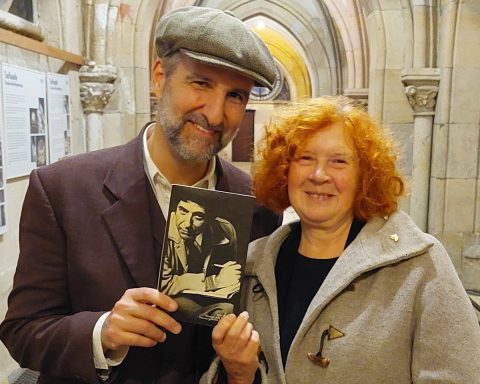

Conductor Vasily Petrenko is interviewed by Maximilian Georg

Vasily Petrenko was born, and received his training, in St. Petersburg, Russia. Since 2009, he has been based in Liverpool, UK, where he is chief conductor of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra. Throughout his career, he has conducted many other renowned orchestras. For his concerts and recordings, he has received a lot of acclaim and numerous awards.

On September 30th and October 1st and 2nd, he will conduct the Gewandhausorchester here in Leipzig with orchestral works and a piano concerto (8 pm, tickets still available). On September 23, he talked to the Leipzig Glocal about those concerts, the Corona situation, and more.

Maximilian Georg: The Leipzig Gewandhaus has just returned from the Corona break. How did you experience the lockdown when it suddenly started in March?

Vasily Petrenko: I experienced it in different countries. First, I was in Norway for the last series of concerts with me as chief conductor of Oslo Philharmonic. The program was The Rite of Spring. We had rehearsed it on Monday, and then on Tuesday in the morning just before the rehearsal, the country made the decision to go on total lockdown, banning almost every gathering.

We couldn’t do anything, so I left the country. I saw there would be no more flights very soon. It was sad, because everyone had been looking forward to those concerts.

Then I was in the Netherlands, where I did a series of concerts with the Rotterdam Philharmonic. The main piece was Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique. The concerts were full, but infection numbers were already starting to rise in the Netherlands. Still, we played all the concerts. On Sunday I left from Schiphol Airport, and when I landed I heard about the decision of the Dutch government to lock down the whole country. We had probably gotten to perform the very last concerts.

Then, here in Liverpool, we intended to perform Mahler’s 3rd Symphony, because we intend to do their whole cycle. But just before the first rehearsal, we heard about the UK lockdown. At that time, I would say that everywhere, in Norway, the Netherlands, the UK, people were expecting that it would take maybe some weeks, maybe some months but not more. Most were sure that by the summer, the virus would be gone, and countries would return to some kind of normality.

I wasn’t that optimistic to be honest. I was hoping for it, but already in March I saw that it would take a long, long time to reopen public venues, to be able to perform or gather.

What we have to do in every country is to increase the amount of tests. We have to test literally everyone. Public venues can serve as points for this. Then you can allow a certain number of people to go to concerts or theaters on the basis that all are tested negative on arrival. And there should be hygienic equipment such as disinfectant.

During lockdown, you conducted interviews with chief executives of various industries, talking for example about the ethics and productiveness of working digitally, remotely. In the performing arts industry, this way of working seems hardly possible. Musicians have to be in one place to play together.

I did several projects during the last months with the European Union Youth Orchestra as it was impossible to bring musicians from all over Europe together in one place. So we did a digital project, we did digital recordings. It is possible to record music in this way, but it requires much more rehearsing and recording time, and much more work by the conductor and sound engineer. It’s really miles away from just rehearsing face to face.

I guess the quality of the result cannot be the same.

Yes, it’s not the same, simply because everyone has different acoustics, and you feel that it has been treated. And there is this emotional coherence when everybody performs at the same time, whereas on the screen it’s everybody individually at home recording a musical fragment and then sending it.

They wear headphones?

Yes, you have a click track, there’s technology, but it’s not at all the same as when you are a group of musicians sharing the same emotions. Also for the public, watching a performance online via stream is not the same as sharing the emotions of someone who is next to you.

This sharing of emotions is an incredibly important part of human social life.

So for the music business it’s essential to be able to gather again.

Talking to musicians and managers around the world, I found that certain countries have a clear understanding of the value of culture and music. In Germany, for instance, classical music and classical culture in general is almost like an identity. All those German composers. That’s I guess for many Germans the identity of their souls.

So they will do everything to preserve this.

In other countries, it’s the same, in Russia with Tchaikovsky etc., in Finland with Sibelius. So in countries where you have this idea, they support, also now, their culture much better than in countries where it is seen as just a side idea, just a minor part of the economy. In my opinion, the impact of culture as an idea, a national one in the good sense, is underestimated. It can stitch a society together. Governments have to understand this more, and musicians have to get back to the concert stage.

So it depends to some extent on the country, whether we can be optimistic about the future of the performing arts?

I think they will survive. But I would encourage every government to give immediate support to culture; not just music but all arts; museums, architecture, literature, musicals, anything. A lot of their institutions have existed for hundreds of years, and if you don’t support them now, they may disappear, and then it’s the whole legacy of a country that is gone. I’m not saying you should spend gazillions of money on it now, but you should acknowledge that a lot of people have lost their salary.

For instance, here in the UK, according to a survey from last week, up to 40 % of musicians are either considering or are already changing their profession. In Sweden, one third of musicians are considering the same thing.

Already before the crisis, most musicians had a tough life, economically.

I always say, if you invest in culture, you invest in the future. It’s a long-term investment that will bring revenue back within 20 years in the form of a better workforce and society, less crime, better health, better education. But for 20 years, you won’t see those results, only afterwards. The problem is that political elections are every four years.

Coming to your concerts in Leipzig: You will conduct here three days in a row. What is your connection with Leipzig, is there anything special?

The first time I came here was in the late 1980s, when Leipzig was still in the GDR. I studied at a Boys’ Capella School in Leningrad (St. Petersburg). When Perestroika happened and the Iron Curtain was opened (before it came down completely), we were so much on demand to go West with the choir that we spent a lot of time in Germany in particular, in both parts at the time.

It was very interesting to compare the German Democratic Republic and the Federal Republic of Germany. Crossing the border in Berlin, going from the East to the West of the city. You saw differences and similarities, and you kind of sensed that both parts would like to be together, but it had not yet happened.

Since then I have returned to Leipzig several times. The last time was one or two years ago with the Gewandhausorchester. It’s one of the greatest orchestras in Europe and the world. For me, it’s always a pleasure to come back.

The program we are playing this time is actually very challenging. Especially Bartók but also Kodály are not easy for the string players. After quite a long period where no orchestra could play, I’m curious to see how this has affected us.

Were you involved in the selection of the pieces?

Yes, we went into that territory as we had to choose the right program for the current situation, because, as you know, not everything is possible (because of the limited number of musicians allowed on stage and the distance they have to keep between each other).

I love both Bartók and Kodály, and Shostakovich is of course one of my favorite composers. So I’m expecting a great week, and I had a very good connection with the orchestra last time.

It just clicked between them and me, which doesn’t always happen.

When you are in a city for a concert, do you have time to visit it?

Yes, between the rehearsals or afterwards I usually walk around. Last time I was in Leipzig I was surprised how many famous people, writers, artists, composers lived in the city in the course of its history.

Everybody knows about Bach, but when you walk around the city center almost every corner has a memorial about someone who did something here or there. Mahler for instance.

You can still visit the apartments of Mendelssohn and Schumann as well.

Leipzig was probably one the richest and most important cities for quite a long period of European history. I don’t think there are many other places with the same number of creative people living in the same city for such a long period in total.

On your list of recordings I saw that you have recorded many works by Russian composers such as Shostakovich and Tchaikovsky, but you’ve also conducted many others. Do you have any favorite composers or pieces? You’ve already mentioned Shostakovich.

There are so many of them. We are extremely lucky as performers because over the last 300 years so much music has been written for us. I discovered some works from the 1920s and 30s only recently, pieces by Hindemith or Respighi, for instance. So every day brings a discovery. This year, I was supposed to do two full cycles of Mahler, and of course a lot of Beethoven for his 250th birthday. Mahler sadly is not happening, but I can still do some Beethoven. One week after Leipzig, in Moscow, for the first time I will do the Große Fuge for orchestra, one of Beethoven’s very last works, which is one of the most difficult pieces for string players, I think.

It has never been performed in Moscow before?

It has probably been done as a quartet, but not in the full string orchestra version, and that’s what I’m planning to do. My latest recordings are Strauss and Stravinsky. I also have a passion for English music: We have done Elgar symphonies, and now William Walton is on the agenda.

And I have to say that from six or seven years onwards, when I first studied music, I’ve always been very curious about and perceptive to any composition and any composer. Over time, when you grow up, get older, your taste can change slightly, but a piece of music that I hate – I can’t name it, I can’t even imagine it.

You only maybe dislike some pieces?

I must say that what I have probably less of a taste for is music based on purely mathematical skills.

When it’s calculated.

You know, Schönberg was a genius, with the dodecaphonic system, and what he was writing was incredible music. But then there were so many followers, and for some of them it became a kind of idea or fetish to just write something dodecaphonic or serial.

And then you think, hey, music is initially about emotions, not about digits and numbers.

Otherwise a computer could write music.

That’s very interesting, because when I studied in Leningrad there was one of the first computers. We also studied solfeggio, and part of the training was a dictation, where the teacher plays something you don’t know and you have to immediately write down the notes. When a human plays, it’s possible, it just requires some time, and your attention and skill. But then they had the idea to take the education even further: They put a program in the machine to write a set of dictations, and that was one of the most complicated things I’ve ever tried to write down, because there is no human logic.

To me, music, even in the most complex pieces, remains an emotional message, a message that can be understood without knowing any other language.

Do you also go to concerts of other conductors? Do you draw inspiration from them or is there even an exchange with colleagues on a regular basis?

When I have a chance, I go to concerts. During the last months, I of course watched a lot on TV and digital platforms. But I always learn. I think the profession of conductor is lifelong learning; you learn on an everyday basis. In every performance you try to surpass yourself, it’s a constant process of perfecting. But you can only achieve it by looking at other people’s experiences and combining it with your own.

I also go to museums as often as I can and try to watch theatre plays, whatever enriches your life. I don’t just want to sit over scores all the time; I have to do this often enough anyway.

I imagine that in your position as conductor, you are somewhat lonely. Musicians have other musicians in the orchestra who play the same instrument, but you’re the one and only conductor.

It depends on the relationship between the conductor and the orchestra. I think it has to be based on mutual respect.

I do respect, honestly and sincerely, every musician in the orchestra, for the simple fact that I cannot play the instruments at the level they do.

The other simple fact is that the baton itself does not make any sound. It’s the orchestra that plays. So my role is to help them perform this or that piece of music in the best possible manner, the closest to what we imagine the composer had in mind. At the same time, the musicians should respect the conductor as a leader instead of fearing him or being afraid of him.

Mutual respect brings the best results. Off the stage, in normal life, I don’t see any problems with socializing. We are all humans, despite different jobs, and to me it’s important to stay human. I don’t want to be someone on a pedestal whom everybody worships.

Final question: Although you’re “only” 44 years old, you’ve already had a long career, since you started conducting at age 18. You’ve already achieved a lot of amazing things. Next year, you will join the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in London as music director. What else would you like to achieve in the long run? Is there a certain orchestra you’d one day like to conduct, or do you have certain long-term musical goals?

I would love to perform even more in Germany. I already go from time to time. This autumn there is Leipzig and Dresden, later also Munich, Berlin and other cities. But I probably haven’t done enough in Germany.

I also feel that I’ve started in many ways as an opera conductor, but then for the last years, I just haven’t been able to do much opera. In the future, I’d like to do more there as well. That’s one of the reasons why I have decided to be chief conductor only in one orchestra from next year onwards, because it will give me more space for guest-conducting, and also for the opera. And there are many more things, regarding recordings, regarding all areas. I think, you are actually right, I’m just 44, there still are many things for me to do.

There have been conductors still active at age 90.

There’s this myth that conductors live longer. The reality is just that those who live long become famous. For conductors, the journey to success is much longer. For soloists – when they are young, they perform very often, people hear them and everybody immediately understands: that’s a star, that’s incredible.

For conductors, the biggest achievement is what happens with the orchestra where they are chief conductors. In my case, I have been here in Liverpool for 15 years, and only now the recognition is coming.

Because the art of the conductor is less obvious.

Exactly. And those who pass away early, like recently Yakov Kreizberg at age 51 – he was a great and well-established conductor, in Amsterdam and elsewhere, but in the future not many people may remember him. I have many plans, not just in London but everywhere else.

A very important part of my life is the work with young musicians, to help them, especially now. I think this will be even more important in the upcoming years.

The European Union Youth Orchestra, already mentioned, is one of the few examples where Europe can work together, on a good basis and with a good result for everyone. So I hope this project will develop even further because that’s what we need. Similarly, I try to work with youths in Russia.

When I was 18, starting to conduct professionally, I started to make a list of the compositions I would like to conduct, at least in my near future. (The list already stopped at letter K in the alphabet because that was the end of three pages.) Since then, I have been doing a lot of concerts. However, all my life may not be enough to perform everything I would like to. I haven’t kept the list, and I don’t mark what I have done and what not, but there’s still so many wishes, so many things to do, so many important things to bring to the audience.

In fact, we are there for the people. That’s something people sometimes forget. We are there to make peoples’ lives better individually and collectively.

That’s our duty, our mission. That’s what we were born and educated for. So this time is even more desperate because we can’t do it. But we have the huge wish to do it again in the future, and we’ll hopefully do it next week in Leipzig.

Vasily, thanks again for joining us today! I wish you the best of success for the concerts in Leipzig and for your projects and career in general!