New LeipGlo column: Afro-German Connections

The Genesis

In Swahili there is a saying, Tembea kwingi uone mengi. It loosely translates to “travel far and wide so you can see a lot more.” It is also a concept that held no particular significance in my life before I was 20. This is because I grew up in a small village somewhere at the foot of Mt. Kilimanjaro. “The foot” here is technically untrue, but being able to clearly see the mountain every morning from my room validates my view. The mountain also links me to German Tanganyika, but I am stretching the connections here.

As with many villagers, a lack of exposure meant that my life goals had geographical limits. Life was simple. I admired the wholesale shopkeeper because in the village, the wholesaler was the gatekeeper of all things tasty and beautiful. The shop was a mark of having “made it”, and I wanted to make it. But I did not want a shop. I would be a teacher, because my mum was one. Her students loved her, and she could get anything she wanted from the shopkeeper. The dream was clear.

Stepping Out

Fast forward to the influence of TV and boarding schools. I got to know and meet girls with bigger dreams, curious girls with inquisitive minds who inspired me to dream big. By the time I started my undergraduate degree, the teacher had been replaced by a human resources manager. I did not know much about the job requirements. I simply liked the sound of the title and the promise of a polished office where I was the boss.

Two years in, the now advanced village mentality was introduced to policy making and development studies. I probably should have sampled philosophy as well, but learning Japanese was more appealing.

By the time my four years were coming to an end, the human resource manager was no more. A future change maker was now in charge. I would fight poverty, bring justice to the oppressed and make the world a better place. Armed with a scholarship to Manchester, the villager went global. I like to see this journey as a form of reverse voluntourism. Instead of waiting for the white saviour, I opted to ease the burden by learning how to be my own saviour. Simple reciprocity, really.

The “New World”

Manchester was nice to me. I fit in well, made friends and enjoyed great food. If you have been to England, you know that I am most definitely not referring to English cuisine. Well, there is the probable exception of an occasional shepherd’s pie. It was in Manchester that I understood what racism is and how it works. As a Kenyan (from the village), I had no previous interaction with the concept.

Manchester introduced me to intercultural communication and the black nod. The black nod is a look or actual nod shared between two black people, as a sign of acknowledging each other’s presence in a predominantly white setting. It is quite a lovely thing, even comforting, depending on how your day is going. It is, however, something I find conspicuously absent in Leipzig, but I am getting ahead of myself.

Manchester also taught me that racism is layered: it is a system where the darkness of your skin dictates the level that you occupy. Therefore, as a black African in England, I fall below the Indo-Pakistanis the same way I fall below the Turkish in Germany. Of course, the dynamics shift with the changing political environment, and men tend to have it tougher than women.

I have no incidences to report from Manchester though. Maybe I was naïve, but I have no stories to share, not even stares which I have now become accustomed to in Germany. Well, there was this one time that two lads were exchanging insults, and one’s constant comeback was “pak”’ which understandably irked the other with the immigration background under reference. Hearing the two lads argue, I crossed my fingers and hoped they would not notice the presence of the other who falls well below the “chain of racist command.”

Destination Germany

A few years after Manchester, I found myself in Germany, thanks to Google and the politics of securing PhD scholarships. With a taste of how racism works, I came prepared. Or so I thought. I quickly realised that England had not prepared me well enough.

The only thing in common with the English system here, is that as a black person, I am still at the bottom of the chain. I have friends (and I use this term VERY loosely), who profess their hatred for Muslims – especially the veiled ones. They deeply dislike the Turkish who refuse to integrate, and all the economic migrants from Sub Saharan Africa taking advantage of the “refugee crisis.”

But these “friends” love Döners and do not get haircuts from a German Friseur as they have a “safe sense of style.” Most peculiar is that they love Asian cuisine and almost exclusively date Asian women.

If you are like me, I find this brand of racism, or whatever this is, very confusing. I have therefore chosen not to try to unpack it. What I do is stare back at those who stare at me or just ignore them because staring happens a lot. I need to save my eye-power for my dissertation writing and random explorations.

This brings me to my goal here: sharing my encounters on things African in Leipzig.

“Historicity”

As a commonwealth country, Kenya shares a colonial history with 52 other countries, and is one of the 19 in Africa. Germany, on the other hand, has a much less visible colonial “relevance” across Africa, with the notable exception of Namibia, of course. When I came to Germany therefore, I had very low expectations on Afro-German connections. My first unlearning was with the Cameroon connection, though that tends to be more visible in Berlin. Other than that, most of Africa is to be found in museums and through music among those with an “exotic” palate.

There are those with a political awareness, thanks largely to the independence and postcolonial movements of the 60s and 70s. As with all things political, however, I harbour a strong distrust. If you think I am overly sceptical, refer to the current Marshall Plan for Africa. The rationale alone can be the subject of a PhD thesis. Out of pure bias, and in the interest of sanity, of course, I much prefer to focus on the (sometimes) hidden African connections.

Afro-German Connections

I recently bumped into an unlikely place where I found a clue to understanding a foreigner’s life in Saxony. The Zeitgeschichtliches Forum Leipzig’s current exhibition is titled “Our History: Dictatorship and Democracy after 1945” (Unsere Geschichte. Diktatur und Demokratie nach 1945).

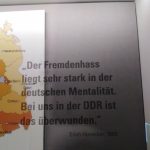

Somewhere in the middle of the exhibition is a section on Fragen an die DDR (questions to the GDR) with a special drawer for Fremdenfeindlichkeit (xenophobia). In it is a diary entry from Beate Salimo on the racist attacks to her and her Mozambican husband. This entry, made in 24.07.89, negates Erich Honecker’s statement that even though hate against immigrants is historically very strong in the German mentality, the GDR had managed to overcome it. Well, the comforting news is that this was in Dresden, “the valley of the clueless” – so referred as the region could not receive Western media broadcast.

Consciousness

As a Leipziger, the wonderful news is that the revolution for reunification is rooted here. This means that the Saxonians here are mostly the positively conscious kind of humans. You could call them “woke” if that fits your interpretation of the term. You can find more details on this at that exhibition, as well as the Nikolaikirche’s own exhibition.

It is with this awareness that I walk with ease on the streets of Leipzig, ready to explore what African connections are to be found… and how they are presented.

I am coming around to the realisation that my passion is now on connecting the dots between different levels of society and sharing this with as many people as possible. Does this mean that the teacher is now back to stay?