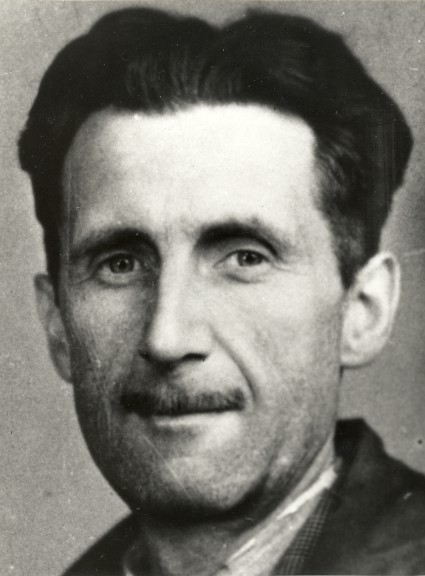

People have been giving late British novelist George Orwell a lot of credit for foreseeing the tribulations of our day and age. But he may have been describing a process already started in his own time, or a scenario that is perhaps merely repeating itself now. (After all, humans are slow learners.)

To me, rather than a prophet, Orwell seems more like a keen philosopher of (his own) routine and its potential to be infiltrated and harnessed by power, and then to engulf and kill – and that is part of what makes his work timeless. I don’t agree with everything the strongly opinionated author has written, but I’d like to discuss some of his writing I find particularly enlightening.

Orwell’s “prediction” of the end of our civilization did not involve fiery pestilence and chaos, but rather soul-destroying order. It’s a march perhaps already set in motion with the industrial revolution, and poetically tackled when Orwell was still a young lad, in Fritz Lang’s silent film Metropolis (1927).

Our dystopian 1984 selves are those of passionless, passive snitches controlled and oppressed via technology. Those of mere spokes in the endlessly spinning wheel of a surveillance superstate personified by Big Brother – no, not the TV show – grinding the few dissident into dust and feeding the few in power.

The author wrote his seminal 1984 – which has experienced an upsurge in popularity since Donald Trump’s election – in 1948. The novel was evidently inspired by Orwell’s own experiences and observations in the period around and during the two World Wars, which likely shaped his entire lifetime (1903-50).

His essays in the collection Books v. cigarettes, copyright 1984 (really), show a disillusionment with communism, but also a deep and personal awareness of how blatant class differences and social Darwinism were. Moreover, they show striking parallels with our present.

First, let’s look at Orwell’s contemporaries.

It’s strange to read something from or about people who are long-dead and with whom one can closely identify. The unkempt, procrastinating (but efficient in the last minute), overworked, badly fed, hungover, frustrated writer that is the protagonist in “Confessions of a Book Reviewer” (1946) is also a portrait of me on some weekends.

Another one of Orwell’s essays, “Bookshop Memories” (1936), fleshes out the passing characters with such insightfulness into the mundane that I could project them onto the people I myself see browsing at bookstores. It seemed to really bother Orwell that many didn’t seem to properly value literature, although they set out looking for it in the shop where he worked.

Back then and now, our routines and personas have been somewhat similar, including trying to sound smart to strangers while getting sucked into easy, brainless, cheap entertainment as well as money-depleting addictions (hence the “cigarettes” part of the collection title). People were forgetting about good books, or perhaps never bothered about them. The brainless, cheap entertainment used to appease the masses – a pacifier – is an important part of 1984.

We’ll also pass through and physically disappear like those book shoppers did. One day, if we’re (un)lucky to live that long, we’ll be somehow like the patients in a nightmarish hospital in France where the narrator once found himself during a bout of illness. (Makes one think of the harsh impersonality with which ordinary people were routinely treated in 1984.) If we end up poor, we’ll be even more like them, probably minus the medieval modes of treatment they had to endure (“How the Poor Die,” 1946).

Now, on to Orwell’s “prophecies” that were also (or actually) observations from his daily life.

His essays give the impression that Orwell, sicklier and of a lower social station than his boarding school peers, had felt inferior and like an outsider since he was very young. This probably helped give him superior observations skills over the folks born privileged, something the now legendary (and visionary) novelist used to survive and build his career on.

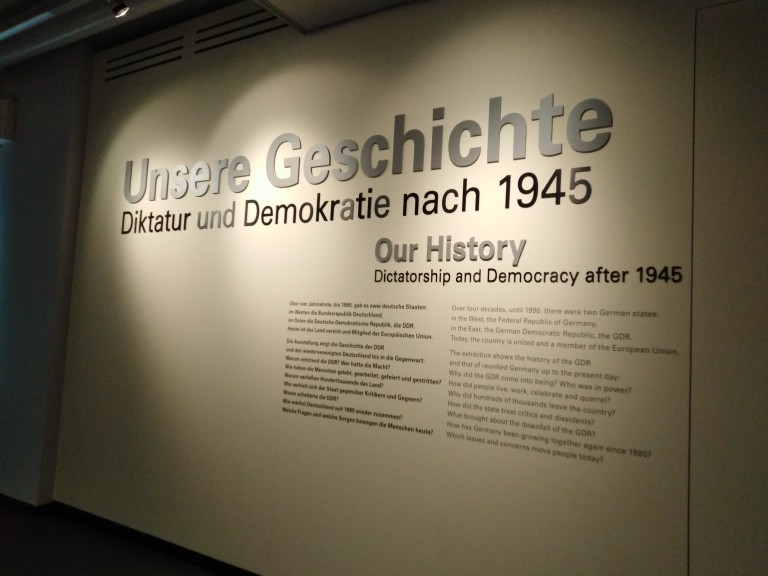

Perhaps even more haunting than pondering one’s own mortality through Orwell’s essays – which run from memories of childhood to middle age approaching the year of his death – is realizing how much the political ills of his post-WWII society may have resembled our own. I found this particularly evident in “The Prevention of Literature” (1946), which uses the UK, where Orwell was based, as a major reference.

The essay opens by talking about how censorship (of books and the press) had been a problem for centuries, and how people in the Britain of Orwell’s time avoided tackling the dimensions of the topic head-on, even in a writing industry event. Laws against obscenity were being attacked and defended back then, a bit like hate speech today.

The way Orwell described the plight of journalists and other writers in 1946 is also a portrait of now:

“The sort of things that are working against him are the concentration of the press in the hands of a few rich men, the grip of monopoly on radio and the films, the unwillingness of the public to spend money on books, making it necessary for nearly every writer to earn part of his living by hack work [under institutions that] help the writer to keep alive but also dictate his opinions” (p. 22).

Among other elements, Orwell was concerned about the Soviet Russians’ influence on “English intellectual life.” We are right now concerned about the Russians’ influence on contemporary American politics.

In fact, his essay refers to fake news in post-WWII England within such a context:

“The fog of lies and misinformation that surrounds such subjects as the Ukraine famine, the Spanish Civil War, Russian policy in Poland, and so forth, is not due entirely to conscious dishonesty, but any writer or journalist who is fully sympathetic to the U.S.S.R…. does have to acquiesce in deliberate falsification on important issues” (p. 27).

The author identified two groups of enemies of “intellectual liberty:” the “theoretical” ones, namely “the apologists of totalitarianism;” and “its immediate, practical” ones, which he dubbed “monopoly and bureaucracy” (p. 20).

Except that, in his time as well as our own, the totalitarian camp had actually made important “immediate, practical” gains in the Western world.

Back then, the “distorting effects” came from World War II. Today, they largely come from the war on terror.

People had been battered into giving up freedoms in exchange for the restoration of order post-WWII. We, in turn, were psychologically terrorized into doing so post-9/11. In both eras, many opinion-makers were either coerced, complicit or passive in letting this happen.

Even in times of relative peace, we are to believe there is a war on. As Orwell himself wrote in the same essay, the foundation of totalitarianism is lies – something that would remain even in the eventual absence of secret police and labor camps:

From the totalitarian point of view history is something to be created rather than learned.

“Totalitarianism demands, in fact, the continuous alteration of the past, and in the long run probably demands a disbelief in the very existence of objective truth. (…) The friends of totalitarianism in this country tend to argue that since absolute truth is not attainable, a big lie is no worse than a little lie” (p. 28).

Uncanny. Isn’t that precisely what the Trump camp is doing right now?

The totalitarian process starts with discrediting information sources and curtailing freedom of the press – which is also a major concern presently in the UK and the rest of Europe. As Orwell wrote: “What is really at issue is the right to report contemporary events truthfully, or as truthfully as is consistent with the ignorance, bias and self-deception from which every observer necessarily suffers. (…) A society becomes totalitarian when its structure becomes flagrantly artificial: that is, when its ruling class has lost its function but succeeds in clinging to power by force or fraud” (pp. 24, 33).

Perhaps the real tragedy here is that we have repeatedly been, in modern history, deceived by both the people we expected to deceive us and those we expected to bring change. The revolution shall be televised, and there will always be (apparent) winners and losers of it, who alternate between winning and losing.

Liberation and independence do not necessarily mean freedom.

We elect and we oust. Bliss, fear and disappointment wax and wane. Peace and war are part of the same industry. And so goes the cycle in our “democracies,” which Orwell so well understood. On and on.

For tidbits of Orwell’s views on current events of his life and times, read his diaries, published as blog posts 70 years after he wrote them.