LeipGlo column: Literary Parlor

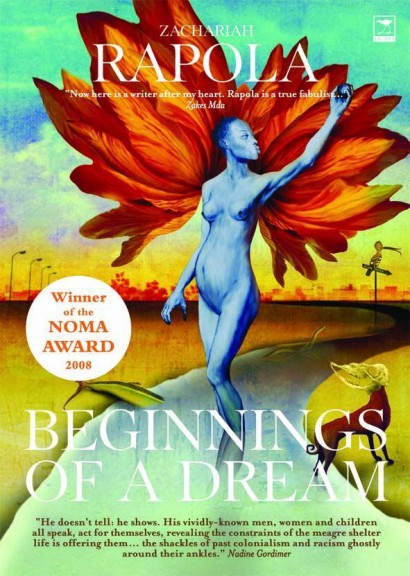

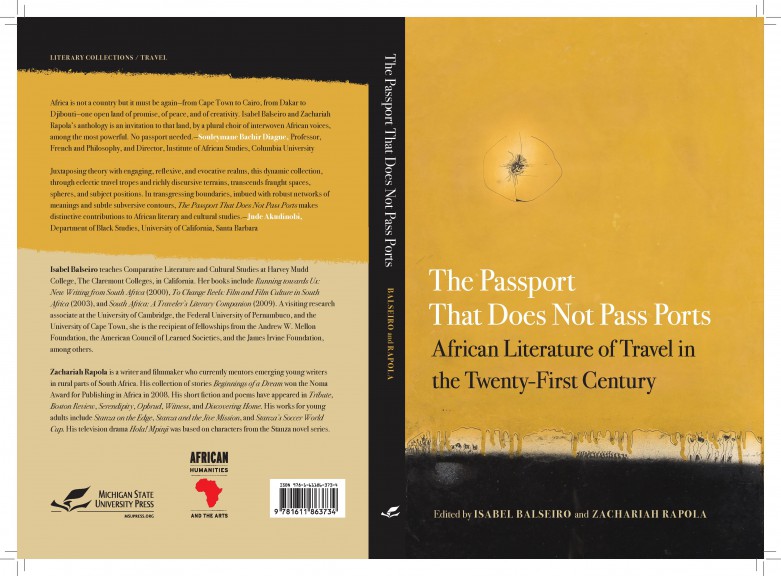

The Literary Parlor is a place where we invite internationally renowned authors to share some of their insights, dig into their craft and reveal their secrets to a successful writing career. In our first Literary Parlor in the New Year, we got to talk with South African author Zachariah Rapola. His most recent publications include his collection of short stories Beginnings of a Dream as well as the South African poetry anthology The Passport That Does Not Pass Ports: African Literature of Travel in the Twenty-First Century, which he co-edited.

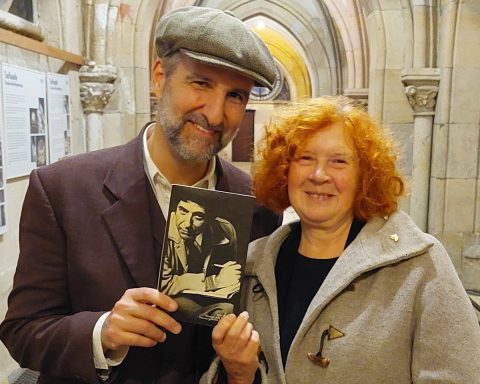

Interview by Svetlana Lavochkina

In what ways did your homeland shape you as a writer?

My writing was in a way shaped by two influences. The first was the folk-tale tradition I grew up listening to narrated by my mother – she was a gifted story teller. Many grandmothers regaled their grandchildren with the same stories. In my case, the absence of a grandmother did not deny me that privilege. My mother did not confine herself to folk tales but also had a great reservoir of oral history episodes concerning exploits of our tribe’s founding queen, Mamahlola, who, legend has, had powers to bring rain. A gift shared by the neighbouring Balobedu tribe ruler, Queen Modjadji – the Rainmaker.

These oral stories helped preserve the history of the tribe, how it battled with not only the invading and land-grabbing Boers but also marauding bands of Ndebele warriors looking for new territories to settle after fleeing from Zululand during the Shaka wars, mainly known as Difaqane.

I have been able to re-tell some of those stories in prose and others in short film, while for many more I still have to figure out the best medium.

Second, the formal education system added to and further consolidated my appreciation of story-telling by introducing me to great Sepedi writers like O. K. Matsepe. Matsepe’s writing has been classified by some as magical realism, and it clearly derives from oral history and traditional story-telling.

I would say that my short-story anthology, Beginnings of a Dream, owes its genesis to the above two influences.

It also greatly benefited from time spent with a couple of elderly people during the writing phase, both as consultants and mentors. And, though much later, I was privileged to be mentored by the great writers Professor Eskiaskia Mphahlele, Nadine Gordimer and Lionel Abrahams.

At the onset of your creative career, you participated in the renowned Iowa Writing Program, something many aspiring artists dream of. Would your creative output look different now had you not enjoyed its benefits?

As you rightly point out, participating in the Iowa Writers Program is the dream of many aspiring writers, and for me it was a great privilege and honour to participate. To be honest, it was also a bit intimidating to interact and rub shoulders with some of the best and top writers from around the world.

I recall that most of those writers (including my dorm mate, from Nigeria) had no less than five publications under their names; one from Northern Africa over twenty. All those wonderful talents as well as the IWP staff welcomed and embraced me warmly. Naturally, this experience motivated me to aspire to quality output.

Also, it was a first experience for me to meet and interact with writers from countries like Russia and Vietnam. More than any other country, coming into contact with somebody from Russia had sentimental values given my great admiration for Russian writers like Tolstoy, Pasternak, Chekhov, Nabokov and Shoklokhlov, and poets like Blok and Mayakovski.

Your prose is sinewy, lean and full of stamina; a marathon-runner metaphor comes to my mind. What is your own perception of your style? Have you ever, albeit subconsciously, tried to emulate your literary idols?

Like many writers, I have been shaped and influenced in my writing by many other writers. The struggle has been to find, amidst all that influence, a voice that amplifies the unique inner voice I believe each of us is born and endowed with. Expressing oneself in that unique voice that distinguishes one from other writers can be a challenge.

My idols vary, and some belong to different poles. I admire Latin American favourites like Fueontes, Vargas Llosa, Allende, García Máarquez etc., who represent magical realism, and people like Okri and Matsepe, who are distinctly influenced by the oral telling of folk stories. Matsepe, one of the pioneering and most revered Sepedi writers, represents my mother tongue as well as personal and cultural identity, whereas Okri represents the worldly outlook and view, Sepedi, resides. Also aware that Okri has been labelled as over elaborative and exuberate by others. The tapestry he is capable of weaving with words is magical. He and Matsepe are aligned in a way, but sit on opposite sides of linguistic, generational and cultural divides. Sitting on a slightly creative orbit is Kundera, another icon of mine.

Representing the extreme opposite of them all is J. M. Coetzee. Now, if you talk of someone whose writing is extremely economical with words but explosive and impactful in its leanness, there are few who can rival Coetzee. His sparse prose dazzles and awes.

You have embarked on many artistic journeys – film-making, photography, comics. Do you adopt a different creative persona while “traveling,” or do you draw from the same sources that nourish your writing, “translating” them, polyglot-like, into the different languages of those creative media?

The different media you cited have their distinct ethos and interpretative formulations, and I have always found myself forced to adapt accordingly. But even that attempt to adapt is to a large degree impacted, consciously or unconsciously, by the same light, at times humorous tone that underlies most of my writing. Even where I make the deliberate choice to suppress it, it always somehow manages to sneak through, for example by finding humour or lightness in the “darkest” environment.

This “creative persona” is the complete opposite of the person I project, who is more reserved, with a conservative and serious demeanour. This is not to say I take everything lightly, but rather that the “creative persona” tends to like and enjoy expressing and conveying “warmth and tenderness.” I guess this in a way automatically excludes me from writing horror!

My filmmaker icons include John Ford, David Lean, Stanley Kubrick, Majidji Madijidi, Krzysztof Kieślowski and Emir Kuosturnica, just to mention a few. David Lean’s Doctor Zhivago is one of my all-time favourite movies. The romantic genre predominates in the two films I am working on currently, the first a TV movie and the second a dramatic feature. But while those filmmakers represent diverse genres and styles, I draw inspiration from each of them.

With regard to comic books, Garth Ennis and Steve Dillon’s Preacher is an inspiration, particularly with the supernatural themes and influences. To go back to your question about “creative persona,” I would say the Preacher comic book series has similar magical and supernatural influences as some of the writers I admire, specifically biblical influences like in Llosa Vargas Llosa’s epic novel The War of the End of the World, another of my favourite reads.

I did my film studies at a time when black and white stills photography was a mandatory course, and while it might have fallen off my practical list today, it has been handy and most relevant in other story-telling genres I have a passion for: picture-story books, graphic novels and motion animation. I have to admit that some of these ventures have come to fruition while others have remained elusive. This includes an animated TV-series concept that, after frustrating years of struggling to get going, is finally back on track due to recent interest in and support for African animation.

Editing an international anthology of poetry is one of your current missions, Zachariah and it isn’t an easy one. What brought you to the idea of compiling it?

First, I have to admit and put on record that sustainability and saving the environment dictates us to take the online route for most publications. Also, online publications have a lot of benefits; they are affordable and skirt the destructive effects print publications are associated with.

Nonetheless, one also has to admit that print publications have a practical and endearing value as well as durability.

Print publications have a certain intimacy that their electronic counterparts can never possess, that is to me. Imagine sitting next to the fire on a cold winter night, alone or with a loved one, and a hard copy of a Baudelaire’s Fleurs du mal, Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell, or any other poet cradled in your arms? Nothing can ever be as heart-warming and charming as this.

I’ve had my copy of Fleurs du mal for years, and when the fancy takes me, I reach out and wrap my arms around it before settling down to start reading. The intimacy of that experience is unimaginable, warm, tender and intoxicating. And you can do it when wrapped under blankets in bed. Now imagine trying to do the same with an electronic device?

Of course I can do some writing on my tablet, and some limited reading, but it just never reciprocates the warmth I feel when having a hard copy in my arms.

I will give another recent example. A couple of weeks ago I came across a really beautiful poem online. I clicked the “like” button – but the format had some practical limitations. Whereas with a hard copy I would have inserted a page marker or piece of paper so I can easily find the poem when I want to re-read it, here I had to rely on visiting the post again – but given the overwhelming volume of online posts, retracing the post proved almost impossible.

I had to resort to posting a request for help from other social-media users with the hope that someone might have read/seen the poem and responded with admiration like I did. But it was never to be. While the poet who posted would most probably have the poem on his timeline, for a fan like myself it is lost, leaving me with moments of regrets. What I’m trying to illustrate with this example is the fleeting duration of online contents, specifically poetry posts on social media.

My putting together the anthology is in part a response to that, a desire to see and ensure that good and great poems are preserved and presented in a physically tangible format that is durable and intimate.

Social media is full of the depth and wealth of poetic talent out there. Without doubt some of it endures, but at the same time there are some gems that if not conserved will be bound for obscurity and lost to a wider poetry-appreciating audience/readership. The anthology aspires to go further than literary magazines and journals, two formats more durable than the online format. This does not in any way undermine or diminish the value of any of the formats – online, magazine or journal – as they all serve the promotion of poetry and poets.

Putting together the anthology, with immense help from New Zealand poet Sue Zhu, has broadened the scope of my reading by introducing me to more established as well as newer poets I was otherwise not aware of, or knew very little about. It has been a major journey into the vast universe of poetry. And looking back to when I started, I can safely say that I have grown immensely from the experience.

For me, responsibility and challenges also grew as I moved from the local to the international arena.

After serving on editorial boards of two national literary journals, running and leading writers’ workshops, I would say putting together the anthology has been like a baptism of fire – an exciting and challenging experience, but with lots of gratifying moments. Like getting to share with South African readers works of some of the talented poets from across the world, and in the same instance having to with the world works of a couple of South African poets, including one extremely talented poet who, on two separate occasions, relegated me to runner-up in national poetry competitions!

I might be over-ambitious, but my desire is to see the wonderful works of all these great poets endure and lodge themselves in the hearts of many readers around the world.

As much as Baudelaire’s Fleurs du mal occupies a special place on my bookshelves, alongside other treasured books, I hope and aspire to see the anthology, Poets and Place: Global Poetry 2021, occupy privileged spaces in the hearts, intellects and home libraries of many readers.

Similarly, my Shakespeare hard-copy collections are as valuable today as they were those many years ago when I bought them. This might sound corny, but a man or woman’s hard-copy library collection volume is the mark priceless wealth he or she possesses.

To conclude, putting together the anthology allowed me to resume the promotion of works by South African poets using online platforms I engaged in a while back.

The focus has broadened now with diverse poets from around the world profiled through the Poets and Places social media series. This of course runs against what I said earlier about the short lifespan of online media, but to contradict myself I would say online and social media have proved to be ideal, easily accessible vehicles to make poets known to a wider audience and readership.

![Wine & Paint event on 9 Nov. 2024 at Felix Restaurant, Leipzig. Photo: Florian Reime (@reime.visuals] / Wine & Paint Leipzig](https://leipglo.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/pixelcut-export-e1733056018933-480x384.jpeg)