Chris Gaida and I met by chance at the “Speak with me” series at the Museum für bildende Künste in Leipzig, where every second Wednesday of the month women from different countries come together to talk to each other about art. The round always starts with self-presentations, and so I found out that my neighbor moved from the BRD (West Germany) to the GDR (East Germany) in 1988.

Now this piqued my curiosity, since it was so exceptional. The usual migration attempts went the other way around.

The GDR citizens unable to bear the authoritarian rule or lack of basic life necessities and comforts were very inventive about constructing their means of escape.

Their enterprise had to be kept secret from everybody, since the chances of being denounced were very high and they risked not just being brandmarked as traitors, but persecuted and imprisoned. Up until the mid-1960s, about a thousand people a year tried to escape; and although new obstacles and barriers were put in place after that, still about 120 people a year tried their luck.

Failed escape attempts claimed many lives as border soldiers had orders to shoot the fleeing people, and the area leading up to the Berlin Wall was partially mined. Also regular border guards were notorious. GDR citizens and tourists alike trembled at the mere thought of an encounter with them and their vicious dogs.

I start on purpose with these facts because they underline how exceptional Chris is. In our interview, she said:

I wanted to live my dream.

Her dream was that of security and equality. As a young girl, she read Gorky and she saw how poor people in West Berlin were, their housing run down and unhealthy. During frequent family and Evangelical community visits to East Germany, she saw the opposite.

When she was 22, an unemployed mother, she decided to move to the GDR, where by the simple feat of being able to send her child to nursery school and kindergarten, and claim the constitutionally guaranteed rights to education and work, she would pursue occupational studies and get a good job. So she cancelled her electricity and phone contracts, found the only firm that transported furniture to the GDR, left her furniture in a basement for the firm to pick up, and – after a brief visit of the West German intelligence officer who wanted to know whether she knew what she was doing – crossed the border.

She and her child spent barely two weeks in an Aufnahmelager (“reception camp”), where everything was provided for, including playgrounds, kindergarten and school for children, and food, health and entertainment facilities for everybody. There were a total of three such camps in the GDR at the time. “Hers” was excellent; she does not know about others.

There, Chris met many returning former GDR citizens who had gone to the West and were now back.

Everybody was subject to health and security checks at the camp. In her case, a “Christmas amnesty” put a quick end to her explorations of the camp facilities. And then it did not take long before she could “live her dream.”

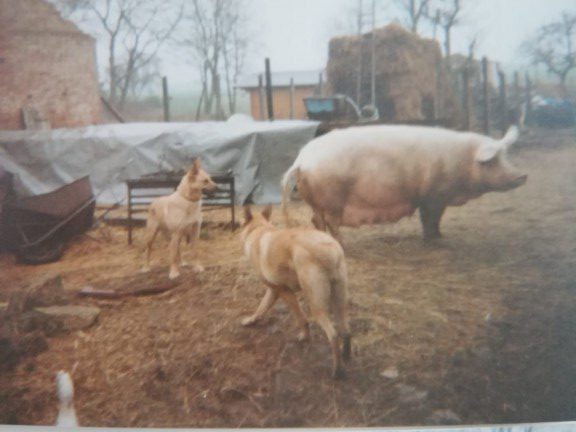

After a brief stay in her future in-laws’ apartment, she moved up to Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, where she became a member of an state-owned agricultural cooperative. She lived in a small village, milked the cows, fed the ducks, and devoted herself with enthusiasm to other typical agricultural chores. The man she was in love with was a specialist the cooperative did not want to lose, so it offered them a house.

Perhaps, she speculated, it was different in big factories down in the center or southern of East Germany, but up there where she lived, workers said what they thought. This contrasted strongly to West Germany as she had known it.

Chris had never had much respect for authority, and enjoyed that the boss there could get a “no” for an answer, like when he wanted somebody from the crew to put in an extra day. And one got paid for extra hours!

She wanted to live a simple life, the kind the Green Party advocated for. Her family and neighbors were much more materialistic than she was. In contrast to her, they spent a lot of time on finding and acquiring material goods. For her, it was more important that culture was on a high level. And yet, says Chris, “my family came very often for a visit to us. They loved the farm.”

She kept telling them how expensive apartments in the BRD were, but they would not believe her. The family of her husband did not find her jokes funny; for them, the Western standard of working and living – Western “welfare” – was a holy cow. She, on the other hand, found it simply “cool” that one still had the horses work the fields.

People in her surroundings wanted a Schnitzel every day, while she was happy about fresh berries, apples, pears and plums. When the time of the Peaceful Revolution came, there were many discussions: some wanted to keep the GDR but reformed, others wanted reunification. Her family “chose the banana.”

What she definitely did not like was the spying system and the widespread alcoholism in East Germany then.

Alcohol made it easier to subdue the memories and to come to terms with reality, to remain “brave and disciplined –

German.” People’s problem was not so much burnout as “bored out.”

It took Chris a while to realize that people lived in fear of repression. The older people remembered or experienced it – still feeling its mark decades later, constantly warning their children not to speak their minds, so that they could avoid a similar fate of sanctions that would put an end to one’s life chances once for all.

People did speak up about problems, like tool or commodity shortages. In the best case, there was an improvement. In the worst case, nothing happened. But she remembers there being no repression in that sense.

Chris has found it good – she did then and she does today – that welfare be equally distributed.

For her, from the moment she moved to the little village and into a house the cooperative offered her and her husband, “the GDR soldiers were the ones who protected me. I felt like a GDR citizen should have felt. I was a ‘model GDR citizen.'”

For her, the men in power were little men whom one did not need to fear:

I lived in a bubble of my private life. I was all set up and all went well.

Only after a while did she become aware of silence.

People in the village talked about and knew much about each other; the private sphere hardly existed. The best was this one woman, the “village newspaper” – she knew everything, past or present, and generously shared it with everybody. However – and that is where state repression dictated limits – people did not talk, not even to their family

members, about their relationship or experiences with the state.

Only much, much later did Chris realize that apartments differed in their size and quality, and that distribution was skewed in the GDR. Only later did she see how the elite lived and the shops they had.

When the Peaceful Revolution began in 1989, Chris was not quite aware of the danger associated with demonstrating in the repressive GDR. Nor of the risks taken by speakers who addressed the shortcomings of the GDR to call for reforms.

Towards the end of 1990, demonstrators stopped calling out “Wir sind das Volk” and switched to “Wir sind ein Volk” – that is, stopped asserting themselves against the GDR elites and started calling for reunification. Similar divisions surfaced in her little village. She was for reforms and against the Reunification, but belonged to a minority.

For Chris, one funny aspect of the Reunification was that “I was treated like a model Ossi; people wanted to hug and to free me – which I did not want. The other was my cousin who loaded his car with bananas and mandarins and wanted to drive up to bestow this gift on my village. Only he ran out of gas and was headed for the wrong village anyhow, so he ended up distributing bananas and mandarins much short of his goal.”

In her view, the Reunification proved her right.

The borders, the GDR soldiers protecting her and the GDR being gone, there is no protection against poverty. Capitalism started swallowing firms, houses, jobs.

She still finds it unjust that some people are extremely rich and others are poor. After the Reunification, some people made it, but many went under.

Chris studied Heilerziehungspflege (“healing pedagogy”) and was involved in building up a new program offering advice to teachers and parents about how to make the life of handicapped children more comfortable by, among other things, putting only realistic demands on them. She has contributed to a less authoritarian teaching and parenting style.

She has since left the Klein Welzin farm. Her new Leipzig apartment was built only a couple of years ago. From her balcony, she can see nearly all of Leipzig’s towers.

Still, Chris thinks of herself as a GDR citizen and misses “living her dream.”