You’ve probably heard of Bauhaus, especially given its centenary this year. But what makes it so famous?

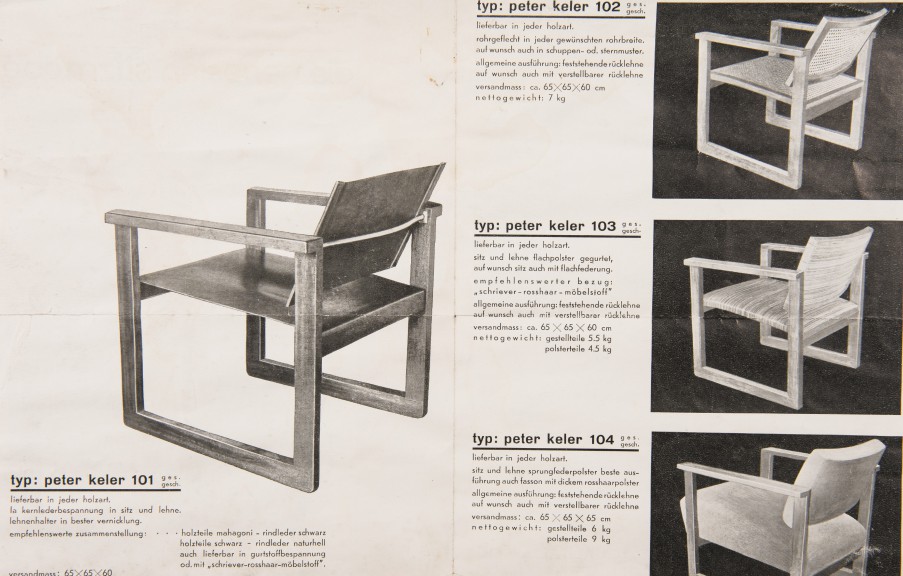

Bauhaus started in 1919 in Weimar, when Walter Gropius had the idea of twisting art and stripping it of all flowery details, calling it a new type of art. Considered one of the most definitive designs of the modern age, the Bauhaus style is marked by its minimalism and absence of any ornamentation. It is known for its geometric purity and concept of harmony between function and form.

The GRASSI Museum here in Leipzig commemorated the 100th anniversary of this legendary movement, in 2019, with an exhibition welcoming not only Bauhaus enthusiasts, but also the Bauhaus curious. The exhibit entailed little samples of every aspect surrounding the movement: from chairs to didactic books, theater to tapestry.

Bauhaus can be translated as “school of building” or “house of building.” Its best-known school was built in Dessau, and changed forever the idea of what architecture and design looked like.

The school for arts and design believed in variety, in the combination of the fine and the applied arts. Unlike other art schools of the time, Bauhaus taught numerous areas of the arts, such as sculpture and pottery, a perfect mix of arts and crafts, and an embrace of new technology.

It reinvented the fields of architecture, design and graphic design and how they can shape society.

How did Bauhaus become Bauhaus?

Modernism, a movement associated with the dawn of the 20th century, was one of the major factors for the rise of Bauhaus. Interrupted by World War I, it reemerged after 1918, with full force and even more radical ideas. Minimalism and experimentation were the norm in modernist architecture and design, as well as in modernist literature and theater, among other fields.

There were practical reasons for that. Germany’s industrialization and post-war economic situation greatly influenced the movement. “The Great War” had shaken everything up, and Germany was broke. No one had money to build great houses and buildings with intricate details, or have furniture that was exclusive and designed for one specific room. People had to make do with what they had. And make do they did.

Industrialization and the rising culture of mass production opened up doors. The Bauhaus School took advantage of that, implementing mass production in the curriculum.

The students were learning about building and designing furniture and, on top of that, making them in workshops at the school. One of the philosophies of the school was to create harmony of craftsmanship in mass production.

Besides that, the shift in Europe’s political atmosphere after the war became evident with the rise of the Soviet Union as the first socialist state. Even though he never admitted or spoke about it, Gropius had a very socialist way of going about architecture, making his creations thinking about the community rather than the individual.

The style can be characterized as simple, intimate and efficient.

Today, when we think of Bauhaus, we think of geometric shapes, the cantilevered chair (yes, that’s the name of the chair) and function. And we are not wrong. But Bauhaus is so much more than that.

They were fundamentally rethinking the world.

Bauhaus was a lifestyle, an alternative way of life in the 1920s. In the GRASSI Museum we can see, for example, advertisement posters that, due to the lack of strong colors and intricate details, are even more eye-catching than the ones we are used to.

The movement influenced theater, with Oskar Schlemmer being one of the most prominent Bauhausler to work in the field designing costumes. There is one Bauhausler, in particular, who became famous for her lifestyle – a quintessentially Bauhaus lifestyle, that is: Marianne Brandt, known for her designs of the industrial lamp as well as her teapot. All characteristically minimalist, of course.

Brandt was the first ever cool Instagram girl. Even before Instagram. She took pictures of food and landscapes, which can be seen in the exhibit in the GRASSI Musuem. She also took pictures of herself. Yes, you read it right. She took selfies. Artistic ones, obviously. She was cool, remember?

Leipzig was and still is a hub for the centenarian movement.

There are some Bauhauslers who are Lepzigers. Take Arno Rink (1940-2017), for instance, a painter who lived and worked here in Leipzig, implementing some of the Bauhaus philosophies in teaching his students.

Proponents had actually considered bringing the Bauhaus art school to Leipzig before deciding to settle in Dessau. The school ended up moving to Berlin in 1932, but closed the following year, when the Nazis came to power.

According to the Nazis, it was too communist to have a place in Germany. The movement seemed to fall into oblivion under the regime. After 1945, however, Bauhaus resurfaced and regained its prestige. To this day, it is recognized as one of the most celebrated schools of art and design in Germany and the world.

The Bauhaus movement has become part of the fabric of our society, with its indelible influence on the arts, architecture and daily life.

Where can we see it in architecture?

We see Bauhaus in road signs, graphic designs, advertisements, and great glass windows. However, Bauhaus reaches further than that. Or should I say nearer?

Walk 15 minutes in any direction here in Leipzig, and you will see a box-like building, with basic colors, sharp angles, an industrial air. That’s Bauhaus, still influencing our skyline and daily life.

The style is found all over Eastern Germany in GDR-era buildings – like the Plattenbauen. They were built for housing. Nothing more. Some would say that it’s not beautiful architecture, but imposing, nonetheless. Its angular corners and lack of ornaments had one function: a space for people to live in.

There’s a good chance that your home, even if not Plattenbau, is very Bauhaus.

You probably have at least one piece of Ikea furniture in your home. Am I wrong? Ikea is the epitome of modern furniture. But it is also the clearest reflection of Bauhaus influence. Wanna bet? Angular, geometric shapes, furniture of only one or two colors, function and form, not a lot of ornaments. Sounds a lot like Bauhaus to me, if I do say so myself.

Let’s do another test. Open your kitchen cabinets. Now count how many plain white plates and mugs you have there. That’s Bauhaus for you: simplicity, minimalism, function.

Now, can you tell me? Just how Bauhaus is your house?

The original version of this story was published here on 23 July 2019.