If you grew up in Germany and went to school here, you learned deeply about the Holocaust, a racial terror campaign during Nazi Germany. You have probably visited concentration camps like Buchenwald (an hour’s drive from Leipzig), and at least some of the many outstanding museums in the country about the subject (such as the Jewish Museum in Berlin or the Dokumentationszentrum in Nuremberg).

In other countries, like the United States, history classes at the high school level would often treat events of racial terror like the Holocaust as one more historical fact: Hitler came in the 1930s, then he gassed six million Jews to death towards the mid-1940s, D-Day happened in 1944, then the Nazis surrendered in 1945, nuclear bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the same year, and then the course would move on to the Korean War.

In an interview with visiting researcher and human rights lawyer Terron Ferguson, we talked about how we both happened to have gone to high school in Miami, Florida, and that history class tended to just teach students the “dry facts” not only regarding these atrocities, but also the United States’ own experience with racial terror. This refers to slavery, and the long and painful historical legacy that this “particular institution” (as it was called in the South) left in America.

Ferguson was awarded a visiting fellowship at Leipzig University to find out how the German experience with learning about its (racial) past can be used in the US.

Germany has been a lot more successful in remembering its painful past than the US has. This success is evident not only in high school classrooms, but in many public spaces where cultural initiatives are effectively used to make sure past atrocities are not overlooked or forgotten.

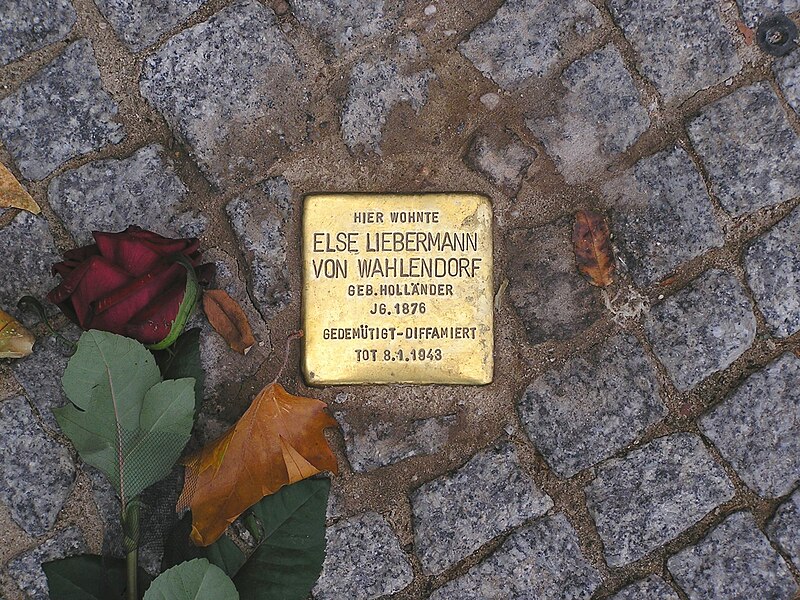

If one takes a stroll in any German city, it is hard not to come across a Stolperstein, the golden stones found in front of the houses of victims of Nazi extermination or persecution. They display the name, date, and fate of the victims of racial terror. These small monuments go a long way in making people remember these horrors, so that they never happen again.

The idea to bring the German experience with memory culture to the US is not new. In fact, Ferguson explained that his old law firm, the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), built a lynching memorial to remember the victims and survivors of racial terror in the American South. Mobs of white southerners would publicly lynch, or execute, black people.

This practice of racial terror in the American South continued after slavery was abolished in 1865. It is both a source and a product of structural racism in the US.

But Ferguson further elaborates that, in learning from the German experience with remembering its past, one has to be aware of the difference in contexts when trying to push for similar projects in the US. In reference to Stolperstein, Ferguson said:

“Germany has a strong history of preservation. Marking the sites of lynchings in the United States is difficult because they often took place in open fields, where today a Walmart stands.”

The EJI developed an interactive map showing the places where racial lynchings occurred. However, physical symbols, and not just a website, are needed to cement a culture that memorializes (past) atrocities like racial terror.

What to do, for instance, with the statutes and symbols of the Confederacy all over the American South?

In the southern US states, it is not uncommon to find statues of military leaders of the pro-slavery Confederacy, such as Civil War icon Robert E. Lee, as well as streets named after them. But for many – especially for African-Americans – memorializing such figures represents an approval of racist politics.

Many in the US have organized to remove such public symbols of the Confederacy. At the same time, their actions have led to much political resistance. Republican lawmakers in Tennessee, for one, withheld funds from the local government in Memphis after the city removed two Confederate statutes. One of those statues was of the first leader of the Ku Klux Klan.

Ferguson pointed out that “in the state of Alabama, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. day – despite being a national holiday – is also celebrated as General Robert E. Lee day.”

He also argued that in the US, teachers, museums, and the media should tell history holistically. They should describe the complexity of the issue and avoid singling out one narrative over others.

Ferguson sees the history of the American Civil War as a good example. One cannot simply explain it as the struggle over slavery or over state rights:

“The civil war broke out because of slavery, state rights, the changing role of labor in the 19th century, the industrial revolution; no single factor explains it fully.”

His words resonate with that of the great author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who said that telling only a single story is very dangerous when trying to understand a person or a society.

For Ferguson, the removal of Confederate statutes from public spaces is neither enough nor necessary.

The bottom line is that to memorialize racial terror in the United States, and to prevent it from happening again in the American context, history needs to be told through its many stories and not just one. This includes how racial terror led to the violent lynchings of hundreds because of the color of their skin, among other horrors, and how the majority white population has become increasingly isolated, which also increases the likelihood that they will support radical political positions. Hence, removing Confederate statutes, by itself, is not the solution, according to Ferguson.

One obstacle that Ferguson identifies in telling the story of racial terror in the US, in contrast to Germany, is the government’s level of support for cultural memory projects, like museums and memorials.

“In Germany, most museums are state funded; there is a ministry of culture funding and curating museums and public memorials about the Holocaust,” said Ferguson. “In America, one considers culture as entertainment. Until there is public support for museums and memorials, telling all the narratives of America’s history, then we cannot come to an understanding of our past.”

And of course, this includes coming to terms with its past of racial terror.

About the interviewee: Terron Ferguson is a human rights attorney who is a German Chancellor Fellow with the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

He is researching the Holocaust, World War II, denazification, and contemporary German history. In the fall, he will release an animated film, pamphlet series, and exhibition that examines what the United States can learn from Germany about collective responsibility, truth, and reconciliation for past injustices.

This work is merely the beginning. Ferguson hopes to pursue a PhD investigating the rise of international extremism, namely in Europe, the United States, and the United Kingdom. He will apply the learnings from German history in order to create and operationalize a set of modern discourse ethics and practices for civil society to communicate more honestly, healthily, and productively.

Ferguson encourages those interested in helping with his work in any way, such as sharing their own experiences, to email him at terron.i.ferguson@gmail.com.