The results of the European elections have followed and also caused political turmoil in much of Europe.

New elections loom in Austria and Greece. In Poland, Italy and France, nationalists have become the strongest political power. In the UK, Theresa May has finally announced her resignation.

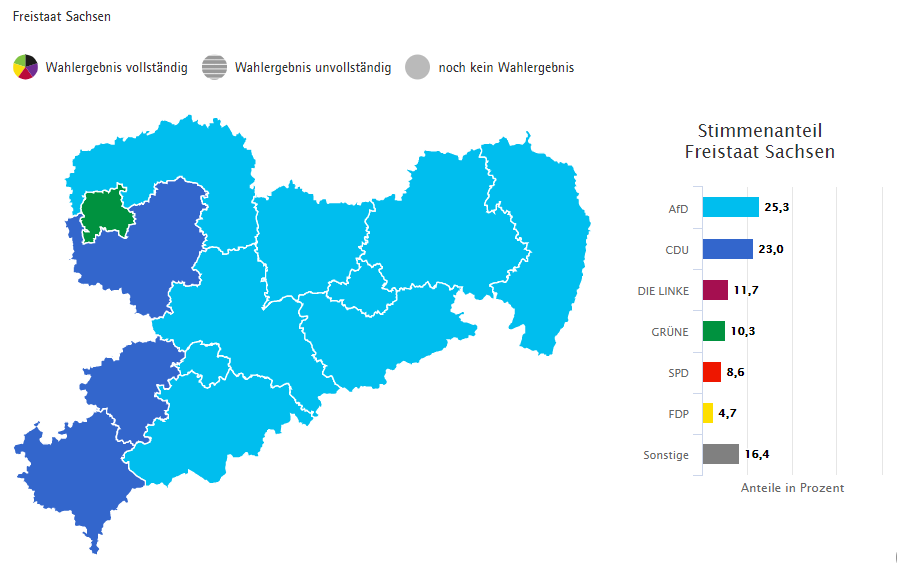

From the German point of view, the results are slightly less spectacular than many had anticipated. Nevertheless, in Saxony, the AfD achieved more than 25%, and more than 20% both in Thuringia and Saxony-Anhalt.

What the European elections do highlight is a number of divisions within German society.

They are likely to contribute to an increasing polarization of politics within the coming years, rather than just being a passing phase or a thing of the past.

The first is the division between old voters and young voters.

In Germany, 34% of those below the age of 25 gave their vote to the Greens, as opposed to 12% for the CDU, 8% for the SPD, and 8% for DIE LINKE. The AfD only received 5% of this group’s voting share, but twice as much from those above 45 years old. Among those older than 60, the CDU received about 40% of votes.

This development underlines how Europe’s changing demography has an impact on democracy. Low birth rates and aging populations throughout the EU cause an overrepresentation of conservative parties. Moreover (and, of course, I am speculating here), perhaps older people are less concerned with the problems of the future, as they are less likely to experience them within their lifetimes.

Another division is the split between rural and urban areas.

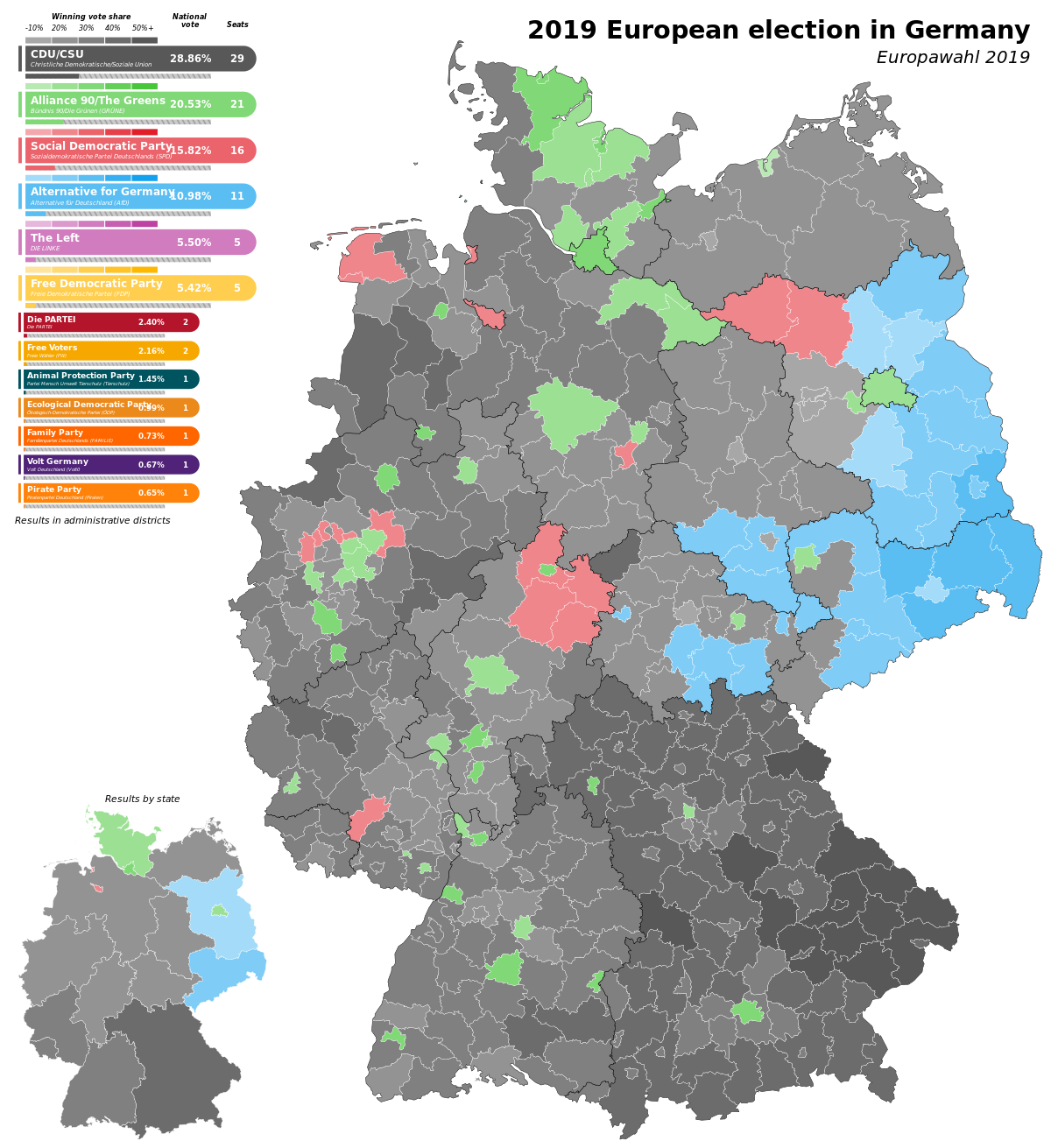

The Greens became the largest party in all the largest German cities: Berlin, Hamburg, Munich, Cologne, Stuttgart, Dusseldorf, Dortmund, and Leipzig. In rural areas, however, the Greens haven’t performed anywhere near as well.

In my own district of Schleußig, the Greens received 34.2% of the votes, as opposed to around 10% in Leipzig’s rural neighborhoods (e.g. Seehausen, Liebertwolkwitz). In some rural areas of Leipzig, the AfD received nearly 30%, compared with 5.6% in Südvorstadt.

I believe that this increasing division is due to two major factors.

Firstly, the lack of job opportunities in rural areas is pushing young people towards the major cities. The older people who remain are more likely to vote for the right.

Secondly, many of the current political debates ignore the concerns of rural populations. High rents in cities are of no consequence for rural areas. The anti-car rhetoric employed by many supporters of the Greens, however, is a slap in the face for people in rural areas who depend on cars for transportation. Shutting down lignite production will cost jobs and end century-old traditions, with no adequate replacement in sight.

Country dwellers wonder why so much money is available for refugees, while rural schools, bakeries and pubs are shutting down.

A third division that became even more apparent through these European elections is the one between east and west Germany.

If you look at a map of the AfD’s strongest voting districts, you look at a map of the former GDR. The same applies to the map of DIE LINKE’s strongest districts. The strongest districts of the Greens are roughly equivalent to the territory of the former West Germany.

One of the reasons for that is certainly the discourse surrounding east Germany that has been employed by west German media. East Germans are often portrayed as racist naysayers who are unable to look at themselves as the cause of their problems. The history of the GDR is often reduced to the Stasi. The two parties that picked up on these perceptions are DIE LINKE and the AfD, with the latter being far more successful.

By Erinthecute – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

The three major divisions I mentioned here have different historical and demographic origins.

They cannot simply be cancelled out by political speech acts or a change in party leadership. Nevertheless, I do believe it is time for parties to find allies beyond the traditional political spectrum.

The age of mass movements appears to have ended. Coalition governments have become the norm across Europe, and people increasingly vote for parties because of their candidates and the issues they represent. Class and religion, which have historically played a huge role in political affiliation, are becoming less important.

Parties increasingly represent issues and interest groups, which means that no single party will be able to form a government. One way to overcome divisions may just be to include more political forces in the exercise of government. It has always been one of the strengths of the European Parliament that there are no official coalitions. A majority has to be found anew on every single issue.

Perhaps the EU model of government is the way forward for regional and national governments as well.