in the Western European countries have salaries that are up to five times higher than those of workers in Serbia in the same positions.

LG: What do you think that Western European consumers can do to make a difference?

BT: Consumers are not responsible for the current situation, but policy makers are. If we want to make a difference, we need to point our fingers at policy makers and fashion brands. However, consumers may help accelerate change. I do not believe that anyone would like to buy a product if they know that the workers who produced it have wages which are so low that they cannot even live from them, that their basic labor rights are constantly diminished, that they are not allowed to go to the toilet, that they are not allowed to get their annual vacation, that they are often forced to work overtime without payment, and that they do not have adequate protection at work.

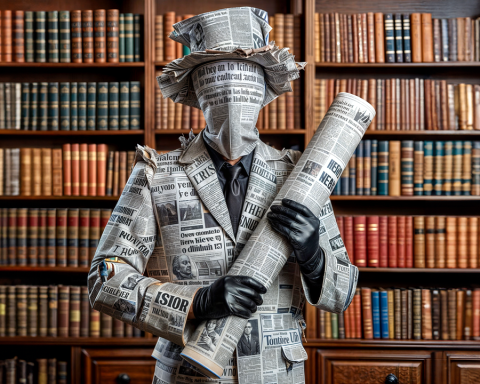

Cover shot: Image used to illustrate CCC research on garment factories. (Photo credit: Yevgenia Belorusets)