There are certain excursions or trips that open your mind. Within a few days you learn a lot – as it happened to me with a short trip to Lübeck. As a bonus, it was November and the city was preparing for Christmas, with shop windows and lights and all the good things that come with the holidays.

The city is known for its marzipan, the famous almond sweet originating in Persia. There is a famous patisserie (Niederegger) that makes it and sells it all over Germany. Its shop windows were decorated with figures from fairy tales made of marzipan.

This happened to be the last trip I made before the virus closed down all roads and borders.

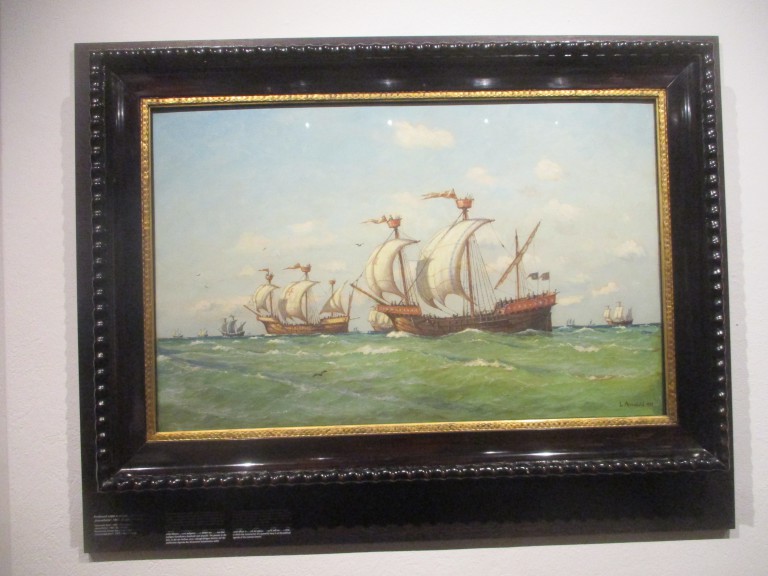

Lübeck is a small and lovely town by the Baltic Sea. It has beautiful houses which remind one of the Netherlands. It also has canals and a naval history spanning many centuries. Lübeck was one of the most important cities of the Hanseatic League (or Hansa).

The Hansa Museum, one of the most beautiful I have ever visited, tells the story of the creation of this commercial partnership that was established in 1241 by the cities of Lübeck and Hamburg, and which soon came to include many more cities not only in Germany but also in Belgium and other European countries. Like many other similar museums, the Hansa Museum is made largely for children, following good educational methods. But this amazing museum also manages to enchant and teach adults.

There, we learned details about the life of the patricians and got to know the typical ships of the region, the kogge, which exported beer to Russia and imported furs from there. We listened to audio conversations on the subject of bargains based on true reports between traders and customers of the Bruges market (in a special room set up in every detail).

We wandered around the time of the plague in awe and terror and learnt how people at that time began to make wills and donate their valuable objects to monasteries in the hope of saving their souls. In fact, because the monks did not open the doors for fear of getting infected, the ill threw their precious belongings and their jewelry over the monastery’s fences.

Hometown of Thomas Mann, Lübeck also has the Buddenbrookhaus, from his Nobel-Prize-winning novel Buddenbrooks (1901).

The house belonged to the author’s grandmother. It has been turned into a museum dedicated to Thomas Mann and his brother, Heinrich Mann, also a writer.

Thomas Mann is actually the first of three Nobel laureates Lübeck boasts, having nabbed the Literature prize in 1929. The second is iconic politician Willy Brandt, awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1971. Finally, in 1999, Günter Grass – a writer and artist who was born in Danzig (Gdansk) and died in Lübeck – got the city’s second Nobel Prize in Literature and third overall. Their respective houses each have their own museum in town.

Lübeck also wows visitors with its churches. In the crypt of the Sacred Heart Church there is a monument to the four local martyrs who resisted the Nazis and were executed. Three of them – Johannes Prassek, Eduard Müller and Hermann Lange – were Catholic priests, and one, Karl Friedrich Stellbrink, was an Evangelical-Lutheran pastor. In the crypt, their robes and other personal items are preserved, and there is interesting information about their life and death.

But perhaps the most impressive sight in Lübeck is the 13th-14th century Marienkirche, a church severely damaged during the bombings of World War II.

The organ on which Buxtehude played was destroyed. In order to listen to this composer, Bach is rumored to have crossed 400 kilometres on foot from Arnstadt, where he lived, to go to Lübeck. The amazing painting Totentanz (Danse Macabre) of 1463 – which told in verses and pictures the story of the merciless Plague – also fell victim to the bombs.

It was a work inspired by a similar French one. Its artistic value was great and the residents of Lübeck, fearing that it would go up in flames, protected it with a special thick wooden casing. But the British bombs, which fell on Lübeck in 1942, were different from those expected by the inhabitants, and the artwork was destroyed even faster.

Today, only one photograph of the Totentanz survives. There is a similar artwork in Tallinn, Estonia, smaller than that of Lübeck.

Death comes to put them all in the dance, says the story from the painting.

The emperor, the bishop, the peasant, the rich, the poor, the old, the young. They all find excuses to avoid the danse macabre, or “the dance of death.”

For example, the farmer says that he does not know how to dance. He spent his whole life working hard to get a good harvest. Death, however, does not accept their statements. And he moves on to the next one, whom he asks to dance with him.

I didn’t know it then, but strangely this work of art prepared me somehow psychologically for the coming pandemic. This short trip to Lübeck was surely an unforgettable experience and has now taken a unique dimension in my mind.