Being from the presidential system known as Brazil, we are hard-wired to feel strongly about the president. He – as all but one have been white men, and the one woman was impeached – personifies the State. Populist times turn him into a myth who carries all the (mis)fortune of the Nation on his shoulders. In their fanaticism, many Brazilians treat him like either a god or a demon. It happened to Lula da Silva (from the left-leaning Workers’ Party), and is now happening to his foil Jair Bolsonaro (from the far-right Social Liberal Party).

Admittedly, the mere mention of the name Bolsonaro makes my guts churn. This man and his Cabinet represent the bigoted authoritarianism, militia mentality and ignorance that keep kicking Brazil – until recently an “emerging power” – on the back of the legs and back onto the ground. Like his buddy Donald Trump in the US, Bolsonaro and his camp clawed their way to the top by preying on people’s insecurities and in some cases latent racism, sexism and homophobia. Similarly to the US and Germany, Brazilian right-wingers dump their blame onto “the other” for the quagmire this unequal, cut-throat system has trapped them in. Instead of examining one’s own positioning in such a system, it’s much easier to blame a socially vulnerable or contrary person or group, and equally to deposit all hopes or frustrations onto a powerful one (the president and his lackeys).

It was with this context in mind that I visited the exhibit “Die Macht der Vervielfältigung” in Spinnerei’s Halle 12 – because the description I was emailed mentioned Bolsonaro:

“With ‘The Power of Reproduction,’ the Goethe-Institut Porto Alegre will be showing 14 German and Brazilian artists in a joint exhibition at [Leipzig’s] Spinnerei. [The Brazilian city of] Porto Alegre is well-known for its tradition of printmaking and the associated attitude of producing art for the small budget, making it accessible to a broader segment of the population. The exhibit is especially relevant in light of current events in Brazil, with the right-wing populist President Jair Bolsonaro dissolving the Ministry of Culture. The need for critical voices among artists, especially in a socially embedded genre such as graphics, is clearly demonstrated.”

Ah, yes, culture. The Bolsonaro people don’t like that so much. Culture is dangerous. Thinking they are defying the establishment, the automatons repeat the global right-wing accusations of “mimimi,” “fake news” and “climate hoax.” They preach that Brazil has been taken over by a Communist conspiracy, further established by the Workers’ Party and its social programs, and which Bolsonaro (dubbed “The Myth”) shall uproot with holy water (or shackles, or guns, or little spies in classrooms). These are terrifying echoes of the discourse that sought to justify the 1964 military coup d’etat in Brazil, some of it making its way into policy as we speak.

According to this group of voters, such Communist conspiracy is in cahoots with deconstructivists to subvert and destabilize society by challenging hallowed definitions like gender (and by extension gender roles and the nuclear family) as social constructs. Some have even gone so far as equating Socialism with Nazism (National Socialism), which concerned the German Embassy in Brazil so much that it launched a social media campaign to try to debunk the myth in the lead-up to last year’s presidential elections. So maybe the Goethe-Institut would promote some clear debunking as well.

Walking into Spinnerei’s WERKSCHAU, I fully expected to see Bolsonaro’s effigy in all manners of artistic defacing, like I once saw Francis Fukuyama’s when browsing the halls of the old cotton mill in 2015. (You know, strong feelings and all.) Instead, I only caught Bolsonaro’s silhouette, so to speak, lurking around the political art. Present and almost palpable, but not obvious, kind of like how artists protested during the Brazilian right-wing dictatorship in 1964-85. Interestingly, there were direct connections to that period in some of the work on display.

I grabbed a pamphlet of “Bem-vindo, presidente!” (“Welcome, President!”) by Brazilian artist Rafael Pagatini, so I could refer to it later.

Produced in 2015-16, it was prescient of the current situation and also probably referring to the sentiments of the time, when a group of deeply disgruntled and disturbed Brazilians called for a return of the right-wing military rule. Buoyed by an epidemic of social and traditional media propaganda on his behalf, Bolsonaro was elected president in 2018, being known to support the bygone dictatorship. His support of commodity-extracting industries in Brazil, in detriment of the Amazon and environment in general, is also notorious – though not unique in contemporary Brazilian politics, and definitely a mark of the dictatorship in the 60s-80s. Perhaps the artist’s piece, a chronicle of bits of propaganda laid across one wall, means to express that history repeats itself, or that it only appears to change as a new president comes to power.

The installation, says Pagatini’s website, is “based on the cataloging of ads from companies from the 60s, 70s and 80s, published in the newspaper A Gazeta, in circulation in the [Brazilian] city of Vitória. [They] were based on the visit of the military presidents… for the inauguration of [large extractive projects]. The work addresses the modernizing discourse in Brazil throughout the military regime and its alliances of power in the press. [The piece] seeks to point out the relationship between military and private initiative; therefore, it presents the newspaper as a public space for discussion and ideological arm of the regime.”

Another one of the exhibit’s prominent political works, perhaps a tad more optimistic, hung towards the back of the hall. By German artist Thomas Kilpper, it’s entitled “another world is necessary – or: don’t think about the crisis – fight!”

In the same year the mural is from, 2016, Workers’ Party President Dilma Rousseff was impeached. It happened amid a shakeup that led to the arrest of Lula and many other political and corporate power players in Brazil, on corruption charges. Bolsonaro’s election as a hardliner on violent crime, corruption and what some saw as a crisis of morality in society was the culmination of such a shakeup, although his own record of cleanliness and non-violence has now come into question.

Kilpper’s piece has a two-pronged approach: It shows a few characters and entities important or symbolic in Brazilian political history, particularly relating to the dictatorship. Others are connected to Porto Alegre or the specific site where the artist’s mural was produced. Some fall into both categories, based on the mini-biographies a plaque nearby provides on them. For instance, the depicted Maria Thereza Goulart was the First Lady of Brazil when the military overthrew the democratic regime in 1964, and she had also attended school in Porto Alegre as a teenager.

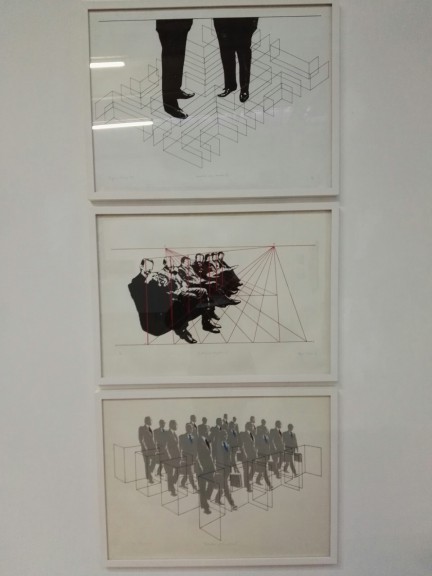

Then there’s the work of Regina Silveira, focused on the executive and the military both in societal and environmental terms.

One series produced in 1974-76 shows “the [male] executive” – which can mean both a businessman and the executive branch of government – in symmetrical positions or military-like formation. The figures look like clones of each other, all white (or colorless) men in black suits. They are prisoners of their own societal structure.

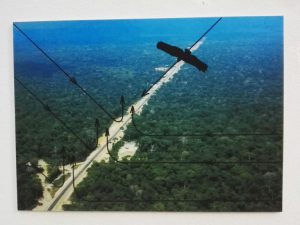

Another work by Silveira depicts the Trans-Amazonian Highway with a black bird flying over it. The piece is located closer to the entrance of the exhibit. It is from 2018, while the highway was a project introduced in 1972 by the Brazilian military dictatorship.

The regime’s idea was to cut and pave a huge deforesting swath through the Amazon, to connect the northern states with the rest of Brazil and the neighboring countries. Due to financial and logistical difficulties, the road was never fully paved or finished.

One of the current priorities of the Bolsonaro government is to privatize transportation infrastructure and make it easier for commodities to be exported. This includes the Trans-Amazonian Highway.

The WERKSCHAU exhibit is not all about political issues, though. There’s some more abstract work and even a whole wall of augmented reality, where you must use special glasses to see the figures jump out at you. So even if you don’t feel strongly about Brazilian presidents, you’re bound to find something of interest.

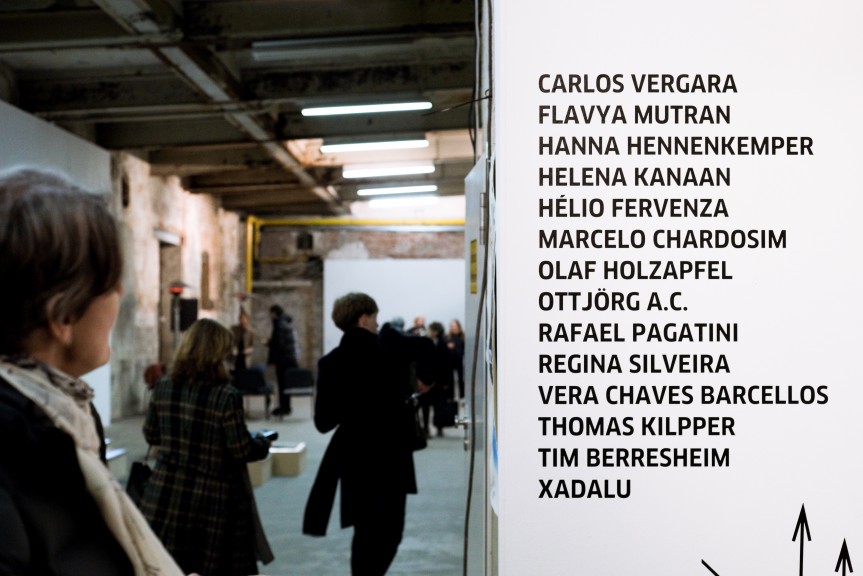

Die Macht der Vervielfältigung – Power of Reproduction

28 Feb – 23 March 2019

Leipziger Baumwollspinnerei Halle 12, Spinnereistraße 7, 04179 Leipzig

Curator: Gregor Jansen

Artist lineup:

Vera Chaves Barcello, Hanna Hennenkemper, Flavya Mutran, Carlos Vergara, Tim Berresheim, Olaf Holzapfel, Ottjorg A.C., XADALU, Marcelo Chardosim, Helena Canaan, Rafael Pagatini, Hélio Fervenza, Thomas Kilpper and Regina Silveira.

![Wine & Paint event on 9 Nov. 2024 at Felix Restaurant, Leipzig. Photo: Florian Reime (@reime.visuals] / Wine & Paint Leipzig](https://leipglo.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/pixelcut-export-e1733056018933-480x384.jpeg)