As I type this from the comfort of my living room in Zentrum while drinking tea laced with oat milk, I must accept the fact that my wife is in a war zone. Fortunately, my wife is safe and likely will be for the foreseeable future. However, friends and family are not.

On Friday September the 25th, I flew back to Germany after spending two weeks with the in-laws in Yerevan, Armenia. We had planned to get together in March, but then COVID-19 happened. In mid-September, Armenia announced that flights for travelers could re-enter the country with a COVID-19 test, and my wife and I booked our tickets as soon as possible. There were basically no flights available. We ended up flying Belavia, the Belarussian airline. I thought flying through a country currently undergoing major protests would be the riskiest part of this trip. I was wrong.

I came back early, but my wife stayed longer to spend more time enjoying the late summer with family. That hasn’t panned out.

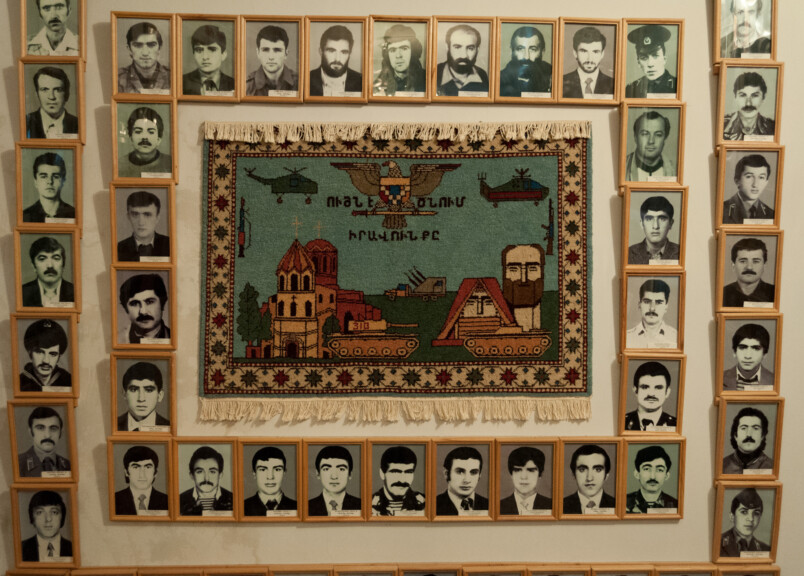

On the 27th of September, military shells struck the ethnically Armenian region of Nagorno Karabakh. Nagorno Karabakh has been a disputed territory since the early 20th century. When the Soviet Union was established, Joseph Stalin put the predominantly Armenian region in the republic of Azerbaijan as part of a policy to reduce nationalism and strengthen Moscow’s power over the republics. Both communities make historic claims to the land: Armenians have lived there continuously for over a thousand years, considering it a part of the homeland, and the predecessors of modern Azeris have lived there since the 18th century.

This unstable setup fell apart with the breakup of the Soviet Union, leading to a bloody war. What began with pogroms, became an ugly inter-ethnic conflict with civilian massacres and hundreds of thousands of internally displaced people. Armenians, both local and from Armenia, pushed back Azerbaijani forces and cemented their hold over the territory despite the Republic of Azerbaijan being larger and wealthier. In 1994, a cease fire was signed, formally ending hostilities until a peace agreement could be negotiated. No peace agreement was ever made.

To learn more about the conflict, watch the new documentary Parts of a Circle created by Armenian and Azerbaijani journalists. It’s considered the most thorough and neutral depiction of the conflict that there is.

This history came to a head this week. Frustrated with the status quo, Azerbaijan planned a major offensive against Nagorno Karabakh, recruiting Turkish jets and Syrian mercenaries to their already sizable arsenal. There have been attacks throughout the years (earning the conflict the moniker of a “hot” frozen conflict) but nothing on the scale of the current one. Instead of small-arms fire and sniper attacks, we have Soviet rockets striking the capital city of Stepanakert. Instead of having a few front-line soldiers catch a stray bullet, there are hundreds of soldiers dying and children hiding in bomb shelters.

And here I am on my comfortable couch.

Being an expat means one must get used to distance and a sense of powerlessness. Whether it’s important issues like domestic politics or something as mundane as taking care of a sick family member, expats are divorced from it. Sending thoughts and well wishes through screens, something we’ve come to depend on in the last six months, still doesn’t replace being there. A certain impotence is inherent in being an expat. This is magnified when being an expat in times of war.

While neighbors live their lives and friends make plans, I anxiously update Twitter, Facebook and Reddit. The last thing I do before going to bed and the first thing I do when I wake up is to check to see the latest reports on casualties and airstrikes. As I began with, my wife is safe, but we have friends and family serving in the military. I have scores of Armenian Facebook friends and as the fighting continues day by day, more of them post about someone they know who died in the fighting.

And here I sit, watching.

Growing up in the US, I don’t have any experience like this. To try to grapple the situation, I compare it to other issues where my individual actions seem trivial, like climate change. But one big difference between war and climate change is hate. No one hates the planet, not even polluters. Yet, hate is a major proponent that fuels this attack. And even when this fighting ends, the hate will still be there. The hate will be passed to a new generation that sees their friends and family die.

“Our goal is the complete elimination of Armenians. You, Nazis, already eliminated the Jews in the 1930s and 40s, right? You should be able to understand us.”

– Hajibala Abutalybov, Mayor of Baku at the time, now deputy prime minister of Azerbaijan, during a 2005 meeting with the municipal delegation of Bavaria.

I do what I can. I spread information about the war, which is part of the reason why I wrote this article. I donated money. And, I’ve contacted politicians to push them to intervene. If I were religious, I would also pray. Anything that seems like it would help, I would do.

My wife’s return flight has been rescheduled for next week, assuming it is not cancelled again due to security concerns. I will sleep easier when she’s back. But her return does nothing to help the thousands of soldiers and hundreds of thousands of civilians that are in harm’s way. Only geopolitics can save their lives, to which I feel powerless.

If you want to help, please raise awareness of this conflict with your friends, family and political representatives. You can also post on social media using the hashtag #NKPeace to promote peace in Nagorno Karabakh.

UPDATE October 11th 1:13 pm

Please note that Armenia and Azerbaijan agreed to a Russia-backed ceasefire that began at 10:00 CEST on 10 October. However, ceasefire violations occurred immediately afterwards with rocket strikes on the ethnic Armenian town of Hadrut. The foreign minister of Azerbaijan says that the truce is temporary and will only last long enough to exchange the dead. Whether the ceasefire holds or not, it’s clear the conflict is far from over.

Gabriel Armas-Cardona is a human rights lawyer. Born in Oakland, California, he has lived in New York, New Delhi, Yerevan and now lives in Leipzig. He’s passionate about human rights and regularly tweets about it @GArmasCardona.