Ich hab im Traum geweinet, (I have cried in my dreaming)

Mir träumte, du lägest im Grab. (Having dreamt you lay in your grave)

Ich wachte auf, und die Träne (And I awoke with these tears)

Floß noch von der Wange herab. (Streaming down my cheeks this day.)

Ich hab im Traum geweinet, (I have cried in my dreaming)

Mir träumt’, du verließest mich. (Having dreamt you left me.)

Ich wachte auf, und ich weinte (And I awoke and fell to weeping)

Noch lange bitterlich. (Long, lost and so bitterly.)

Ich hab im Traum geweinet, (I have cried in my dreaming)

Mir träumte, du bliebest mir gut. (Having dreamt you beside me)

Ich wachte auf, und noch immer (And I awoke, once more -)

Strömt meine Tränenflut. (My tears won’t leave me.)

In 2009, I returned to my hometown of St. Catharines, Ontario. I had been living in British Columbia for nearly nine years; they weren’t great years but, to me, they were necessary. I needed the time away from my brother and father, away from what I felt was their judgement and constant censure. In order to reconcile, to move on, I decided to return to the place in my past I had once feared and foolishly despised.

I moved in with my brother which seemed suitable at the time. He lived in a condo near my old neighborhood. In fact it was a mere five minutes away on foot. While I had schlepped around in British Columbia, a literary vagrant, still healing from a life-threatening illness, going from city to city and sometimes from neighborhood to neighborhood, job to job, my brother had merely moved around the corner. He worked for the government and commuted forty minutes to nearby Hamilton.

I liked his place. I liked the room he set aside for me and the rent was decent: four hundred Canadian dollars a month (about 300 Euros). Many people to this day tell me my brother was filching off me and yes he was but at the time I had no other options. Or felt I didn’t.

I bought a nice desk at an Office Depot around the corner, a futon and a used car. I thought I would start a wine consulting business, which would provide wine tastings and personal tours of the Niagara wine region with my brother as business manager. We set up a website and I wrote a blog. To gather up interest, I attended business functions, networking events and even joined a business professionals singles group. In all, I managed to put on one successful wine tasting evening in a nearby town of Jordan but all my other efforts were in vain. Even a Japanese girl I was seeing asked me what exactly I did. The fact that I didn’t know, that I was caught up in the hype for something ephemeral should have clued me in. It was all a hopeless endeavour.

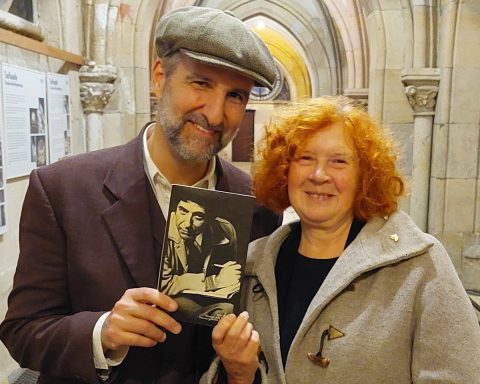

Yet I wrote my blog, wrote poems and read. I joined a local writing group and called the man who would be hosting the June poetry meeting. I must have spoken with R. for about an hour on my cell phone. I was on my way to somewhere, had only thought to make a quick call, confirming his address but instead sat in my car in the condo parking lot, door open and we talked about poetry for sixty straight minutes. It was like finding a long lost friend.

When I visited his home, his wife Z. was especially welcoming. Coincidentally, she was Ukrainian like my mother. While my grandmother was born in Saskatchewan, her parents had fled Dachau for the south of France then emigrated to Canada. There was even a picture on the wall of her mother and the resemblance to my own mother was striking – the same cheekbones, the same Oriental eyes.

Other poets gathered and I read my work, which at the time, yes, I’ll admit was a bit juvenile, immature and maudlin but I preferred my sentimentality to the other poems I heard that day. One man had written about a bumble bee in a classroom; another read a poem about soap slithering down his body, down through his buttocks. It was graphic, uncomfortable and I kept thinking who would want to read this for pleasure?

But then R. read and I felt this sense of reassurance. His poem was somewhere between Walt Whitman and Hart Crane, a bit of Song of Myself and The Broken Tower. The images were powerful and painful – he had written about the day he found out his son had committed suicide by hanging.

At first, I saw only the great outdoors, the camping trip with his wife. I could smell the fires and breathe in the sweet scent of the pine needles. I could feel the vertigo at the edge of a cliff before he jumped off for the waters below but then in contrast he described a polluted kiddie pool, the plastic marred in mud, standing ankle deep under a grey sky.

There was even a bit of Rimbaud in the poem, that sense of bitter intoxication. Listening, I felt bewildered. I reflected on his poem, thinking of an emotion so overwhelming and with it a longing to heal and change a single day. I couldn’t fully imagine the loss and I wondered, based on the poem about the pain, the inability to subdue it and to let it go. And in letting go, was there a fear you would let the person go, whom you longed to return?

There was a quiet after he finished; I didn’t want to speak for a long time.

The wine consulting ‘business’ fell apart and I soon left the poetry group. The man who wrote the soap poem was a wrathful individual, and while attending other group get-togethers, he purposely criticised other members. If his criticism had merit and was constructive, it was rare. Most of the time, his opinions were schizophrenic and if he complimented you to your face, he wrote something scathing on the poem you submitted for critique.

But out of the mess of 2009, R. and I developed a friendship. He became a kind of mentor and read my poems but with the idea of being supportive while critical. In the New Year, we took a winter drive, checking out wineries and I asked his opinion on a collection I had been working on and lent him to read. I remember we were on a country road, on the outskirts of St. Catharines, vineyards draped in snow flitting by, the sky that pale grey of early afternoon and yet it seems later, almost like dusk. He smoked in his dingy green Buick, a car he would never abandon as if by doing that he would let go of his son. I had rolled the window down and the salted scent of the road and crisp chill of the snow melded with his nicotine. He said to me: make your poems more tactile.

“What do you mean?”

“I get your poems but I don’t feel them. You’re holding back, dude.” He always called me ‘dude’.

“I saw you at the winery back there, and you know your stuff. What you do with wine, all that, you know, smelling, tasting, all you pick out in the aromas and flavours, all that stuff, do the same in your writing. Do that, dude. That’s all you need.”

I nodded.

“Do the same and put more feeling into it.”

I reflected on this and when I got home that afternoon, I knew I had a new mission.

I felt my poems improve and the times we met, which became far and few between, he told me more about his son. He had been quite the character but also troubled. While many of us have sensory filters, that we can block out the world to concentrate on a task, his son suffered from a kind of hyper awareness. While in school, he was distracted by the rain pattering on the window pane or the sound of footsteps in the hall behind him. He heard the pencils on the desks scratching, tapping and the restless shuffle of his school mates’ shoes, feet and legs juddering endlessly for recess. He was plagued by this constant overwhelming sense of hearing, feeling but only felt free when out in the country. R. described the bike rides they took, long excursions to Ottawa or Toronto and back. The more he talked, the closer I felt to an understanding of who his son was.

Then one night I dreamt about R. and his children. In addition to the son he had lost, he had a surviving daughter, a piano teacher who worked for the city courthouse. In the dream, they were young and it was winter. The trio were having a snowball fight and I seemed to be floating around the scene like a ghost or like the narrator in a short story, uninvolved. The snowball fight took place at night, near a country house and it was dark aside from the porch light; son and daughter ganged up on their father, sneaking up on him. He tried to hide in his car but they found him, opened the door and threw snowballs on his chest.

I heard their laughter in the dream and felt this incredible happiness, a bursting happiness only for the dream to suddenly change. I found myself on a bus and heard Russian spoken. I knew it was Russian, having studied a bit of the language while living in Vancouver.

For some reason, I understood and yet didn’t understand what was spoken because in the dream I began to cry.

When I awoke, my brother having long left for work, I sat at his dinner table and tried to piece together the dreams only to collapse into uncontrollable tears. From the snowball fight to the mysterious Russian I had heard, it was like something inevitable had broken though me. I had spent most of my teen years as a kind of emotional reclusive; I knew the illness had something to do with my self-repression. Perhaps I had cried for the eight years I had spent away, the years in and out of hospitals and for the weariness of accepting my business failure.

I also believed I had cried for R. and his son and of course, for his daughter who had suffered the loss of her brother.

The theme of crying in one’s sleep has fascinated me for many years. When I was living in British Columbia, I often dreamt I woke up crying when I hadn’t even yet woken up. The dream of waking up, of starting your day is so strange. There is something premature about our unconscious or is it maybe our conscious mind is so impatient, our sleep tells us a tale of what our day might be like to satisfy us.

I have dreamt of songs I couldn’t write while awake. I have dreamt of girls I once knew but will never see again. Yet, I have had so many dreams that were sullen when I was only dealing with a loss and the longing to retrieve what was gone.

I didn’t cry at my Opa’s funeral but in my sleep I seemed to meet him on countless occasions, to take long walks with him or sit by him in his living room, his cryptic Dutch crossword in his lap, his little clock tingling out the half-hour. In the dream it seemed we had walked for hours or sat for a long time but there was a sense of never enough. And when the time came for us to say goodbye, he always embraced me or we did our special handshake. Yes, so many times I have awoken surprised at the dryness of my eyes.

And as a result, certain poems have come to me with such a theme.

To end this blog post, I submit such a poem. This one is about a woman named Anna and feeling her relationship has fallen apart. I don’t think I have anything else further to say on the topic.

Anna’s Dream (Napoli)

Blue night, you set out with your

Boat,

Sails bright, the moon

Shredded, ripping

Down into the sea.

I stood at the dock;

My wet bathing suit,

A dark cocoon.

Pulling ropes,

Guiding the sails,

You returned to my

Wooden harbour but I

Had gone

Down to the beach.

You found my wet footprints

Where are you?

Lifting the sail, shards of the

Moon pierce into my heart;

Each a shattered reflection

As I walk along the blue beach

And you follow – we are parallel

My hand goes to my mouth

I’m going to cry in my sleep.