I jump off my bike, hands frozen, and run up the escalator to CineStar at Leipzig city center. Justina, the photographer, is already waiting, pacing back and forth. “From which side will Werner Herzog appear? Why aren’t there more cameras around?”

“Remember how the DOK Leipzig people said that not that many photographers from media outlets work the festival? That it’s usually their own photographers?”

“Ah, yeah.”

“Oh, look. That’s him, that’s him, that’s him…”

And just like that, inconspicuously, the director of Fitzcarraldo walks in.

The man who stubbornly believed that a steamship could be moved over a mountain, just like the film’s protagonist, even after laborers had died during the shoot and his crew had abandoned him. Who’d returned to the Peruvian jungle years later to give a “guerrilla style” workshop to filmmakers who’d be willing to whip up a complete production in nine days. Who’s habitually blurred the line between “truth” (a word he says should be “touched with a pair of pliers”) and poetry in his films – even in his documentaries, which are sometimes partly or fully scripted.

A man who, depending on the question he’s reacting to, can go from self-deprecation (urging people not to watch his old interviews) and graciously acknowledging other filmmakers (like his collaborator André Singer, for setting up Meeting Gorbachev), to loudly tooting his own horn.

“Although I don’t use the Internet very much, I made the only competent film on the Internet,” Herzog would tell a packed Kupfersaal in Leipzig during his “Ecstatic Truths” talk, on 30 October.

Maybe I wouldn’t hesitate to make such statements, either, if I’d written, directed, shot and/or narrated 70 films, many of them important, for nearly 60 years. On what seems like every continent. With no signs of stopping, at age 76. Or if I’d managed to charm – within minutes, when there was barely any time left – everyone from death row inmates to Mikhail Gorbachev into baring their soul to me on camera. (He insists “there’s no technique.”)

Herzog encourages aspiring filmmakers with a vision and smart phone camera to just do it (mentioning, for instance, the “well-made” film Tangerine). He prides himself in never going overbudget in his own films, sometimes even keeping them underbudget: “The producer who did Bad Lieutenant wants to marry me now.” He’s irreverent and advises one to avoid film schools as much as possible, some of which “almost methodically incapacitate” their pupils from, well, making films.

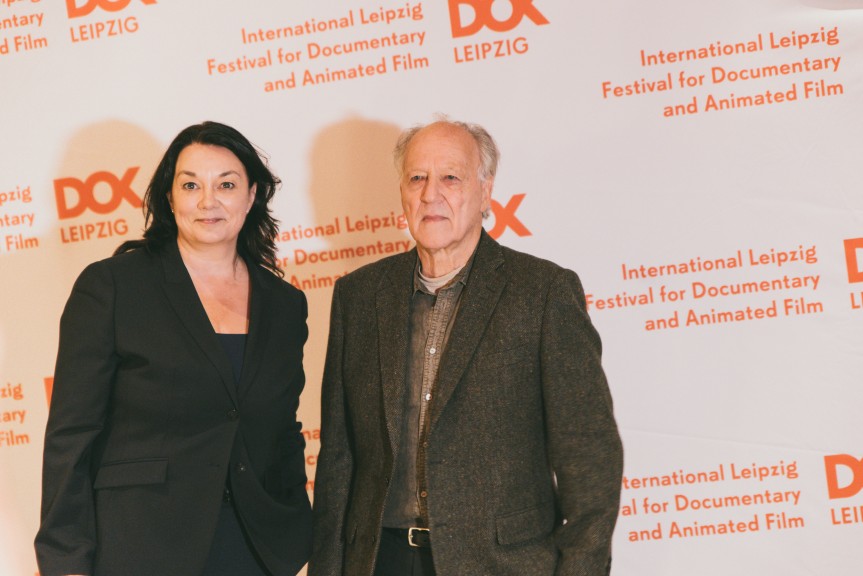

And now, here we are. And the iconic German director is moving a small circular table himself at CineStar so that TV can interview him with more silence, and probably better light. Justina circles him with her click click clicks, while I follow him with my eyes, from a distance. He poses for a shot beside the festival director, smiles for selfies with fan girls.

Suddenly, someone from DOK Leipzig comes over to us and whispers, “We’re sneaking Werner Herzog out to Hauptbanhof. He’s spontaneously decided to watch the opening film there.”

I have a ticket to the main premiere at CineStar theater 8, but immediately choose to go and wait for Herzog in the train station’s Osthalle instead, where the free DOK Leipzig screenings take place for anyone to see. Justina and I can’t wait to see his reaction, in that much less measured environment, in the midst of das ordinary Volk. We get butterflies imagining.

Instead of waiting in line for an overpriced glass of wine at CineStar, Justina and I decide to buy provisions for the cold way to the train station at the Petersbogen Lidl, downstairs from the cinema. Wine. Cheese. A version of chocolate.

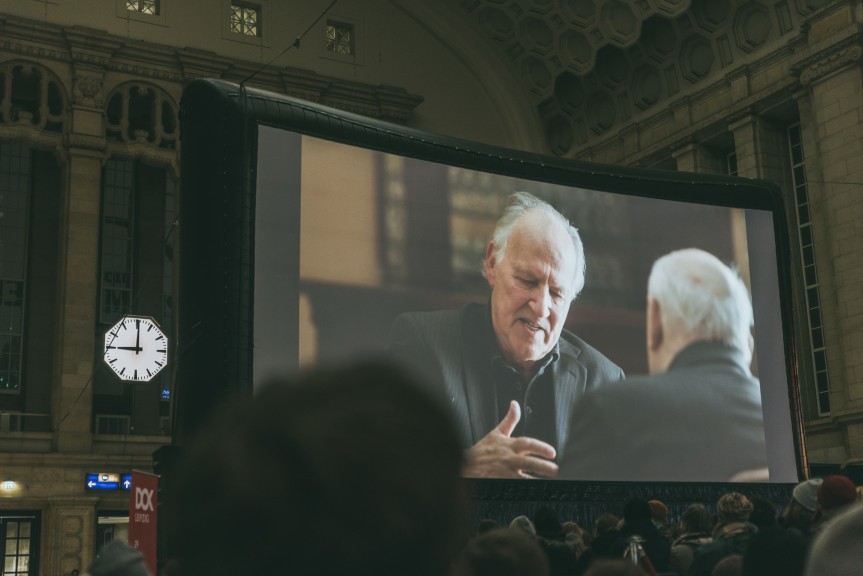

We are sitting on the floor of Osthalle, along with many others. All the seats are taken. The opening film is Herzog’s newest, Meeting Gorbachev. In it, he plays the role of interviewer too. It’s the film’s European premiere.

The director’s German voice echoes above his English voice (he’s dubbed himself), reverberates around the train station. Gorbachev’s voice, in Russian and German. Their heads look massive on the gigantic screen, which only magnifies the weight of the history they are discussing.

Although Gorbachev is opening up, although we see his sentimental side, and he and Herzog look like two old friends catching up, and we’d just seen Herzog right in front of us, Justina and I feel a world away from these two titans. Part of it is the echo and the lack of subtitles. But this is quite different from most DOK Leipzig documentaries I’ve seen, which focus on showing ordinary people from a unique angle, giving the feeling that the spectator is tagging along with them.

Justina, who is from Lithuania, spots a piece of historic footage she can directly relate to and is compelled to bring up. She points to the screen and whispers:

“It’s the Baltic Way. My parents were there, holding hands. The world’s longest human chain.”

It’s then that I realize the beauty of the moment. Gorbachev’s voice echoing in the main train station of the city that set off the Peaceful Revolution. The co-director of the film coming to watch it there. We’re watching the clock above the entrance. Any time now…

We reach the end of the block of cheese, and bottom of the bottle, before Herzog materializes, standing in the crowd towards the top of the stairs in Osthalle. The film will be over soon too.

“That’s him, that’s him, that’s him…”

Click click click.

It’s amazing to watch Herzog, even from the floor at the bottom of the steps.

He looks transfixed. (Later, he’d describe it as “the most wonderful kind of screening you can have as a filmmaker.”) Meanwhile, his own massive head and voice continue to fill the screen, the hall. No one but the few from the press seem to have noticed he’s there. And they keep a respectful distance. Backpackers run past him, without a second look. He continues to stand, without even a sway, through the end of the film. Then he agilely descends the stairs and walks to the screen, where he is to give a brief talk.

The announcement that yes, that is Herzog coming over, gets a lot of applause from the audience.

Herzog says – and repeats the next day at “Ecstatic Truths” – that Gorbachev has been gravely ill and had to be taken by ambulance from the hospital to their chats for the film. That’s why Gorbachev, now 87, states in the film that he’d like another two years to live. According to Herzog, an IV has been hidden under Gorbachev’s clothes. Some years ago, Gorbachev lost his beloved wife to leukemia, along with his joie de vivre. We see that in the film (real tears).

“This is a type of testament, involving two great men; it doesn’t matter if it’s a masterpiece, or if it’s innovative,” a film critic tells me later, at the DOK Leipzig Opening Party (at MdbK), where Herzog also stands around socializing – apparently with whoever approaches him – while many hurry to try to nab a place to sit.

But the German director doesn’t strike me as a people-pleaser.

Perhaps one cannot be, after all, to make movies that truly matter. Herzog, for instance, doesn’t hide his fondness for Gorbachev, and for Russia itself. He tells the audience at the Hauptbanhof that Russia should stop being demonized, since it’s a “natural partner.”

He gets less applause in this case, but the next day at the Kupfersaal, the public is more receptive to the idea.

Many in the “Ecstatic Truths” talk are fans. One can tell by their questions and referencing of Herzog’s work, and by their rippling applause and delighted laughter, even through the inflated statements.

Herzog in person can capture your attention from beginning to end, and he knows it. Even more so than his – as he describes – “stylized” narrator’s voice when clips from his richly colored, scored and scripted movies appear across the screen behind the stage.

The filmmaker, who is also famous for his excellent writing and, of course, narration skills framing many of his films, reveals to the audience that he’d rather read books than watch movies. He only watches three to four movies a year on average, “and most of them are lousy. (…) Depth for me comes from reading and from traveling on foot.” He affirms that reading is essential for making great films – and taking really long walks can be as well.

“I travel on foot when there’s a deep existential reason for [it],” he elaborates, reminisces. “I set out [traveling on foot around Germany] to hold the country together and make reunification possible.”

Then the self-deprecating side of Herzog comes out again, to end the talk on a comical note. The audience is laughing to tears as a clip from the thriller Jack Reacher, starring Tom Cruise, is shown. Herzog appears here as a cavernous-voiced villain alongside Rosamund Pike – his head much less massive, and voice less powerful, than back in the Osthalle. He chuckles right along with us.

Werner Herzog’s films at DOK Leipzig (HOMAGE)

Grizzly Man (2005)

Wed 31 Oct, 10 PM, Schaubühne Lindenfels

Screening number: #384 (tickets)

Little Dieter Needs to Fly (1997)

Sat 3 November, 12:45 PM, CineStar 5

Screening number: #622 (tickets)

Block of short films

Herakles (1962) / Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe (1980) / Wodaabe – Die Hirten der Sonne (1988)

Sat 3 November, 10:15 PM, Cinémathèque Leipzig

Screening number: #695 (tickets)

Meeting Gorbachev (2018)

Sun 4 Nov, 8 PM, CineStar 6

Screening number: #734 (tickets – APPARENTLY SOLD OUT)