Trigger warning: this article quotes racist terms for descriptive purposes. The key term will subsequently be referred to as the ‘Festival of the M***’.

As protests against police violence and institutionalized racism have swept across the globe and revitalized long-standing calls to tear down racist statues and monuments, numerous oppressive practices of remembrance still succeed to evade the critical spotlight. The specific case I want to draw attention to leads us to the state of Thuringia, Germany, which last featured in international news in March, because of a political scandal surrounding Thomas Kemmerich, politician of the Free Democratic Party (FDP), who was voted into the position of prime minister with the help of Germany’s far right party, the Alternative for Germany (AfD). One year prior, in 2019, it was the small town of Eisenberg which became the focus of a contentious debate around race, memory, and political correctness.

The city decided to rename its annual festival that until then was simply called ‘Eisenberg City Festival’ into ‘Mohrenfest,’ which translates to ‘Festival of the Moor.’

In reaction to this, the Initiative of Black People in Germany (Initiative Schwarzer Menschen in Deutschland/ISD) published an open letter condemning the name as racist and demanding that the city change it. Numerous anti-discrimination and pro-democracy organizations followed suit and supported the letter. City officials, however, responded that the choice of name had been made in light of a longstanding local tradition which supposedly honors Black people. As they maintained, it could therefore not be seen as racist.

Said tradition refers to a popular myth, according to which a medieval duke of Eisenberg held a Black servant who, one day, was accused of stealing the golden necklace of the duchess.

Only moments before the Black man was to be beheaded for his alleged crime the duchess discovered the necklace in her Bible and stopped the execution. To restore the Black servant’s dignity, as goes the myth, he was freed from his servitude and a depiction of his head, blindfolded, was made part of the city’s seal. Based upon this narrative, numerous sites in Eisenberg contain the word ‘Mohr’ — to which I will refer in the following as the ‘M-word’ — within their names. The town’s most notable landmark is a fountain featuring the statue of a Black man dressed in a feather loin cloth, his upper body naked and his head bent back as he drinks from a cup of wine.

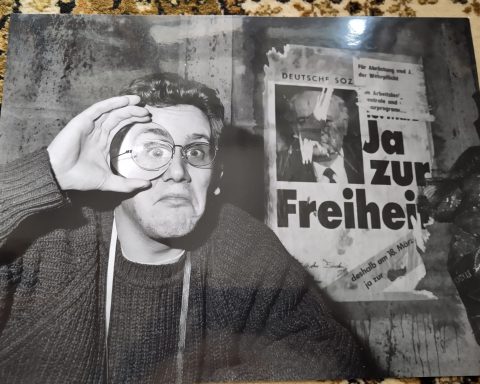

The open letter caught the attention of a few national newspapers and stimulated a heated debate on the use of the ‘M-word’ in Eisenberg. The above photograph from Twitter, depicting the reaction of a local butcher to the discussion, illustrates how both racist comments and expressions of deep resentment against progressives characterized many of the opinions and arguments brought forth in defense of the new name.

Eventually, a meeting between representatives of different anti-discrimination organizations, the mayor, and members of the city council took place. However, no agreement could be reached. According to a source who participated in the talks, most city officials did not show even a basic understanding of the activists’ criticism and made only vague promises of re-evaluating the case.

As was therefore to be expected, this year in early spring, the city announced that the ‘Festival of the M***’ would take place again.

The Corona pandemic thwarted these plans, but the city stated that it will reschedule the festival as soon as possible. A second open letter was published by a network of activist organizations in July which repeated the first letter’s authors’ original demands and extended an invitation to the city for another round of talks. But as the media showed even less interest in the matter this time, it largely slipped the attention of the public and, at first, city officials simply did not respond at all. In October, the city finally reacted to the letter; however, a meeting planned for mid-November had to be postponed because of the worsening of the pandemic.

Several lessons about race and racism in Germany may be drawn from this case.

Most importantly, the reaction of the city officials as well as of other defenders of the use of the ‘M-word’ reveals a persistent ignorance in German society about the history of colonialism, its continuation with ongoing forms of racial oppression, and even about the very nature of racism itself.

The central argument which underlies the city’s justification for their choice of name asserts that the ‘M-word’ may be separated from the history of colonial racism if its users had ‘good intentions.’

This reasoning represents an extreme example of a so-called intent-centered approach to racial discrimination which focuses exclusively upon the individual intention behind racist practices. Such a perspective does not only marginalize the experiences of the affected people, but by individualizing racism it also fails to redress any but the most egregious forms of racial oppression, and, thereby, ultimately contributes to the reproduction of the status quo.

The claim that in specific cases the use of the ‘M-word’ may be treated as separate from its history of colonial racism veils the oppressive structures that continue to define the term as well as the associations and stereotypes it evokes. “Decontextualization,” as the Critical Race Theorist Derrick Bell argued, “too often masks unregulated—or even unrecognized power.” While the ‘M-word’ in the German language was initially used for different population groups and with differing meanings, it has at least since the 18th century principally served for the explicit denigration of people of African descent.

And as an Afro-German, I have to this day never experienced anyone using the term in any but such a negative manner.

The popular myth, which city officials cite as evidence for their good will, is itself an inextricable part of these ongoing structures of symbolic oppression. As historical research suggests, it is very likely that the myth, in fact, does not date back to the Middle Ages, but to the 18th century when it was common that even at smaller courts, such as Eisenberg, nobles held enslaved Black people as servants.

The dominant representation of the myth in Eisenberg distorts these historical facts and, in their stead, creates a narrative of gracious White nobles righting a wrong. From this perspective, it becomes evident that the festival is not concerned with Black people and their lived experiences at all, but only with the celebration of an imagined White benevolence.

The omnipresent use of Blackfacing, the predominance of depictions of docile Black servants, and especially the play that re-enacted the myth, during which children were repeatedly encouraged to chant the ‘M-word’ at the festival in 2019, serve as further evidence that People of African descent only fulfilled the role of a racial fetish.

It is a projection surface for the imagination of an exoticized non-White Other in opposition to which the White Self forms and maintains itself.

The relatively unchallenged re-naming of the Eisenberg City Festival represents one among many painful examples of how Germany’s political culture’s move to the right has re-extended the boundaries of social acceptance of racist and xenophobic positions and utterances in the last few years. That the festival may well go into its second and perhaps even third year, is in this sense a gross failure.

It is a failure both of public media, which has not at any time seriously taken up the issue and tried to galvanize opinion against the festival, and of Germany’s political leaders on the state and federal level, none of who yet had the integrity to intervene and take a clear position against the ‘Festival of the M***’ in Eisenberg.

In 2016, Germany officially dedicated itself to the objectives of the International Decade for People of African Descent (2015-2024) to honor Black people and further racial justice. Any concrete actions still seem a long ways away, though. The case of the ‘M*****fest’ represents a particularly sad commentary on this, as it is ultimately not just about ‘political correctness,’ as some of the festival’s critics have argued, but epitomizes the persistent inability and unwillingness of German society to address its endemic structural racism.

Raja-Léon Hamann is a PhD student in Cultural and Social Anthropology and the current holder of the Anton-Wilhelm-Amo award for best graduate thesis at the Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg. His dissertation project, “More than just Black – Gullah Geechee Revitalizationism and Identity Politics under the Postliberal Condition in US American Society,” focuses on the interrelations between cultural recognition and economic redistribution as means to achieve social justice. His PhD project is funded by the Heinrich-Böll-Foundation.