LeipGlo column: Literary Parlor

Words and plots brood in the dark cocoons of a writer’s mind. The newly-hatched literary monarchs or common blues all briefly bask in the sunshine: in the best case, to be admired, worshipped and pinned for display long after their creator’s lifetime; in the worst, to spend their short life unnoticed. The entomology of writing is one of the least fathomable or predictable. Yet, are there any recipes on how to succeed? In our column Literary Parlor, we invite international award-winning authors for a virtual cup of tea, coffee or whisky, to unveil some of their art and craft secrets.

Literary Parlor Part II: Robert Krut

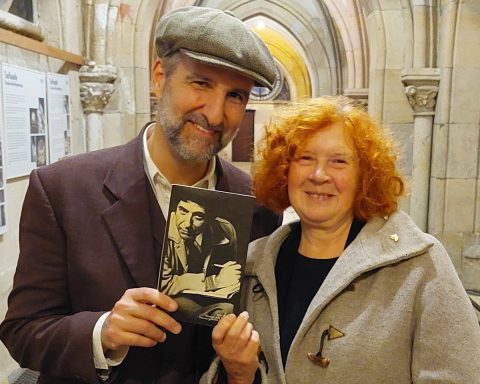

Robert Krut recently released his third book, The Now Dark Sky, Setting Us All on Fire (Codhill Press, 2019), which received the Codhill Poetry Award. Previous collections include This is the Ocean (Bona Fide Books, 2013), which won the Melissa Lanitis Gregory Poetry Prize, and The Spider Sermons (BlazeVox, 2009). His work has also appeared widely in journals like Gulf Coast, Passages North, Blackbird, The Cimarron Review, and more. A long-time educator, he teaches at the University of California, Santa Barbara, in the Writing Program and College of Creative Studies. He lives in Los Angeles. More information can be found at robert-krut.com.

Interview by Svetlana Lavochkina

Have you ever considered writing a book on “how to” for an audience wider than your poetry class students?

One of the aspects of teaching that I love is the chance to talk about writing (poetry, naturally, but really all forms) with people in real time, in the room, face to face. Each person is unique, so while there may be certain definitive ideas I want to share, those thoughts can change in tone, in meaning, and in delivery at times.

When sharing views on writing, I like to be able to frame it with someone else, as opposed to putting it out into the world without seeing my conversation partner’s eyes. With that in mind, I’ve never really been drawn to writing a “how to” book or something of that nature, simply because it doesn’t gel with my personal sensibilities as a teacher and writer.

That’s not to say I don’t love books like that, of course – there are so many I’ve turned to, and suggested to students over the years. It’s just for me, it’s never been something I’ve felt compelled to try. Importantly, too, I’ve seen my own approach change frequently over the years, as well as my own feelings about what does and does not make for a great poem, so I have to admit, I’m nervous to put down in writing my thoughts on “how to do it” or “how to do it well.” For now, at least, I’ll be sticking to talking about process with people in a classroom, I think.

Did/do you have muses other than your favorite poets to inspire your work?

Absolutely! First, I find that locations and geography are wonderful sources of inspiration – if I need a jolt to my writing (and sometimes when I don’t realize I do), simply strolling through particular areas can spark ideas. Here in Los Angeles, it is rare that I walk around downtown without finding some seed for a piece of writing. In similar location-based inspiration, our house is in a little neighborhood, filled with old bungalows near the studios. Taking a late night walk, with most of the houses dark, and just the street lights on, often offers up just the right atmosphere for new ideas.

And the other arts are, naturally, a huge inspiration. In the new book, there are pieces directly inspired by the visual arts (one particular well-timed trip to LA’s Museum of Contemporary Art made a big impact), film/TV (David Lynch’s recent Twin Peaks return felt like it was being transmitted directly into my mind), and music, so much music. Knowing there is another question about music to follow, I’ll save some of my rhapsodizing about that for later.

I’m lucky, too, to live in a town where so many of my friends are involved in the arts – being able to go see a friend’s film, or their band, or their art show, or their play, or, of course, poetry reading, always acts as a sort of creativity-defibrillator.

What are your preferred genres in music, if any? Do you ever write while listening to music?

This may be too broad of an answer, but I’m hard-pressed to think of a genre of music that I don’t like. Music led me to poetry, through people like Bob Dylan and Patti Smith, and I can’t overstate how much of an impact it has made on my love of writing. While I don’t listen to music while I’m actually writing, it plays a huge role leading up to it, during the revision process, and in the brainstorming periods. actually wrote a long piece about this very point for the great journal Superstition Review here.

It’s a coincidence to be answering this question this morning, in fact, as just last night I saw the incredible Kamasi Washington here in Los Angeles, an artist who directly influenced the writing of my new book. His music truly inspired, and sometimes guided, the poems, and the collection as a whole, at various points. Like his work, lots of genres of music, and various artists, inspired the new book (there is a playlist for the collection, in fact, on Apple Music and Spotify), and they were all a constant through the process.

Your poetry clearly has a noire magical realism touch. Is there a connection to your “real life self?”

In terms of my “real life self,” I suppose it’s just that I try to treat anything magical, or surreal, or possibly out of the framework of waking life, as entirely real, and concrete, and then let it appear in the poems. And the flip side of that coin is to consider anything that appears in my imagination as fully concrete and possible in daily life.

A few months ago, I was at a museum. A person was standing in front of me, in front a huge canvas. He turned around, and his shirt had a phrase on it that jumped out at me so much that I instantly memorized it while he stood there for a moment. I thought it must be the name of a song I’d never heard, so I slipped into the hallway to look it up on my phone. Nothing came up. I searched the exact wording, and a few variations, and after coming up blank, I typed the phrase into the “notes” on the phone and walked back into the gallery room. The person was still there, but this time I saw that his shirt simply had the name of a college on it.

But I had seen something else – to the point where I was inclined to step away and look it up (I have the Google search to prove it, no less). Since then, I’ve been using that phrase as a guide as I work on new poems, picturing it as the name of a collection I haven’t written yet. Did I see that shirt wrong? Did it not happen at all? Does it matter? In my mind, and for my writing, it was real.

What are the poems that took you the shortest/longest time to write?

All of them, ultimately, take a while, as even the ones that come out close to fully-formed require a lot of trimming and editing and adjusting, but there are definitely some pieces that turn into marathons. In terms of brisker pieces, there are two near the start of the book – “Divinity” and “You Can’t Escape When You’ve Been Underwater All Along” – that appeared relatively quickly, in a burst. The majority of each of those in their final versions is what was there to start, but small moments required some surgery.

With “Divinity,” a poet I admire read it and pointed out that an image near the end had already been used in a popular (and somewhat divisive) movie, which I had entirely forgotten about! Naturally, I changed it right away. With “You Can’t Escape,” it was more a matter of working on the line breaks and possible repetitive wording. Both of those, however, were pretty fast-moving.

On the flip side, there are definitely some pieces that took longer in the book – not surprisingly, they are the longer pieces. A poem being shorter or longer by no means represents how long you might spend on them, but with the longer ones in the book, I knew I wanted to slow down, and take a very deliberate pace. In addition, if you’re going to ask a reader to roll with you for a few pages, there should be a reason.

The two longest poems in this book, “The Cost” and “The Party,” exist in some other world, so it is easy for them to spin out into nothingness. It was important to me with these two to hold on tightly to the imagery and the pacing throughout. It took a lot of time, and a lot of editing, to get each of those where I wanted so that they could each move ahead in a sort of heartbeat rhythm, grounded by concrete details, to move a reader forward, and as each beat got further from reality, it still felt real.

To reflect back to your previous question, I wanted them to be “magical,” yet unfold that magic in careful, deliberate pace, to allow one foot in one reality and one in the other.