I guess it can’t be too often that two people can laugh and make love, too, make love because they are laughing, laugh because they’re making love. The love and the laughter come from the same place: but not many people go there. (If Beale Street Could Talk, p. 15)

Love, its absence, and its absolute necessity for us, individually and collectively, is the fundamental theme of James Baldwin’s work. Not surprisingly, then, love is also central to my analysis of If Beale Street Could Talk.

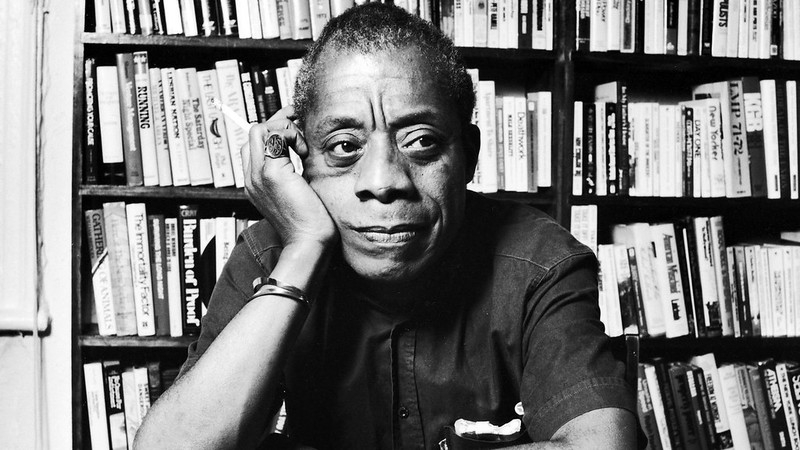

James Baldwin was one of the central voices of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.

Towards the end of that decade, however, his success slowly waned. A new wave of writers and literary styles arrived in the late 60s and 70s. New activists and social critics came with them, their work perceived as closer to the pulse of time. The Black Power Movement dominated the integrationist approaches of figures like Martin Luther King Jr. Black feminists were recognized as a force in their own right. Baldwin’s style of writing and his particular perspective on social issues might have seemed old-fashioned and out of touch. This includes his firm belief in love as a remedy for the ills of American society.

Beale Street was Baldwin’s fifth novel.

It was published in 1974, six years after Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone. Together with Just Above My Head, these three novels make up the later works of Baldwin. They are much lesser-known and, some critics argue, inferior to his earlier writings. I highly disagree.

At the time of publication, If Beale Street Could Talk received mixed reviews, some of which were devastatingly critical. Those that looked more favorably upon the novel emphasized the importance of the topics it dealt with. A 1974 New York Times review, for example, states that the novel’s focus on institutionalized racism should seem dated ten years after the Civil Rights Act. Unfortunately, it was quite the opposite. Another 40+ years and countless struggles later, we can still say

the same.

If Beale Street Could Talk received renewed–and much more favorable–attention only recently, with Barry Jenkins’ 2018 film adaption. Jenkins’ adaptation of the novel for the screen is certainly admirable. However, I highly recommend reading the book as well, even to those who have already seen the movie. The novel has more space to weave together the many different aspects of social critique contained within the story. Thus, in my opinion, it achieves much greater nuance and complexity than the film.

At first glance, If Beale Street Could Talk might appear relatively straightforward compared to Baldwin’s other work. It is quite short at only 173 pages (Penguin Classics 2019 Edition) and the sentence construction is simpler than in most of Baldwin’s other texts. Furthermore, it could seem that the novel is ‘just’ a love story. The book, indeed, is centrally about love. However, it does not exclusively focus on two people falling in love and the highs and lows of their relationship. Not to say that this could not also make for a great story.

The novel goes beyond a focus on the lovers and their inner lives.

It tells of the improbability and miracle of Black love in a racist society. Understanding love not only as a phenomenon involving individuals but as always taking place within a larger context. It is enabled and constrained by their respective social environments. Simultaneously, it is absolutely necessary for individuals and collectives to retain hope in the possibility of change.

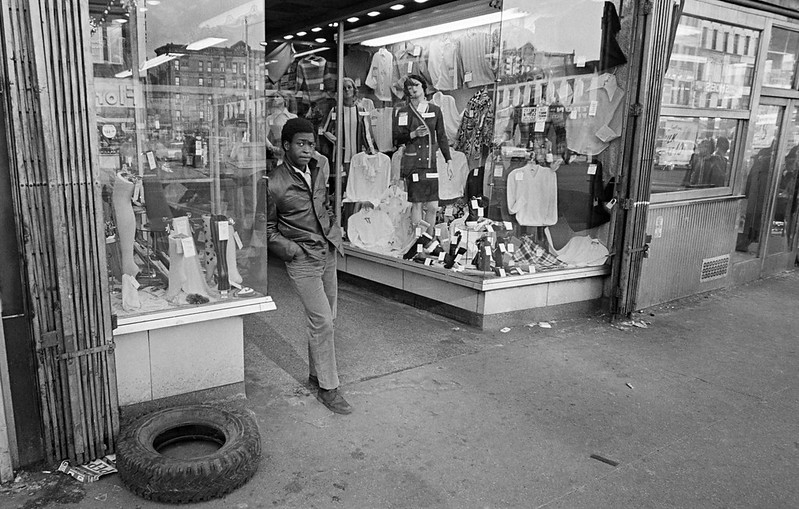

The novel focuses on the relationship between Tish and Fonny, two young African Americans living in Harlem, New York, in the early 1970s. Fonny is in prison, framed by a White cop for the rape of a Puerto Rican woman. Tish is pregnant with their child. The plot follows the efforts of Tish, her family, and Fonny’s father to prove Fonny’s innocence. Narrated by Tish from the first-person view, the story oscillates between present and past. It possesses a simple, but elegant and highly intimate quality. This narrative structure is employed, in differing ways, in all of Baldwin’s novels, apart from Another Country. We learn how Tish and Fonny met as children and how their love evolved. We find out who they are, get to know their families and their struggles against racial oppression.

If Beale Street Could Talk is a dense and highly complex work.

It weaves together topics around Black family life, institutionalized racism, gendered racial violence, intra- and interracial conflict, religion, and hypocrisy. What I want to focus on in this essay are the intersections between gender and race, and how they affect Black love.

The novel starts with Tish describing how she visits Fonny in prison; she tells him that she is pregnant. Fonny’s reaction is not exactly one of disbelief, but he struggles to internalize what Tish just told him. We witness the first instance of distance created between the two, enforced by his incarceration. Regardless of the deep trust and love between them, Fonny instinctively withdraws upon hearing the news of her pregnancy. “…he was far away from me now, all by himself. I waited for him to come back” (If Beale Street Could Talk, p. 4). He might be wondering how Tish can be pregnant, given that he is in prison. However, similar moments at other points in the novel indicate that it relates more to the experiential gulf caused by their gendered subjection to racism. But I will return to that in more detail later.

From the start, the novel creates a strong sense of how Tish and Fonny’s lives are disrupted by racial oppression.

A remark on their plans to get married at the beginning of the novel is a case in point:

“I should have said it already: we’re not married. That means more to him than it does to me, but I understand how he feels. We were going to get married, but then he went to jail.” (p. 5)

Racism has made it impossible for them to conform to norms of propriety around marriage and childbirth. This adds even more social stigma to their relationship. This constant disruption of Black life is a guiding motif of the novel and defines their struggle to prove Fonny’s innocence.

Numerous obstacles arise over the course of the novel, making their efforts to free Fonny seem impossible. Daniel, an old friend of Fonny’s, could provide him with an alibi. However, he is also arrested on false charges and pressured to change his testimony. Victoria Sanchez, survivor of the rape Fonny is framed for, has returned to Puerto Rico. This makes it much more difficult for Tish and her family to contact her. Then there are, of course, the day-to-day hardships and socio-economic struggles that Tish, her family, and Fonny’s father have to deal with. Tish’s pregnancy takes place in the midst of all this, epitomizing how the continuation of Black life is under constant threat:

“[I]t’s something, when you think about it, how many babies were brought into those places [in Harlem], with rats as big as cats, roaches the size of mice, splinters the size of a man’s finger, and somehow survived it.” (p. 27)

Black women, as the novel states quite explicitly, take up the central role in this fight for the reproduction of Black life. Both in the literal and in the cultural sense.

Women are represented as giving coherence to their families.

Women “somehow manage […] to get it all together, to hold everything together” (p. 18). The book is also acutely aware of how gender is ultimately a construct, and how women are forced into their social roles by patriarchal structures.

“…a woman is tremendously controlled by what the man’s imagination makes of her—literally, hour by hour, day by day; so she becomes a woman.” (p. 52)

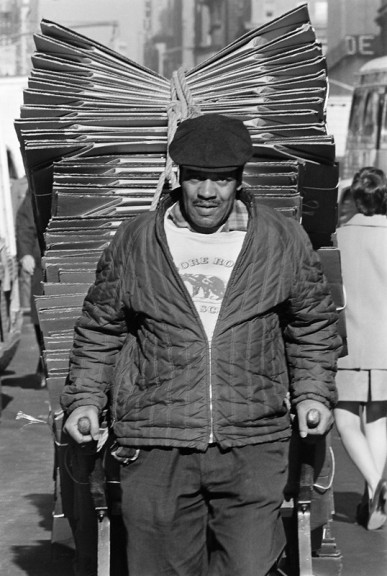

This intersection with race and racism further complicates gender relations in the novel. The Black male characters struggle with conforming to ideals of masculinity. Due to racial oppression, they suffer greatly from emasculation. This becomes most apparent with Fonny’s father, Frank. Frank used to own a tailor shop when Fonny and Tish were little. Due to the community’s decline of wealth and the resulting lack of customers, he went bankrupt and started working in a garment center.

The socio-economic status of African Americans did not improve after the 60s.

On the contrary, inequalities in income and wealth became even more pronounced since the early 70s. Fonny’s family depends increasingly on him to contribute extra income. Frank can not reconcile this with his desired self-image of the father as the provider. He begins to drink and spends more and more time at bars. In part, this also relates to the troubled relationship with his wife and two daughters. Fonny’s imprisonment then causes Frank to further doubt his capacities as a father and a man:

“I don’t know if I ever was any kind of father to him—any kind of real father—and now he’s in jail and it ain’t his fault and I don’t even know how I’m going to get him out. I’m sure one hell of a man.” (p. 109)

Tish’s father, Joseph, tries to console Frank and assures him that Fonny loves and admires him. It appears that the need to work even harder to provide for his family gives Frank some temporary purpose. In addition, later he needs to get the money together for Fonny’s bail. However, he learns that Fonny’s trial has been postponed because of the disappearance of Victoria Sanchez. After Tish’s mother, Sharon, travels to Puerto Rico and tries in vain to convince her to change her testimony, something inside of Frank breaks.

Another crucial moment in the novel exemplifies this racialized emasculation.

Fonny and Tish encounter the White policeman, Officer Bell, who is framing Fonny. Tish goes shopping in an Italian grocery store and is sexually harassed by another customer. Fonny, returning from buying cigarettes, sees that Tish is being molested, and beats up the aggressor. Bell comes running into the grocery store, accusing Fonny of starting the fight. Tish positions herself between him and Bell, acutely aware of how dangerous the situation is. The shopkeeper intervenes and confirms Tish’s story of being harassed, and Bell eventually retreats.

Moments later, Tish and Fonny walk back home and Fonny tells her that she should not have protected him. Evidently, he is furious, hurt, and deeply frustrated. He was unable to fulfill the role expected of men in American society. Instead of protecting Tish, he had to depend on her because of his Blackness. Irrespective of Fonny’s anger and pain being absolutely justified, this view of gender roles is highly problematic. It highlights the one aspect of the novel that I would criticize.

There exists a definite tension within the book.

On the one hand, it offers a critical perspective on gender relations and patriarchy. On the other, Fonny assumes that as the man, he necessarily has to assume the leading role. Tish naively acquiesces:

“And he suddenly takes the bag of tomatoes and smashes them against the nearest wall […]. I know what he is saying. I know he is right. I know I must not say anything. Thank God, he does not let go my hand.” (p. 122)

There are a few situations where Tish appears passive, willing to follow wherever Fonny leads. His domination is represented as benign. He always respects and cares about Tish’s wishes and feelings, and never intentionally hurts her. Nevertheless, the existence of a hierarchy between men and women is thereby still naturalized. Later, Fonny tries to apologize to Tish, acknowledging that she saved his life. However, he still argues that this was not how things were supposed to be.

He justifies his position with the constant threat of racial violence.

Fonny believes he has to protect her from it, and not the other way around. Still, the novel opens up a critical space for reflecting on norms of masculinity:

“[…] you can get very fucked-up, here, once you take seriously the notion that a man who is not afraid to trust his imagination (which is all that men have ever trusted) is effeminate.” (p. 52)

These opposing perspectives on gender and gender relations are never resolved.

And they might reflect Baldwin’s own limitations in thinking about these matters. Having said that, his representations of gender and its lived realities are still far ahead of most of his male contemporaries. If Beale Street Could Talk does not focus exclusively on the criminalization of Black males, their anger, and pain. It also seriously engages with the specific forms of gendered racism and racialized sexual violence experienced by women. The greatest weakness of the film adaption by Jenkins is that it does not achieve the same critical insight.

Apart from the harassment at the grocery store, Tish experiences racialized sexual violence at her workplace daily. She works at a shopping center, where she sells perfume. Tish describes how Black and White men interact with her in greatly different ways:

“[T]hey never smell the back of my hand: a black cat puts out his hand, and you spray it, and he carries the back of his own hand in his own nostrils. […] But a white man will carry your hand to his nostrils, he will hold it here.” (p. 101)

This transgression by White men, assuming the right to Black women’s bodies, is made more explicit between Tish and Bell.

On her way back from grocery shopping, Tish encounters Bell on the street, alone. She looks into Bell’s eyes and his gaze, heavy with a cruel lust for her, makes her feel debased and abused:

“I can still see us on that hurrying, crowded, twilight avenue, me with my package and my handbag, staring at him, he staring at me. I was suddenly his: a desolation entered me which I had never felt before. I watched his eyes, his moist, boyish, despairing lips, and felt his sex stiffening against me.” (p. 151)

The most prominent act of sexual violence in the novel is the rape of Victoria Sanchez.

For most of the book, the reader principally sees Victoria through the eyes of Tish and her family. They don’t understand why Victoria falsely identified Fonny. They regard her almost as a culprit. However, when Sharon travels to Puerto Rico to convince Victoria to change her testimony, a much more complex picture emerges. Sharon sees the abject poverty in which many Puerto Ricans, including Victoria, live. She comes to understand that African Americans and Puerto Ricans actually share a similar fate. Both are part of a marginalized and exploited global population. When she comes back to the U.S., Sharon contemplates:

“…they don’t look at the garbage dump. Like they don’t look at themselves—like we don’t look. I had never seen it like that before. Never. I don’t speak no Spanish and they don’t speak no English. But we on the same garbage dump. For the same reason.” (p. 162)

Sharon talks to Victoria, and it becomes clear that she is deeply traumatized. She was raped, apparently by a Black man. Fonny was the only Black man the police had in the lineup and she was pressured to pick him out. Sharon’s questioning triggers a mental breakdown in Victoria.

Sharon’s experiences in Puerto Rico and Victoria’s fate make visible the intersecting racist and sexist structures of oppression. While it is personal to Fonny, Tish, and their families, it has, in fact, a global dimension.

White supremacy chiefly works by veiling this fact and pitting marginalized groups against one another.

This leads me to the experiential gulf between Black men and women, created by the above-mentioned dynamics of gendered racism, and Black love. There are several instances where a distance appears between Tish and Fonny. But this becomes all the more pronounced over time. When Fonny learns that the trial has been postponed and that they cannot reach Victoria, Tish observes:

“He looks straight at me, into me. His eyes are enormous, deep and dark. I am both relieved and frightened. He has moved—not away from me: but he has moved. He is standing in a place where I am not.” (p. 167)

While their feelings for one another never appear to change, Tish and Fonny do.

They have experiences that they cannot share with the other; experiences that have a lasting and fundamental impact on them. Tish never tells Fonny about her encounter with Bell. Neither does Fonny tell her about his experiences in prison. The latter is almost certainly related to Fonny’s above-mentioned fear of dependency on Tish.

It is in light of the omnipresence of violence that Tish and Fonny’s love appears all the more powerful.

To love is daring, for opening oneself to another always means being vulnerable.

This becomes particularly dangerous in a racist, sexist, and capitalist society. Where exploiting others’ seeming weaknesses to maximize one’s gains, is seen as a virtue. Especially those who are considered inherently less. Then, to truly love another represents an act of resistance against the pathological, hegemonic view of social relations. It is in this sense that their love has a pronounced political dimension. The forced internalization of oneself as inferior, as the stigmatized Other, is one of the central mechanisms of racial domination. Love is fundamentally opposed to this. It teaches people that they deserve self-worth and dignity. White supremacy, therefore, seeks to thwart such deep and meaningful relationships among the oppressed. Tish and Fonny, however, found a center within themselves and each other and created a space that is their own.

Tish and Fonny hold onto love with all their strength, regardless of the obstacles they face.

They never stop fighting, never cease believing in one another. It is therein that we find the central message of the novel and of much of Baldwin’s work in general. The miracle of the grace and courage with which Black people have always struggled against seemingly indestructible forces of oppression:

“It demands great force and great cunning continually to assault the mighty and indifferent fortress of white supremacy as [Black people] in this county have done so long. It demands great spiritual resilience not to hate the hater whose foot is on your neck, and an even greater miracle of perception and charity not to teach your child to hate. The [Black] boys and girls who are facing mobs today come out of a long line of improbable aristocrats—the only genuine aristocrats this country has produced.” (The Fire Next Time, p. 99-100)

Raja-Léon Hamann, LeipGlo contributor and Ph.D. student in Cultural and Social Anthropology, offers his insights into the novels of James Baldwin in this article series. Have a look at his examination of Baldwin’s first, Go tell it on the Mountain.