Even amid today’s hyper-commercialized world of football, RB Leipzig stands out as something of a novelty. Their journey from the fifth tier of German football to Bundesliga runners-up in their debut season in the top-flight – along with reaching the Champions League Semi-Finals in 2020 – has been hailed as something of a fairy tale by observers outside of the country. However, there are few fairy tales that depict a “hero” in possession of a bottomless wallet to help effortlessly sweep away all adversity. Especially a bottomless wallet bequeathed by the same international corporation that created them, primarily as an innovative marketing project.

Indeed, confectionery company Red Bull GmBh’s creation of a team almost from scratch and in the corporation’s image is unparalleled, even amongst those European leagues already immersed in advertising logos and corporate identities.

The fact that RB Leipzig exists in Germany – where a club’s history, tradition, and identity are prized nearly as highly as titles – has caused a great deal of controversy and even given the team the mantle of “most hated club” in the country. Yet, despite the contempt the team inspires, the level of football on display contributes to a greater level of competition in a league otherwise dominated by just Borussia Dortmund and Bayern Munich.

The not so humble beginnings

Before the controversy, there was an Austrian entrepreneur desperate to include a top European team among his portfolio of sport franchises. Dietrich Mateschitz, co-founder and managing director of Red Bull GmbH, was already involved in football when he first entertained the idea of adding a German team to Red Bull’s roster in 2006, having acquired and re-branded clubs from Salzburg and New York.

From early on, the Eastern German city of Leipzig appeared to be the best location for the project.

No team from the city had competed in the Bundesliga since 1994, when a modern iteration of historical club VfB Leipzig spent one season there. There was also a newly-built stadium lying unused since the conclusion of the 2006 World Cup. The city itself was entering the initial stages of a renaissance, having stagnated in the aftermath of German reunification. The population was growing as large, international companies were beginning to set up operations, and this was accompanied by a flourishing cultural scene that led to the city being called “the new Berlin.”

However, Dietrich and Red Bull’s initial attempts to come to some agreement with an existing club – the financially ailing FC Sachsen Leipzig – were violently opposed by fans and subsequently abandoned.

They then briefly examined other potential lower-league clubs in the west of the country, before settling on creating an almost entirely new club in their original target city of Leipzig. However, to start completely from scratch would have required starting in the Kreisliga – the lowest division of the German football hierarchy. To navigate around this, Red Bull would need to get hold of the playing license of another club.

Preferably, this club would be outside of the remit of the German Football Association (DFB) so that the organization’s strict licensing laws would not apply to the new team. To this end, the new club purchased the playing license of fifth-tier minnows SSV Markranstädt, a team located 13km outside of Leipzig. In their inaugural season, they quickly secured promotion to the next tier, NOFV-Oberliga, and then moved into the city’s Zentralstadion (now renamed the Red Bull Arena).

The Roten Bullen (Red Bulls, the club’s nickname) march forward was halted the following year by a fourth-place finish. A major rehaul of the team and staff – one of many during the club’s early years – saw Ralf Rangnick assigned as sporting director. Rangnick had previously led FC Schalke 04 to a second-place Bundesliga finish as the team’s former coach, and his newest appointment clearly did the trick as RB Leipzig finished top of the league that season.

Danish center-forward Yussuf Poulsen was signed for the team in 2013, prior to their second consecutive promotion, which saw them reach the 2. Bundesliga. In a bid to record a third back-to-back promotion, the summer of 2014 saw the club open its wallet and bring in Lukas Klostermann and Marcel Sabitzer. Unfortunately, momentum stalled as the team finished the season in fifth place. However, after another spending binge that brought the likes of Willi Orban and Marcel Halstenberg onboard, RB Leipzig concluded their dash through the German football leagues: A 2-0 victory over Karlsruher SC in May 2016 did the trick and sent them into the Bundesliga.

In only seven seasons, RB Leipzig had gone from a newly founded, fifth-tier team to the first division.

From there, they went on to qualify for the Champions League after finishing in second place in their first season at the top of German domestic football, reached the quarter-finals of the UEFA Europa League, and established their presence as a German footballing powerhouse.

Corporation or football team?

Considering their blitz through the German leagues, it’s no wonder some observers outside Germany view RB Leipzig’s meteoric rise as something out of a fairy tale; a fresh, lower-league team recording back-to-back promotions to reach the top and hold its own amongst the nation’s biggest clubs. Naturally, such a romanticized version of events conveniently ignores the vast amounts of money (by German standards) thrown at the club to make it a success.

The millions of euros RB Leipzig spent in the 2014 summer transfer window as a 2. Bundesliga team amounted to the combined total of that spent by half of the teams in the division above.

This was almost matched during the next winter transfer window, when the club spent an additional 10 million euros – 10 times the amount spent by all the other Bundesliga 2. teams together. Consequently, few within Germany view RB Leipzig’s rise with the same rosy tint as, say, the world saw that of Leicester FC. Instead, RB Leipzig’s success is generally viewed as something abhorrent.

For many Germans, it represents the apex of the shameful commercialization of football.

It’s not even as though the team is just heavily associated with a brand or corporation. Rather, the football team’s identity is synonymous with the image of the brand, and the boundaries between the two blur to the point of non-existence.

RB Leipzig fans would retort that their team is not the first in Germany to be created by a corporation and march onto the field adorned with its corporate insignia. Bayer Leverkusen and VfB Wolfsburg are both hardly subtle about the respective significant roles that Bayer Pharmaceuticals and Volkswagen play in their identities. However, a fundamental difference exists between those two clubs and RB Leipzig: The former were both started as sports and football clubs for company employees, whereas the team’s detractors would argue that RB Leipzig is a marketing project first and a football team second.

The Roten Bullen have picked up the ire that was previously reserved for 1899 Hoffenheim, a team whose similarly speedy ascent through the German leagues was bankrolled by a software billionaire.

Although, in the eyes of German football fans, at least Hoffenheim has a long history going back to 1899 – whereas RB Leipzig doesn’t. Indeed, this corporatism and lack of an authentic background are not appreciated in a national league of clubs replete with histories going back a century.

Flouting tradition

Identity, history, and fan involvement are three fundamental elements of club-level football in Germany. The DFB has strict rules in place to protect these values and prevent mass commercialization, higher ticket prices, and a growing disconnect between club management and the fans seen in other major European leagues.

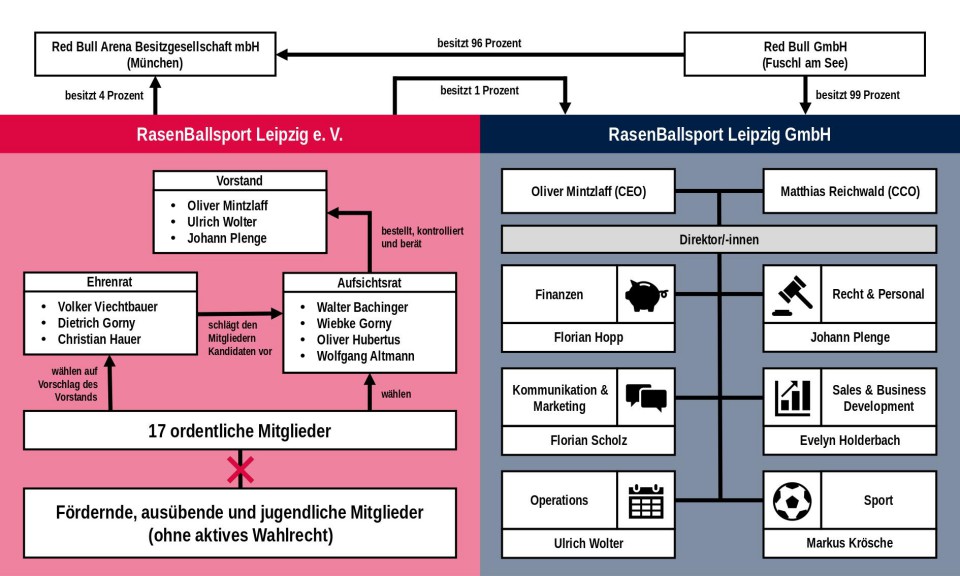

The methods RB Leipzig have utilized to twist these rules have therefore done little to endear the club to already critical German fans. Some accuse the club of making a mockery of those measures, and this is most evident in the way RB Leipzig has circumnavigated what is known as the 50+1 rule. All German football clubs are legally classified as social institutions, and the 50+1 rule, therefore, stipulates that the majority of voting rights must be held by the club’s fans.

In 2017, Bayern Munich had 290,000 such members who were able to vote for a new club president. RB Leipzig on the other hand had just 17 voting members, and all these members were people already employed by the club.

Further evidence of RB Leipzig’s legal chicanery, poking and prodding the boundaries of the DFB’s rules, is apparent with the team’s name. Licensing laws prevent a team from incorporating a brand name within its own name (Bayer Leverkusen being one of a few exceptions).

It is at this point that you, the reader, are dealt the revelation that the “RB” in RB Leipzig does not in fact stand for Red Bull.

It is actually an abbreviation of “Rasen Ballsport” (or in English “lawn ball sport”) and one that coincidently aligns with the initials of the energy drink company that owns the team. Such flagrant flouting of DFB rules such as these and the resulting reaction from fans have led the national media to dub the club “the most hated team in Germany,” as mentioned. This hatred is sometimes expressed in the way of violence towards fans. During an away match against Dynamo Dresden in August 2016, home fans unfolded a banner that said, “you can’t buy tradition.” Then, just in case their sentiments had not been made clear, a decapitated bull’s head was launched onto the pitch.

They aren’t all bad…

Any piece scrutinizing the less “authentic” aspects of the RB Leipzig experience should be fair and also acknowledge the undeniable positives that the team brings to German football. For instance, the lack of history and tradition spanning a century also means that the club is free of some of the negatives that such a heritage might bring. Heritage such as, let’s say, parts of an over-enthusiastic fanbase attacking opposing fans or throwing dismembered cattle onto the pitch during a game.

Home games certainly lack the same atmosphere found in other German stadia, with their ostentatious pyrotechnic displays and enormous, unfurled banners. However, the plus side is that they also lack the often accompanying drunken rowdiness and violence that mar other games. This makes games at the Red Bull Arena a more wholesome affair and one that can be enjoyed by the family without fear of getting caught up in trouble.

RB Leipzig also play indisputably good football. Their style is quick, young and aggressive, exhibiting all the attributes one would expect from one of the youngest teams in Germany.

That caliber of football on display isn’t just a benefit for fans of the Roten Bullen, but for all fans of the Bundesliga. While German fans are fearful at the thought of wealthy corporate benefactors running riot over the Bundesliga in the same way that they have in the English Premier League, it has at least had a positive impact on the competitiveness at the highest end of English football.

It can be argued that this investment prevented just one or two teams from dominating the league year in, year out, with their future dominance assured by the financial windfall they reap by their successive victories. For example, there have been five different EPL champions over the last decade. By comparison, there have just been two in the Bundesliga, with one of these (Bayern Munich) winning the league in eight of those years. If a team is able to make things more exciting by making the Bundesliga more competitive, is that such a bad thing?

Even so, regardless of the positives the RB Leipzig can offer, the very nature of the team, its corporate identity, and lack of history will ensure that it is a long time before the “RB Leipzig fairy-tale” is accepted by German fans.