My visit to Germany in March 2014 began in a most memorable and, for me at least, distinctly German way.

Immediately after landing in Frankfurt, I boarded an InterCity Express for Berlin. Just before our first station stop in Frankfurt proper, the train came to an unscheduled halt right next to an allotment garden colony. Germany received an early spring and it was a glorious day: 25 C, sunny with the trees and gardens lush and green.

As I sat at my window seat reading the paper, a movement in the corner of my eye caught my attention.

I turned to see the high shrubs directly adjacent to the tracks rustling.

A second later, two hands emerged to pull the branches aside; and when they did, a 70-something gentleman (on this point I am perfectly clear), emerged, his shock of white hair only slightly contrasted by the even whiter tone of his pasty skin. All of his pasty skin in fact.

And for the next 10-15 seconds those travellers with the fortune to have been gazing upon the garden colony were subject to a scene of full frontal nudity courtesy of this elderly man. His curiosity satisfied, he let go of the branches, turned and disappeared Yeti-like back into his plot, and my mind began formulating “Welcome to Germany” tourism posters featuring the image that had just burned itself into my brain.

Before I went to live in Leipzig in 1999, I didn’t consider myself particularly prudish or uncomfortable with public nudity. If I had reflected upon this, however, I likely would’ve recalled a story from my youth that revealed some Ur-anxieties with the concept.

I was probably eight and my younger brother about six when my parents announced that our family would be going to a retreat weekend at a monastery just outside our hometown of Saskatoon. My brother and I balked at the idea, a reaction that confused our parents. Why, they asked, did we not want to go? We answered it was because “a monastery is a place where people get undressed in front of each other.”

I have no recollection where we got that idea from, but I do remember our distinct unease with the plan despite our parents’ assurances that nothing of the sort would happen there. (It didn’t; in fact, to my great relief, we had a private room to ourselves!)

Years later, as a young adult, I thought such hang ups about public nudity were behind me, but that was likely because living in English speaking Canada, I was never confronted with any.

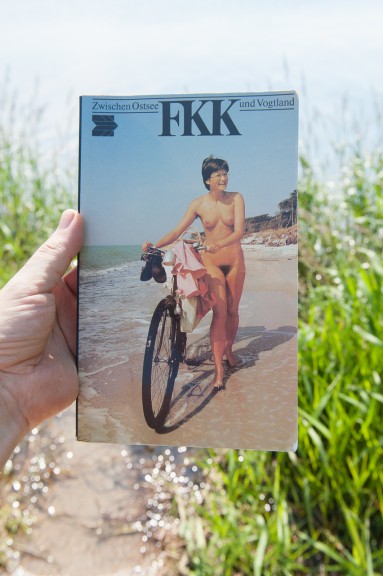

Before relocating to Leipzig, I was aware that Freikörperkultur (FKK), “free body culture” or what in English would be known as naturism or nudism, enjoyed considerable popularity in Germany, particularly the former East.

It did not occur to me that I would encounter this cultural practice during my time there or that it would cause me any problems. But encounter it I did.

During my stay in Leipzig, I had some nagging health problems. My roommate, a native Easterner, was convinced that a visit to a sauna would help kick start my immune system. He invited me to join him at the health club where he was a member and, thinking it couldn’t hurt, I accepted.

As I was getting my things together, he saw me grab my swimsuit and told me that I could leave it behind, that it wouldn’t be necessary. I assured him that it most certainly was, but he replied: “You’ll only draw attention to yourself if you wear that.” If only I had listened.

The health club was housed in a converted warehouse in a former industrial park. The spartan interior with its cement floor betrayed the building’s former use, but it was entirely functional.

We headed to the change room where my roommate stripped down to nothing and I pulled on my swim trunks before we made our way into the sauna. Now, my only previous sauna experiences had come at my Toronto gym, which was in a Jewish community centre. There the saunas were gender specific and in the men’s at least, it was standard practice to drape a towel around one’s waist.

Things were different here in Leipzig.

My memory of the moment we entered the sauna is of stepping into a dimly lit space and, through a cloud of steam rising from an oven in the centre of the room, slowly making out a sea of naked bodies of all shapes, sizes and, to my surprise, genders. I was, of course, the only one in a swim suit and, as I’d been warned, immediately felt completely, utterly conspicuous.

It wasn’t complete mortification, but it was remarkably close.

Afterwards my roommate suggested we reacclimatize ourselves in the “relaxation area”. This was essentially a long hallway under the building’s corrugated steel roof, decorated with “sun spot” travel posters and dotted with reclining chairs that sat beneath buzzing heat lamps.

Here too it was “all nude, all the time,” and we had to pick our way to chairs through a gaggle of naked, 60ish women who reclined leafing through back issues of SuperIllu, a sort of eastern German version of People magazine specializing in former GDR celebrities and their offspring.

While the experience was memorable, it didn’t seem to help my immune system. I don’t recall it being particularly relaxing either.

And yet, naturism enjoys a relatively long history in Germany, having emerged as a cultural movement of some import in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In its early years, naturism slowly became associated with vegetarianism, pacifism and the progressive politics of radical socialists who saw in the practice a way to break down class barriers (Michael Hau, The Cult of Health and Beauty in Germany: a Social History, 1890-1930: University of Chicago Press, 2003). During the Third Reich period, nudism continued to be tolerated but was consigned to sites where the general public would not run the risk of encountering practitioners.

In the early years after the founding of the GDR, FKK emerged as a political fault line within the East German elite.

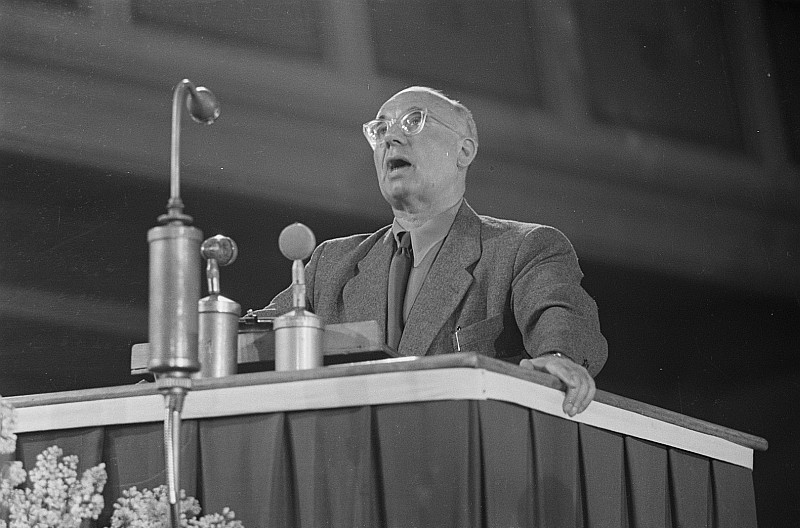

One anecdote has it that then GDR Minister of Culture (poet and FKK opponent) Johannes Becher took it upon himself to patrol a Baltic beach one evening to ensure that all was in order. When he encountered a woman sleeping in the nude, he is reported to have yelled: “Are you not ashamed of yourself, you old sow!”

Several years later, when Becher delivered the laudation for renowned East German writer Anna Seghers on the occasion of her receiving the GDR’s National Prize, he began his address with “Dear Anna”, only to have Seghers interrupt him with the comment, “To you, Hans, I will always be ‘the old sow’” (“FKK in der DDR”, einestages, Spiegel Online).

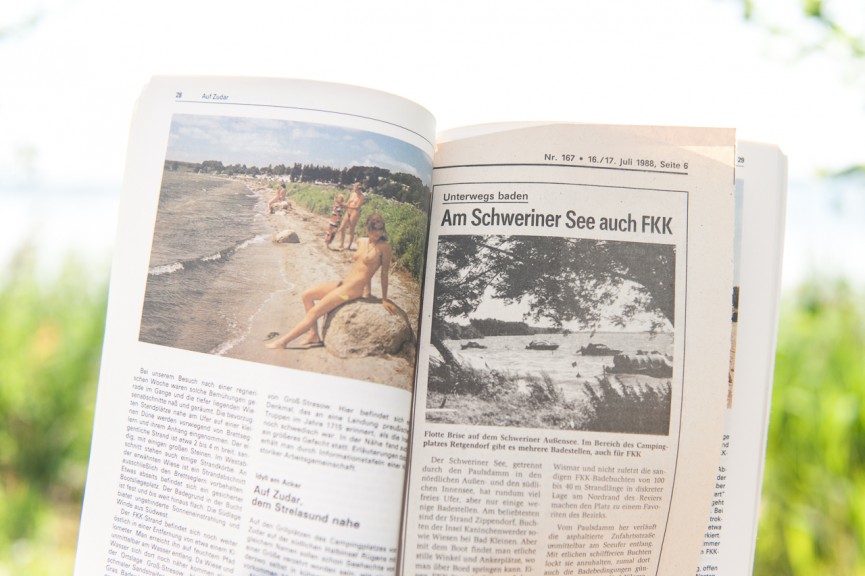

When authorities moved to prohibit nude bathing at all Baltic beaches in the mid-fifties, the resistance was remarkable, with many citizens registering their protest through letters and petitions. These often made political arguments invoking FKK as an example of the victory of progressive ideals over “bourgeois, capitalist and religious values” (“FKK in der DDR”).

Remarkably, the government backed off and over the years, FKK established itself as a popular pastime within the GDR.

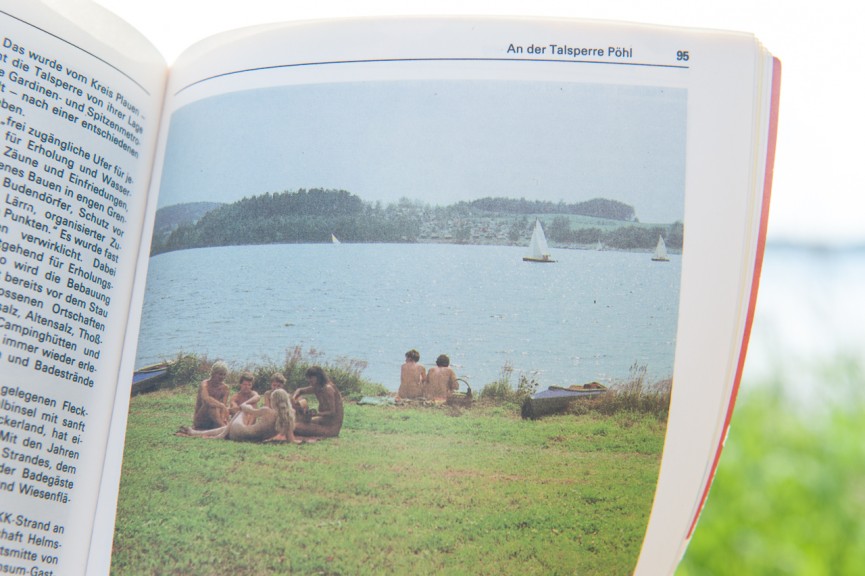

There were public beaches reserved for nude bathers, but another popular way to practice this pastime was through membership in a local FKK club, which would’ve had its own grounds to use for such purposes.

These clubs were incorporated as sections of local sport clubs, and many thousands of East Germans were members of organizations. In 2013, a photo purporting to show German Chancellor Angela Merkel in her birthday suit as a young woman made the rounds online, causing some stir internationally but little within Germany itself; there the news was generally met with a shrug.

Merkel herself remained mum. If it were true, it would be little surprise, given Merkel’s age and the popularity of FKK in the GDR during her youth.

Not surprisingly perhaps, East German nudism has been the subject of a number of studies, academic and otherwise, and these in part examine the reasons for the movement’s particular popularity in considerable detail.

For me, however, I find it hard not to get beyond seeing FKK as a manifestation of GDR citizens’ desire for personal freedom, something relatively hard to come by in East German society.

My Leipzig roommate and his family were avid FKKers. In fact, during the year I spent in Leipzig, his father assumed the chair of the nudist club to which the family had belonged since the GDR times.

During a weekend visit to A., my roommate’s hometown, we took a walk that included a stop by the club’s grounds. Thankfully this happened in the fall, so we were all bundled up, but the site was a modest set-up with a small pond, a grassy area for volleyball, badminton and sunbathing, and an adjacent wood for those wanting to do a bit of wandering about. Very simple and reminiscent of 60s era campgrounds once common to North America.

I asked my friend’s father, Mr. R., how he had come to FKK. His experience strikes me as representative, given the social milieu it arose from in his case:

“My mother, when she was a youth and young woman, was a member of the so-called ‘Youth Movement’ that was popular in the early 20th c. These groups despised the social coercion and bombast of the Imperial Era (late 1800s/early 1900s, ed.) and thought they were passé. As a sign of this, young men and women would go on hikes together, joined in choirs and singing groups, they even went camping together without being married, oh, the scandal!, and FKK was part of this too. These were all ways for young people to demonstrate how they were different from the older generation. Now once my mother married, oh my goodness, her FKK days were behind her, but through her we heard about it.” (All quotes from a letter from Mr. R. to author, 8 January, 2014.)

When Mr. R. and his wife started their young family, the attraction of FKK was, he related, practically motivated: “In the beginning, we found it liberating, but also practical to go without damp swimsuits, and not to have to struggle to get the three boys into theirs. Once they hit puberty, the boys went their own way and each started wearing bathing suits, for a while anyway. But with time, they all went back to ‘without’.”

In regards to their motivations for pursuing FKK in their free time, Mr. R. explained, “When we first started going to the FKK pond regularly (in the 80s), there were no unsavoury ulterior motive (unsauberen Hintergedanken in the original), we just liked the atmosphere.”

In my diary account of that visit, I recorded that the club was named Roter Heil, a rather peculiar name in my estimation.

First, the use of the word “Heil” struck me as remarkable, given its close connotations to the Nazi era. How, I wondered, could this have passed muster in the GDR, where even a hint of National Socialist thinking was sure to set off alarm bells?

The use of the adjective “red” made more sense in this regard, and I roughly translated the name as “red well-being.” Surely there was more to this name. Mr. R. set me straight: “The name is actually Roter Hiehl, and is a reference to the river that runs through the parcel of land the club uses. It has nothing to do with the Arbeiter Turn und Sportverein (Workers Gymnastics and Sport Club) that was founded by the Communist Party [during Weimar Era], oh no!”

Initally the FKKers of the town of A. gathered at the local pond on an ad hoc basis, but were soon informed that they needed to formalize the arrangement by getting official approval (not something peculiar to the GDR, Mr. R. points out. In his view, the situation is no different today.). To get this approval, Mr. R. told me, tongue firmly planted in cheek, “the brave defenders of nudism took part in a number of ‘conversations’ with the comrades in the state apparatus with the result that our group became the FKK Section of the sport club ‘Motor N.’ (the ‘Motor’ designation an indication of the club’s factory sponsor, a metal works, ed.).”

This arrangement persisted throughout the GDR era, but the club was granted its independence after Wende when “Motor N.” dissolved itself.

As anyone who has spent time in Germany will tell you, club culture plays an important role in its society.

Laws and bylaws are set up to support the club structure, and many Germans are members of several such organizations through which they conduct their free time activities.

In the post-Wende world of eastern Germany, clubs have become one way of measuring the social health of communities, and the situation facing Mr. R’s FKK club provides a good example:

“Our membership is about half of what it was ‘then’ [in GDR times, ed.], we simply don’t have the young people. But this is not peculiar to us, it’s the same for many clubs. In our case there are several reasons for this. First, there are simply fewer of them around [many of them leave smaller towns and cities to seek opportunities in major centres, ed.]. Second, there’s a general tendency away from commitments which might tie one down. Third, our facilities are rather ‘spartan’… These days we might more accurately call ourselves a ‘Seniors’ Club,’ but we’ll keep going as long as we are able to keep the grounds in order.”

In the mid-90s, an incident involving the club also served to illustrate differing attitudes towards sexuality that continue to exist in the East and West.

During these years, stories on these differing attitudes were a constant in German media, something my eastern friends found confusing and bizarre. For them, FKK had nothing, or little, to do with sex or sexuality, but western media seemed incapable or unwilling to try and understand this activity in any way other than as a borderline perversion or fetish.

So when a sex-themed TV “news magazine” approached the club asking whether it would be interested in being featured, my roommate advised his father to turn them down. He argued that producers would cast the club in a poor light or worse, but Mr. R. and the other club members went ahead with it and let the show shoot on their grounds.

The piece featuring an interview with Mr. R. and several staged scenes using a couple that producers had brought with them was “not really what we had in mind”, Mr. R. wrote, but if he had a problem with the way the club was presented, he didn’t communicate that to me – a welcome example of restraint in the “culture wars” that sometimes trouble relations between eastern and western Germans.

By John Paul Kleiner

(Originally published on 8 August 2014 on Kleiner’s blog, The GDR Objectified)

John Paul Kleiner lives in Toronto, Canada, and holds an M.A. in History from the city’s York University. He lived in Leipzig at the dawn of the new millennium, and did much traveling around the former GDR. Kleiner wrote his major graduate research paper on how “Leipzig dealt with manifestations of the East German state in its public spaces during the ten years following German unification.” The GDR Objectified blog features his “collection of East German ephemera,” and shares “information on these items with the aim of providing a window onto East German history in an historical and/or personal way.”

![Wine & Paint event on 9 Nov. 2024 at Felix Restaurant, Leipzig. Photo: Florian Reime (@reime.visuals] / Wine & Paint Leipzig](https://leipglo.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/pixelcut-export-e1733056018933-480x384.jpeg)