Editor’s note: The idea for this column, which debuted two Saturdays ago, is for people to share their transnational cultural experiences – a past and present involving personal relationships where our sense of belonging, country and background intersect with another, or multiple others, in deeply personal ways that imprint feelings and memories and shape us and change us in some important way. If you’d like to share your own story with us as a guest columnist, please write us at newswriterana@gmail.com.

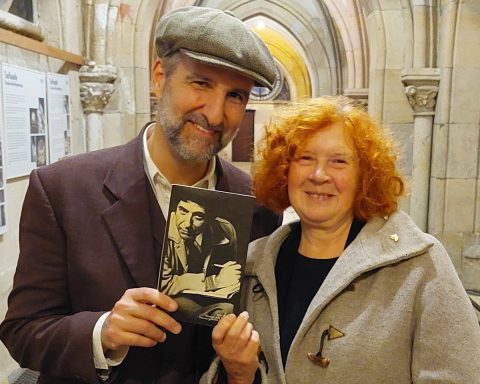

The column has debuted with a five-part series written by German novelist and Leipzig Writer member Diana Feuerbach. Today, in Part III of “Thank you for your letter,” Diana talks about what it was like to be a school pupil learning about the Soviet Union and its “sacred forefathers” in GDR times, adding in little acts of rebelliousness committed by herself and her family – the amount of detail she remembers is quite impressive, and she retells it with wit, irreverence and also poignancy. The series will continue to run every Saturday for the next three weeks.

“Thank you for your letter,” Part III: Lenin goes Punk

By Diana Feuerbach

At school I kept quiet about Lake Baikal and the cardigan. Personal relations with Soviet citizens were nothing to brag about, not even in Russian class. After spending a couple of years with a teacher who was a bipolar madman—our command of the language reflected his lunacy—we eventually got a replacement. Our new teacher’s first name was Olga, with a German last name. The first immigrant I laid eyes on, Olga spoke with an accent. She liked our class, even though we were one of the school’s rowdiest. One day, she made us laugh like crazy by screening a training film starring real Russians. The film was set in a Moscow neighborhood of high-rise plattenbauten. It was winter. The protagonists were wearing the most ludicrous felt hats we’d ever seen. Of their dialogue, we caught nothing but the word voksal—meaning train station. If you say you “understand only Bahnhof” in German, it means it’s all Greek to you. Ashamed of our inability, we resolved to making all the more fun of the Russian felt hats. Falling over with laughter, we even infected our teacher. Olga started laughing with us… a behavior I construed as an act of treason against her people, or at least against her teaching materials.

8 in. x 6 ¾ in. x 5 ¾ in. (20 cm x 17 cm x 14.5 cm). East Germany – Sculptures. Wende Museum, CA, USA. http://www.wendemuseum.org/collections/vandalized-lenin-bust

In history class, I single-handedly denigrated the Soviet Union. We were sitting with our textbooks open. I felt bored. There was a photo of Lenin on the page. With my ballpoint pen, I drew Lenin an earring and a Mohican haircut. The teacher saw it and made me stay after class. From his hoarsely uttered questions I gathered that I was in deep trouble. Forty years earlier in Thuringia, a schoolgirl had adorned a portrait of Stalin with her lipstick. Erika Riemann spent the rest of her youth in Soviet prison camps. I didn’t know about Erika’s fate and I don’t think my teacher did either. Lucky for us, the Stalin era was over. But for all that, turning Lenin into a punk was still a big deal. I played dumb; that was wise. Had I told the teacher that his lessons bored me because they never included history’s interesting details, my parents would have been the ones in trouble, with the school’s principal and some grim comrades from the Stasi paying them a visit. Among other sensitive truths, my dad had told me that Lenin left his Zurich exile in 1917 with the help of the Germans, rolling back home to Mother Russia in a sealed train compartment.

I didn’t say a word. At school, it was always best to keep your knowledge to yourself. At home in our flat on the sixth floor, dad continued to teach me alternative history. ”The Russians are the biggest landgrabbers of all time“, he liked to conclude after studying his history atlas tracing the borderlines of European and Asian countries throughout the centuries. What he said scared the hell out of me. After all, I was still corresponding with Genia from Leningrad. We’d recently switched to writing in English. English was really cool. It worked so well I started to get a feel for the girl beyond the lines. What remained of the Russian language in our letters was the greeting, the standard line thanking for the previous letter and the farewell: Tvoya padruga Diana (your friend Diana).

Meanwhile in Moscow, geriatric general secretaries of the Soviet Communist Party had been dropping like flies, forcing us to feign grief at school every time. Finally, a much younger candidate got the job. He seemed fit despite the large birthmark on his head, looking like purple inkblots. I was hoping he’d hold on for a while so I’d be spared the charade of being sad at school. Landgrabbing didn’t enter in any of this, which left me all the more disturbed by an episode that must have played out shortly before the fall of the Iron Curtain, the promise of ”blooming landscapes“ made by chancellor Kohl and the death of the Warsaw Pact.

In our tiny Trabant, my Dad and I are driving to our garden—a property situated on a hill bordering a forest. We come jolting up the dirt road, suddenly facing a Red Army truck. A radar antenna is mounted on its roof, and it’s parked right outside our gate. What’s going on here? We stop the car and get out. I’m afraid, but I walk along with my father. The garden gate has been unhinged. We hear voices. As we enter the property, we see a fire crackling in our grill near the birch trees. The soldiers, maybe half a dozen, are fiddling with mess kits. They ignore us. My Dad tries to be a good sport. I can feel he’s not in the position to kick out these uninvited guests. The radar reception on the hilltop is likely to be pretty good. The soldiers must have gotten hungry and found no better place nearby to cook lunch. That’s his explanation for their make-shift camp. He walks over to our arbor, keys in hand, with me padding shyly behind him. The key gets jammed in the door lock. Someone has messed with the lock trying to break in. Russian thieves?

Dad asks to speak with an officer. He shows him the damage, getting nothing but a dismissive gesture in return. In silent anger he suddenly asks me to talk to the officer: “You’ve been learning Russian for years! Tell him it’s okay if they want to cook here. But they need to tidy up when they’re done and put the gate back.“ That’s easy for him to say. How am I, a timid teenager, supposed to give orders to a genuine Red Army officer—in his mother tongue as well? I could tell him my name and age, what my Dad does for a living (he’s an engineer) and what my mom’s job is (bookkeeping). But the officer could care less about that. He’s only concerned with his troops finding a comfy place to camp and use their radar. They are Russians; they take what they like. I wish the forest soil would open and swallow me up. I can sense my dad’s disappointment. Years of lessons, all a waste of time. A single word occurs to me. “Ubiraz“, I stutter at the officer. That means to tidy up. I don’t know if he understands me. Maybe my pronunciation is wrong. Dad and I leave the garden, driving off in our Trabant.

(To be continued in Part IV, next Saturday…)

![Wine & Paint event on 9 Nov. 2024 at Felix Restaurant, Leipzig. Photo: Florian Reime (@reime.visuals] / Wine & Paint Leipzig](https://leipglo.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/pixelcut-export-e1733056018933-480x384.jpeg)