The German Democratic Republic (GDR) can be described in many ways. We have heard from a former member of the then-ruling Socialist Unity Party (SED) and from a historian. We can also ask people from all over the world what they think happened during all those years in the former East German state. However, we are never going to know what it was really like to live in the GDR without asking residents about their routine.

How do former GDR residents remember life before the Peaceful Revolution?

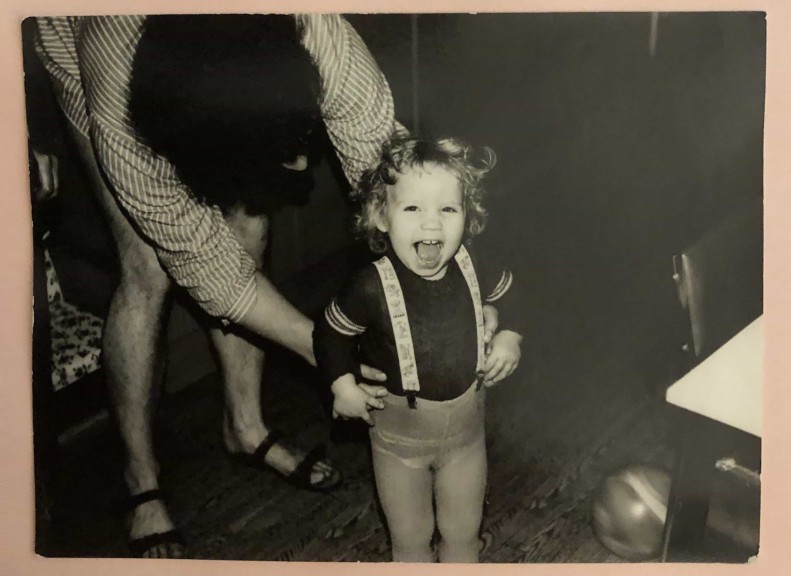

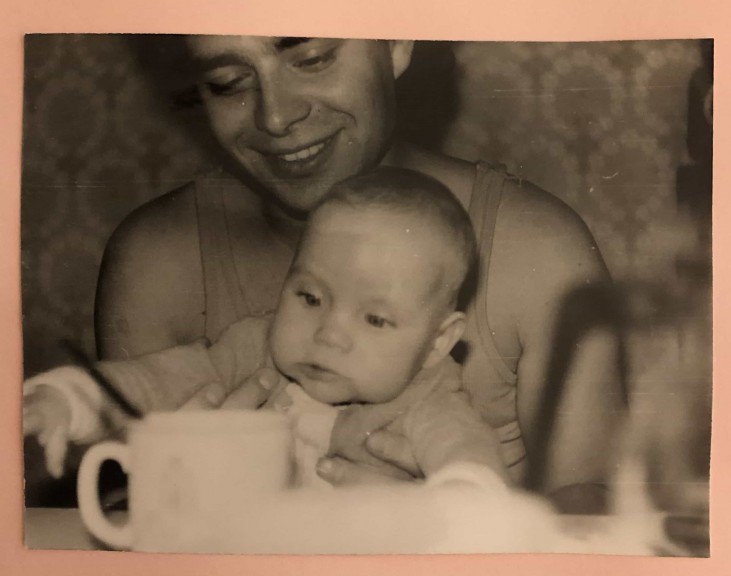

As part of our series on the 30 years since the Peaceful Revolution, and in commemoration of German Unity Day, we have talked to a father and daughter who were both born in the GDR and continued in Leipzig after Reunification. Here Michael and Anne Dietrich share their knowledge of and experience living in the GDR, as well as how the Peaceful Revolution happened from their perspective.

Michael was born in 1959, in a small city about 50 kilometers away from Leipzig. He says his childhood was not the most comfortable financially. His single mother had to work more than the average person to bring food to the table. Life was not always easy, but it was the only one he knew, and it was generally all right. “Other than not being baptized and not having a father, I don’t see any other disadvantages during my own childhood in the GDR.”

Michael adds:

I remember very well the time before and after the revolution.

His daughter, Anne Dietrich, was born in 1983. She was about 6 years old when the Peaceful Revolution happened, so she doesn’t remember much of the event. She is, nevertheless, a historian with a focus on GDR history.

Here are a few memories of life in the GDR that stood out during our interview.

The army

Michael reminisces about his education in the former East German state.

“Normally, anyone who finished school was obligated to enlist themselves for one and a half years of military service. But if you wanted to be a ‘good comrade,’ you would enlist yourself for three years voluntarily.”

It was almost expected by the government and GDR residents that young men would voluntarily enlist for those three years. Then you could go to university and start your career – which was probably in a branch of the military as well.

Michael was lucky. He finished secondary school and went straight to university. He studied in the Technische Hochschule Leipzig, today’s HTWK, and started his work life in the early 80s.

How did he avoid the army? He had bad eyesight.

Work

Michael worked as an engineer initially on the Spezialbaukombinat Wasserbau Weimar (Special Water Engineering Construction Site in Weimar). After some years he was transferred to Markkleeberg, where he got to lead a group that consisted of more than 50 people. “A socialist leader,” as he himself states.

Michael moved with his family to Leipzig in 1984. Anne was one year old. They moved into a complex in Grünau.

Anne recalls: “It was mainly built for assembly workers. But it was also built for young families that did not have a place to live in the beginning of the 70s, or for people who were waiting for relocation.” The apartment was relatively big: about 110m2. They lived there for 10 years.

Work opportunities were good. People always had a job. In fact, people had Recht auf Arbeit (“right to work”), which could be just as well translated to Pflicht auf Arbeit (“duty to work”).

“As a matter of fact, people would be forced to work.” Michael remembers that if people did not show up to work, the police would pick them up at home and take them to work, whether they liked it or not.

In addition to that, the offices that organized who would earn which salary didn’t know the reality for most GDR residents. And that led to problems.

Housing

Living, however, was extremely cheap – from 0.80 DM to 1.20 DM per square meter. Michael was doing well. By the time of the Peaceful Revolution, he was earning about 1,200 DM per month. In comparison, pensioners would get about 300 DM a month, and secondary school teachers about 600 DM.

There were no private real state agencies in the GDR. The state set a price, which was normally very cheap. Because of this, private owners did not have a reason to renovate or improve their properties. That is why many buildings in the GDR were in the same circumstances found during the Second World War and were only renovated later on, after Reunification. People would nevertheless live in these ruined buildings.

“They would use sheets as a roof and simply live in those horrible conditions. That was their harsh reality,” remembers Michael.

The bathrooms

Apartments at the time did not have a bathroom. Those were in the middle of the stairway and were communal.

If the building you live in is a little older, you may have seen little doors that are always locked between each flight of steps. Those were the bathrooms that every resident in the building used.

Bathing was another story.

Sometimes, the buildings only had toilets and no place to clean oneself. The Stadtbad (town bathhouse), such as the Leipziger Stadtbad in Eutrizscher Straße, was the place to get squeaky clean.

Connections

“When someone was crafty and had good connections, they could improve their quality of life drastically,” recounts Anne. In a nutshell, if you wanted to have good stuff, you had to know people and make connections.

Michael discloses: “I knew someone and because of that, I could get myself a washing machine, I could get my mother one, and one for my mother-in-law as well.”

Bananas were a treasure. They were a sign of power and progress in West Germany, which made GDR residents want it even more. However, not everyone had access to the tropical fruit. In fact, most people did not. Having it at home meant you were well off. Opulence at its best.

Cars were another problem. Going to an automobile shop and picking the car that best suits your lifestyle, paying for it and driving it away was not a reality in the GDR. In order to get a new car, you had to apply for it and wait for years to get it. It was easier to buy it used; but then, people would sell it for double or triple its original price.

Michael had a car, thanks to Uncle Albert. He was Michael’s father-in-law’s uncle. He sold his car to Michael on a “family price.”

There was even a black market for musical instruments. You could get whatever you wanted… for the right price. Usually used instruments from the West were sold at a ridiculously high price. Whoever could get their hands on those beauties had status.

Dos and don’ts

The GDR had to, until the end, pay reparations to the Soviet Union. This was made in a number of ways. For starters, all of the natural resources to be found in East Germany were considered to be the property of the Soviet Union.

Wismut AG was a mining company that had its main office in Chemnitz. It was the largest uranium producer of all the USSR-controlled locations. All of the material that was extracted from it was given to the Soviet Union.

The Sowjetische Aktiengesellschaft, or Soviet Joint Stock Company, was the department responsible for covering the reparations. On top of the payments, “we could never produce anything that could potentially start a war again,” Michael declares.

That meant no weapons, no tanks, and of course, no airplanes.

The revolution

Michael was not one of the protesters. He was too involved in his work.

He recalls: “On October 8th, Sunday, early morning, the telephone rang. It was someone from work. They told me I had to dress up, someone was coming to pick me up.”

I was brought to a meeting from the SED. There, people told me that on the next day, October 9th, there were going to be demonstrations, the police would be armed and there was an order to shoot. They told us that we should avoid going to the city center.

We know what happened. No one was shot.

“But no one knew it was a ‘peaceful revolution,’ says Anne. “The police could have shot. They could have taken the Chinese route.”

Michael adds: “I went to the SED office on the 10th. Everything and everyone was gone.”

And after?

What was most terrifying of it all was that GDR residents didn’t know what was to come. What would happen to their jobs and ways of life?

Michael was lucky (once again). The company he worked for was one of the few that remained after the revolution. Most people did not have this opportunity. From October 1989 to the mid-1990, most people would go away; their favorite destination was West Germany.

“It was sad, what happened. You can see the results in Leipzig: it was an industrial city,” remembers Michael.

Among the positives that came out of the revolution were cleaner air and water, though.

“Whoever looks at Leipzig now cannot even fathom how dirty Leipzig looked,” says Anne. Before the revolution, the air and water quality were very low. Pollution was extremely high. All because of the chemical plants.

But the negative aspects of Reunification also matter. Most qualified and educated people went to West Germany. Nearly all industries and companies closed. The result was mass unemployment, and a socioeconomic divide that persists to this day.

“Ossis” vs. “Wessis”

In order to fill in the gap of socialist politicians, the government in the West sent its people (“Wessis”) to the East. As Anne remarked:

In Leipzig, we could see it very well. Since the beginning, western politicians favored Leipzig to occupy certain positions within the government.

So western politicians – who did not know about the local culture, habits and needs – were governing over East Germans (“Ossis”). Actually, West Germany was full of false, and sometimes dumb, preconceptions of former GDR residents such as Anne:

“I had an experience with people who judged me because I am from the East. I interned in the West, in Düsseldorf in the early 2000s, and I never thought this would happen to me. Mainly because it was so many years after Reunification. I thought people would have forgotten about it. But they would make fun of me. They would tell clichés, like the ‘dumb Ossis.’ Or the typical joke with the bananas.”

That period of history was a crucial moment for everyone in Germany, with ripples spreading to the rest of the world. We hope that with this, you can better understand how everything happened also in people’s everyday lives, and why we should keep the nuances in mind.

Our series will continue until next week, as the Peaceful Revolution commemorations culminate on October 9th. Lichtfest in Leipzig will be special this year.

The original interview with Michael and Anne Dietrich was in German and all quotes have been translated into English.