“Lucky he who was taught history,“ as the saying I remember from my school years goes. I thought it was attributed to Plutarch, but my internet search offers up the name of Euripides. Well, I was a very negligent pupil, so I wouldn’t know. And because I was so negligent, today I regret not having learned history. Or maybe I was like Jane Austen, who wrote in Northanger Abbey:

“I read it [history] a little as a duty, but it tells me nothing that does not either vex or weary me. The quarrels of popes and kings, with wars or pestilences, in every page; the men all so good for nothing, and hardly any women at all — it is very tiresome: and yet I often think it odd that it should be so dull, for a great deal of it must be invention.”

How can one disagree with Jane Austen, even if one is not a woman? Men wrote history. Accustomed by nature to hunting and fighting, they have maintained through the centuries their often violent and expansive character. Even today, when they do not have to kill wildlife in order to secure their daily food. The book and poem presented here are not the least bit boring. They do, however, make us rethink: why so much pain, so much destruction, so many dead, so many wounded, so many prisoners?

How can one disagree with Plutarch or Euripides? The lucky ones who have learned history will probably be wise enough not to repeat it. The peaceful nature of such wise people will be appalled when they read the true story of Sergeant Bourgogne. And the poem, “Leipzig”, by Thomas Hardy, which is about the Battle of the Nations which took place in Leipzig in 1813. For those of us living in this city, there will also be familiar names of places and people, like Lindenau and Poniatowski.

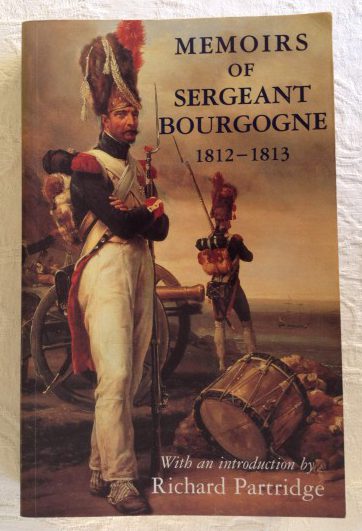

The Memoirs of Sergeant Bourgogne is the diary of a French soldier during and after the 1812 campaign in Russia.

It is an unique documentation by an eyewitness which narrates the capture of Moscow, the retreat, and the many battles which followed. Finally, it recounts the return of the decimated army to the homeland after an odyssey beyond imagining.

Courage, ingenuity, and incredible amounts of luck are the main elements of Bourgogne’s memoirs. Lots of horse meat, many corpses, people dying on every page. It doesn’t sound appealing and yet it is a very interesting read, written by a human being about the most inhumane experiences.

“I cannot possibly describe all the sufferings, anguish, and scenes of desolation I had seen and passed through, nor those which I was fated still to see and endure; they left deep and terrible memories, which I have never forgotten”.

“For the honour of humanity, perhaps, I ought not to describe all these scenes of horror, but I have determined to write down all I saw. I cannot do otherwise, and, besides, all these things have taken such possession of my mind that I think if I write them down they will cease to trouble me. And if in this disastrous campaign acts of infamy were committed, there were noble actions, too, which do honour to our humanity; amongst others, I have seen men carry a wounded officer on their shoulders for many days.”

Napoleon’s soldiers were driven mad by fatigue, by exhaustion.

Their comrades could tell that their end was near when some were seized by “the laughter of death.” In the midst of all the hardships, however, there was terrible self-sacrifice towards their weakest companions. Most had followed Napoleon in all his campaigns, and they nurtured an incredible adoration for their leader.

One of these men was M. Mellé, a Dragoon of the Guards. Bourgogne had often met him during the retreat, leading his horse, and making holes in the ice of the lakes to let him drink. He was from Condé, the place Bourgogne himself was from. According to Bourgogne, “before entering the Guard, M. Mellé had already gone through the Italian campaign. With the same weapons and the same horse, he went through the campaigns of 1806 and 1807 in Prussia and Poland. Then those of 1808 in Spain, 1809 in Germany, 1810 and 1811 in Spain, 1812 in Russia, 1813 in Saxony, and 1814 in France.”

These were tough eternal soldiers who died shouting, “Long live Napoleon!”

Military professionals who later, desperate for employment, fought on the side of the Greeks for liberation from Ottoman rule. But also on the side of the Ottoman oppressor, some as mercenaries.

The cold, the snow, amidst hunger and disease, full of fear, is described brilliantly by Adrien Jean-Baptiste François Bourgogne, the son of a cloth merchant from Condé-sur-Escaut. There are some moving stories, such as that of Mouton, the dog following the regiment.

“Mouton had been with us since 1808. We found him in Spain, near the Bonaventura, on the banks of a river where the English had cut the bridge. He came with us to Germany. In 1809 he assisted at the battles of Essling and Wagram; afterward, he returned to Spain in 1810-11. He left with the Regiment for Russia; but in Saxony he was lost, or perhaps stolen, for Mouton was a handsome poodle. Ten days after our arrival in Moscow we were immensely surprised at seeing him again. A detachment composed of fifteen men had left Paris some days after our departure to rejoin the regiment, and as they passed through the place where he had disappeared, the dog had recognised the regimental uniform, and followed the detachment.”

But not all stories in the book are so pleasant, nor do they have such a happy ending.

“After day-break, while we were all talking together, Adjutant-Major Delaitre came up. He was the worst man I’ve ever known and the cruellest, doing wrong for the mere pleasure of doing it. He began to talk, and, greatly to our surprise, seemed much troubled by Béloque’s tragic death. “Poor Béloque!” he said; ‘I am very sorry I ever behaved badly to him.’ Just then a voice in my ear (what voice I never knew) said: ‘He will die very soon”. Others heard it also. He seemed sincerely sorry for all his bad behaviour to those under him, especially to us non-commissioned officers. I do not think there was a man in the regiment who wouldn’t have rejoiced to see him carried off by a bullet. We called him Peter the Cruel.”

Delaitre died the next day, from enemy fire, in the presence of Bourgogne and other comrades. His final words were, “For God’s sake take my pistols and blow my brains out!”

“No one dared do this service for him,” continues Bourgogne, “and without answering we went on our way–most luckily as it happened, for before we had gone six yards a second discharge carried off three of our men behind us, killing the Adjutant-Major.”

The book is invaluable for scholars but also for those who just love history. And one can’t help thinking that history repeats itself. Greed, the desire for power and glory, is always there. But also some pure feelings, “from war to love, and from love to war!” as Bourgogne says.

Leipzig (1813)

Poem by Thomas Hardy

SCENE. – The Master-tradesmen’s Parlour at the Old Ship Inn, Casterbridge. Evening.

‘Old Norbert with the flat blue cap –

A German said to be –

Why let your pipe die on your lap,

Your eyes blink absently?’

– ‘Ah! . . . Well, I had thought till my cheek was wet

Of my mother – her voice and mien

When she used to sing and pirouette,

And tap the tambourine

‘To the march that yon street-fiddler plies:

She told me ’twas the same

She’d heard from the trumpets, when the Allies

Burst on her home like flame.

‘My father was one of the German Hussars,

My mother of Leipzig; but he,

Being quartered here, fetched her at close of the wars,

And a Wessex lad reared me.

‘And as I grew up, again and again

She’d tell, after trilling that air,

Of her youth, and the battles on Leipzig plain

And of all that was suffered there! . . .

‘– ’Twas a time of alarms. Three Chiefs-at-arms

Combined them to crush One,

And by numbers’ might, for in equal fight

He stood the matched of none.

‘Carl Schwarzenberg was of the plot,

And Blücher, prompt and prow,

And Jean the Crown-Prince Bernadotte:

Buonaparte was the foe.

‘City and plain had felt his reign

From the North to the Middle Sea,

And he’d now sat down in the noble town

Of the King of Saxony.

‘October’s deep dew its wet gossamer threw

Upon Leipzig’s lawns, leaf-strewn,

Where lately each fair avenue

Wrought shade for summer noon.

‘To westward two dull rivers crept

Through miles of marsh and slough,

Whereover a streak of whiteness swept –

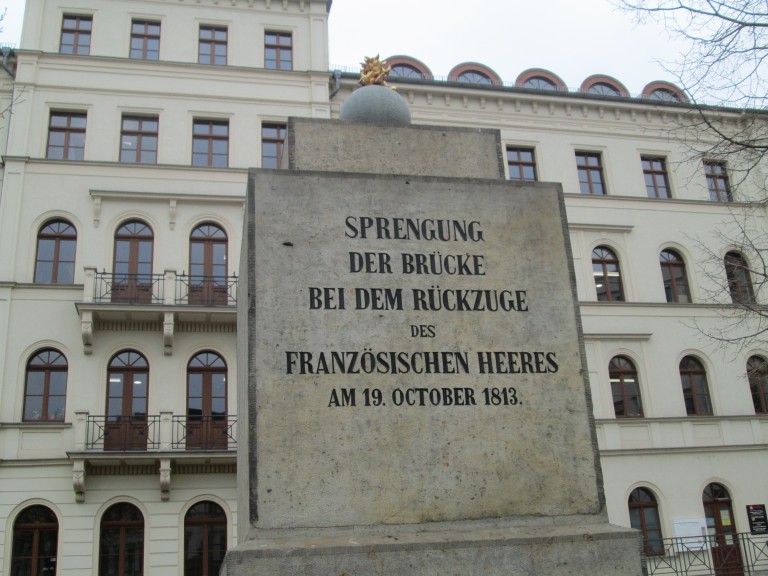

The Bridge of Lindenau.

‘Hard by, in the City, the One, care-tossed,

Sat pondering his shrunken power;

And without the walls the hemming host

Waxed denser every hour.

‘He had speech that night on the morrow’s designs

With his chiefs by the bivouac fire,

While the belt of flames from the enemy’s lines

Flared nigher him yet and nigher.

‘Three rockets then from the girdling trine

Told, “Ready!” As they rose

Their flashes seemed his Judgment-Sign

For bleeding Europe’s woes.

‘’Twas seen how the French watch-fires that night

Glowed still and steadily;

And the Three rejoiced, for they read in the sight

That the One disdained to flee. . . .

‘– Five hundred guns began the affray

On next day morn at nine;

Such mad and mangling cannon-play

Had never torn human line.

‘Around the town three battles beat,

Contracting like a gin;

As nearer marched the million feet

Of columns closing in.

‘The first battle nighed on the low Southern side;

The second by the Western way;

The nearing of the third on the North was heard;

– The French held all at bay.

‘Against the first band did the Emperor stand;

Against the second stood Ney;

Marmont against the third gave the order-word:

– Thus raged it throughout the day.

‘Fifty thousand sturdy souls on those trampled plains and knolls,

Who met the dawn hopefully,

And were lotted their shares in a quarrel not theirs,

Dropt then in their agony.

‘“O,” the old folks said, “ye Preachers stern!

O so-called Christian time!

When will men’s swords to ploughshares turn?

When come the promised prime?” . . .

‘– The clash of horse and man which that day began,

Closed not as evening wore;

And the morrow’s armies, rear and van,

Still mustered more and more.

‘From the City towers the Confederate Powers

Were eyed in glittering lines,

And up from the vast a murmuring passed

As from a wood of pines.

‘“’Tis well to cover a feeble skill

By numbers’ might!” scoffed He;

“But give me a third of their strength, I’d fill

Half Hell with their soldiery!”

‘All that day raged the war they waged,

And again dumb night held reign,

Save that ever upspread from the dank deathbed

A miles-wide pant of pain.

‘Hard had striven brave Ney, the true Bertrand,

Victor, and Augereau,

Bold Poniatowski, and Lauriston,

To stay their overthrow;

‘But, as in the dream of one sick to death

There comes a narrowing room

That pens him, body and limbs and breath,

To wait a hideous doom,

‘So to Napoleon, in the hush

That held the town and towers

Through these dire nights, a creeping crush

Seemed borne in with the hours.

‘One road to the rearward, and but one,

Did fitful Chance allow;

’Twas where the Pleiss’ and Elster run –

The Bridge of Lindenau.

‘The nineteenth dawned. Down street and Platz

The wasted French sank back,

Stretching long lines across the Flats

And on the bridgeway track:

‘When there surged on the sky an earthen wave,

And stones, and men, as though

Some rebel churchyard crew updrave

Their sepulchres from below.

‘To Heaven is blown Bridge Lindenau;

Wrecked regiments reel therefrom;

And rank and file in masses plough

The sullen Elster-Strom.

‘A gulf was Lindenau; and dead

Were fifties, hundreds, tens;

And every current rippled red

With Marshal’s blood and men’s.

‘The smart Macdonald swam therein,

And barely won the verge;

Bold Poniatowski plunged him in

Never to re-emerge.

‘Then stayed the strife. The remnants wound

Their Rhineward way pell-mell;

And thus did Leipzig City sound

An Empire’s passing bell;

‘While in cavalcade, with band and blade,

Came Marshals, Princes, Kings;

And the town was theirs. . . . Ay, as simple maid,

My mother saw these things!

‘And whenever those notes in the street begin,

I recall her, and that far scene,

And her acting of how the Allies marched in,

And her tap of the tambourine!’