To say that football in Brazil is a religion is an understatement, but it is also at the heart of its politics.

I traveled from Rio the Janeiro all the way up to Recife last March and April with my German girlfriend, and we saw people playing football (or soccer for Yanks and Aussies) in pretty much every free plot of land. Beaches are especially popular makeshift football fields.

Moreover, getting to a conversation about football is as easy as finding a hipster in today’s Leipzig. Everyone will talk to you about football, especially if you tell people that you live or come from Germany…

The national tragedy

7 a 1, or 7-1. That was the almost universal follow up after answering the customary “where are you from” question posed my locals. The pronunciation of these two numbers in Portuguese by the locals transformed the welcoming smiles of Brazilians to long sad faces with teary eyes.

Brazilians everywhere are traumatized, seriously traumatized, by the seven to one defeat of A Seleção to Die Mannschaft. You may remember the debacle in the semi-finals of the 2014 World Cup, held in Brazil for the second time (the first was in 1950, when Brazil lost in the final to Uruguay, by a measly 2-1).

In Belo Horizonte – home of the Mineirão Stadium, where Brazil’s worst national tragedy occurred – a cab driver told us that “here we cannot talk about Germany.”

Panem et circenses

Besides the trauma of Brazil’s exit from the last FIFA World Cup, talking about football quickly descends into the realm of politics.

Most Brazilians love football, but they also love to criticize their politicians. They do this with good reason: A country where living costs are almost as high as Germany’s has a minimum wage of less than 250 euros per month.

Another cab driver in Belo Horizonte told us that Brazil will win the upcoming World Cup in Russia, and not for the best reasons:

The government is investing a lot of money in the national team so that they win the World Cup, but that’s because presidential elections are coming up in the fall. They need to keep the population happy.

A tour guide in Rio de Janeiro, the Cidade Maravilhosa or Marvelous City (which definitely lives up to its nickname), told us that Brazilian politicians long ago invented the world-famous samba festivals and football tournaments to keep people happy in the midst of economic hardships.

The reference always went back to the ancient Roman political tactic of giving the people panem et circenses (“bread and games,” or literally “bread and circuses”), while politicians enjoyed the spoils of government.

The Maracanã Stadium in Rio is hallowed ground for all football fans. However, for many Brazilians critical of how politicians use football as a tool of social appeasement, these stadiums are a sort of Colosseum, a symbol of “bread and games” politics.

Brazilians protested the building of stadiums like the one in Manaus, a city in the middle of the freaking Amazon! It cost about US$400 million, and it only saw four games in the entire 2014 World Cup.

People demanded that public money be spent on social services like education, instead of a huge stadium in the middle of the world’s biggest rain forest. Fair enough. But although the anger felt by Brazilians regarding state spending during the World Cup is understandable, the root of the close relationship between football and politics in Brazil goes beyond a mere social appeasement tactic: It embodies the very history of the Brazilian Republic.

Football, politics and the racial divide

Brazil was among the last countries to end slavery, in 1888. As Brazilian historian Laurentino Gomes explains, by the following year, 1889, the end of slavery had brought down the monarchical system it supported.

Not only did this event bring a horrific institution to an end, but it also changed the entire country’s economic landscape. Slavery was the backbone of Brazil’s main industry during the 19th century: coffee exports.

At the time slavery was abolished, lots of boats with European migrants – mainly from Italy, but also from Germany and Great Britain – arrived in Brazil to escape famines and political turmoil in Europe. Brazilian landowners employed these white migrants instead of the freed black population. This led the black population to unsuccessfully seek employment in cities.

Thus, Afro-Brazilians have remained in structural poverty until today, populating the favelas or slums around major cities like Rio de Janeiro. Moreover, the end of slavery and new immigrant influxes allowed for manufacturing industries to pop up.

Football came into play amid this changing social landscape – of almost half of the population being freed and seeking work in the cities, the influx of European migrants, and the creation of new economic industries.

It was in this scenario that football became a national institution in Brazil.

As a football fan(atic), my favorite museum in Brazil was the Brazilian Football Museum, housed in none other than the Mineirão (as already mentioned, the site of the 2014 7 a 1 national tragedy). This museum excellently tells the history of football in Brazil. (Interestingly, though, it has completely omitted the 2014 World Cup. The museum’s organizers erased the 7-1 defeat at the hands of Die Mannschaft from history records.)

In this museum, I learned that the massive inflows of European migrants led to the introduction of many sports like cricket, rowing, cycling – and of course, football – to Brazilian society.

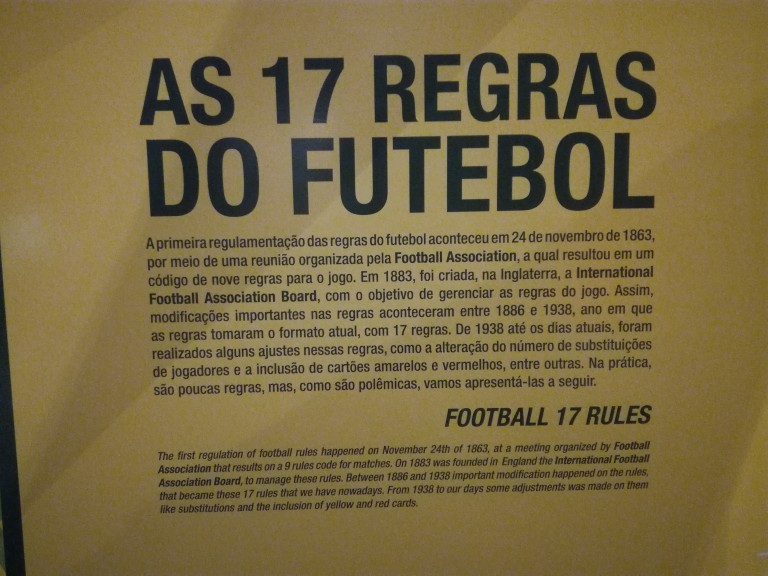

The official record is that in 1894, Scottish-Brazilian student Charles William Miller traveled to São Paulo with 2 rubber balls, an air pump, and a booklet with the 17 (sacred) rules of football published by the England-based Football Association.

In 1895, the first recorded football game in Brazil took place in this city, between the São Paulo Athletic Cup and the São Paulo Railway Company. Teams were composed of a mix between British and Brazilian players. Miller played for the latter team, which won the game 4-2.

Football in Brazil quickly became a sport that cut across class and racial divides.

In England, the birthplace of the beautiful game, football came to popularity in the midst of the industrial revolution. People of different social classes played it, and it became a space of social mingling.

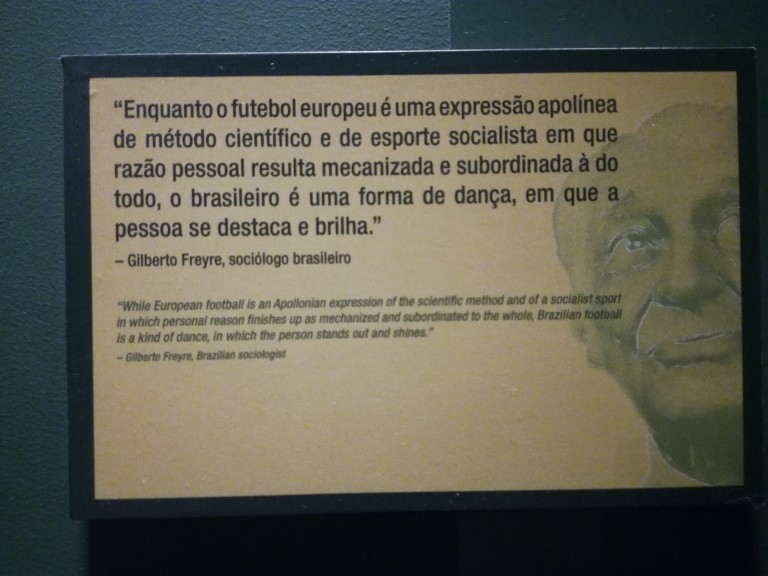

Something similar happened in the South American country. Football became a space for the new Brazilian Republic, with its large freed slave population, high inflows of European migrants, and a changing industrial landscape, to come together. This is why the famed (and controversial) Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre explained that football became “a truly national institution.”

In today’s Brazil, football remains at the heart of its society and its politics. But the claim that reduces football to a “bread and games” political tactic appears rather unfounded.

Football is deeply rooted in the formation of modern Brazil, and not just the creation of power-hungry politicians. Once again, cynicism by the population vis-a-vis football is understandable, given the political and economic turbulence that the country is undergoing.

It also shows that one often cannot separate conversations about football and politics in Brazil, as the beautiful game is a central component of the South American giant.

Related: Where to watch the World Cup 2018 out and about in Leipzig