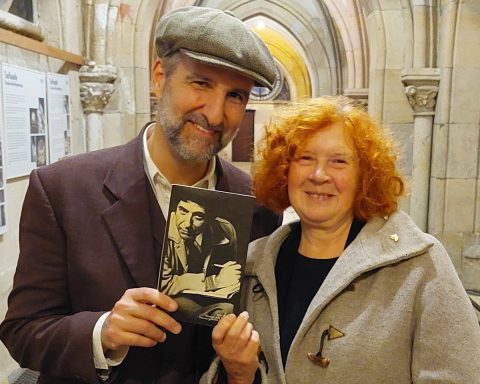

Literary Parlor Part III: Omar Sabbagh

In our column Literary Parlor, we invite international award-winning authors for a virtual cup of tea, coffee or whisky, to unveil some of their art and craft secrets. Today we talk to the brilliant author and literary scholar Dr. Omar Sabbagh, London-born of Lebanese parents and now a resident of the UAE, where he is Associate Professor of English and Creative Writing at the American University in Dubai. Sabbagh moves in between the worlds of writing academic papers, poetry and prose. He has published two novellas, the Beirut-set Via Negativa: A Parable of Exile (2016) and its Dubai-set sequel Minutes from the Miracle City (2019). Among his collections of poetry are My Only Ever Oedipal Complaint (2010), The Square Root of Beirut (2012) and his latest, But It Was an Important Failure (2019).

Interview by Svetlana Lavochkina

You are an English writer of Lebanese background. Did your origins shape your creative path?

Yes, they most certainly did. Not in terms of some predominating thematic concern with the Middle East, necessarily, but because of the ethos evinced by my parents (genes, of course, as well as deep nurturing.) In particular, my mother. She, like my father, studied Economics (unlike my father, only undergraduate) but had always a passion for English and English literature. Thus, as you might expect, from a young age, 11 or 12, I was a deeply avid reader.

She gave me books by Austen and Dickens, which I devoured, quite pleased with myself, as ever, to boot. And I even recall attempting to write a book like Austen’s Pride and Prejudice at that approximate age: but I only wrote one chapter and, needless to say, it was derivative!

So, the matrix by which I was plugged into the earth of English was always (and always going to be) thick with keys and notches and, no doubt, knots.

All that said, I didn’t start writing with any professional ambition till my early twenties. Between the ages of 15 and 20, I was keen on all sorts of things in the Humanities, apart from novels and other literary texts, and it wasn’t until I near-flunked-out of my BA degree at Oxford, that, whether with executive force, or from sour grapes, I decided I was to be a literary writer in the main; a (somewhat) lazier kind of philosopher.

Finally, I should say that this support and supportiveness (from my parents), financial as otherwise, was there and available to and for me across much of my postgraduate experience; so that, yes, there too (theirs too), in its own way, my ‘origins’ helped and helped shape my various literary paths.

In your florally-rich, complex poetry, of which I’m a great fan, you underpin private, confessional elements with a sublime, detached voice of your lyrical hero, chameleoning your style to echo your favourite authors at times. Yet, I would recognize your voice unmistakably. How did you forge your author’s hallmark?

In poetry, as in prose (of whatever genre), my first and most foundational instincts and/or concerns are with words.

The impetus or animus that goes ratcheted behind nearly all my writing, comes from, dare I say it (and without irony, mainly), my ‘relationships’ with (English) words. Because I do have relationships with them, experiences of heartbreak and of joy, with them. So that, any successful effecting of my ‘voice’ (and with reference in the main to poetry here), is actually a bubble-like network between my mind and that language. Which is not to say my poetry is lexically dense or complex, but is to say I hope, to a certain extent at least, pure, purified and (one hopes, though it’s unlikely) purifying.

I get a kick from deploying words, even the simplest ones. When I do, I almost feel a system of branches or roots reaching down from my head into some (again) matrix: I can feel most of my words detonate against a board, wall, or like triggered mines.

Now, I would say, too, as you so perceptively intimated in your question, that I have internalised (like any writer) certain other, previous ‘voices’, and that sometimes I use those structures of feeling like props upon which to build and, in the end, I hope, go my own way. This, for me, just is what creativity is: it is not (Coleridge) ‘fancy’ or fanciful, but ‘imaginative’. And this means that ultimately, in my poetry as elsewhere, coherence and integrity are keys to how my mind works on the page. Call me old fashioned, and I probably am, but I’d rather a mediocre poem that has and deploys unties of reflection and/or feeling, say, rather than a much richer artefact that may be seen to lose its way.

Sublimity, as you mention, is also key for me. I’ve less to do with beautiful or opulent imagery, and more to do with attitude, tone, voice – which, unfortunately or not, for me are always trying to ape some kind of virtuoso status. I suppose those last two comments are in slight tension, but heyho!

And the last thing to say is, my heroic lyrical persona feeds and is fed by my ear more than by my eye, though both are of course effecting, operative; in fact – as per the closing ironies of my 5th collection – being confessional most of the time, it really isn’t any particularly compelling story I have to tell that counts in my verse; it is, one hopes, merely the story of a mind obsessed by craftsman’s ship(s).

Your prose persona is very different from your poetic persona. Could you comment on the differences as you perceive them?

In critical prose, I don, again, another heroic persona – and that heroism reaches at times into my syntax. Often, I allow myself (regretting it at times) to personify in a well-nigh (Neo-)Hegelian manner abstractions, where verbs will be enacted by things which are not really agents. And syntax is key for me, as a prose writer, because it’s the way rhythm and music, tone and attitude, breathe spirit through the letters. In that sense there is a poetic commonality between my verse and my critical writing.

In my short fiction, I write in different ways, depending on what kind of effect(s) I’m looking for, or that’s looking for me. I can be Durrellian, Waughian (Fordian), Naipaulian, or what have you, depending. However, what I would say is, in spite of that last comment, that my prose is where I really do inhabit a space that is close to unique to me. The stakes are just as high as poetry, but they are also less high – which the latter always means for me (I won’t go into the twisted psychological mechanism) I make more of an effort with prose, invest more time, because I’m less likely to lose there.

Geography plays a crucial role in your work. Your novella “Minutes from the Miracle City“ has given me a deeper understanding of the real Dubai than any city guidebook would. Are you intending to write another place-based piece?

I’m currently working on my first full-length novel, but whether it will end up being successful or not, I’ve no idea. And yes, it is to be, with weird and impossible hopes, the ‘Lebanese’ novel.

Its main theme, in different ways, is at-one-ment. Places are repositories for character(s). And in the end, where my fiction succeeds, tends to be in three places: character, thematic insight, and prose felicity. Plots, I’m weakest with. And this is because, a book-bound bibliophile, I have tended until very recently to base my writing in the orchard (harbour) of my own mind, and have not, as one should, really, to be a successful writer of book-length fiction, ventured outwards to others and their stories and experiences and ways of living their life-worlds.

This is changing now, and for the better. My Dubai novella, which you mention, for instance, has near-zero autobiographical reference, and displays the stories and the storying(s) of a host of very different characters, picking out different ethnic and socio-economic berths in this tolerant, tolerating and multi-cultural Emirate of Dubai.

Do you differentiate the pleasures you draw from writing fiction, non-fiction, poetry (if we, say, speak in the Liquor language, or in the language of international cuisine)?

Great question, again; and I’ll recoup by returning to some of the territory of question 1.

In prose I am far more overtly sophisticated. In my poetry I want to move people and/or make them think (apart from the previously-mentioned, more personal concerns). This latter means, I rarely push any aesthetic boundaries. I want my verse to have integrity and be understood by most, at least.

As a poet, I am certainly not writing for other poets, or literary people, alone; though, I do often think it is only the latter types who may appreciate what is successful about my otherwise quite simple verse. So that yes, I write with different audiences in mind, and with different publishing venues in mind at different times. I’d like, ideally, to deploy my most sophisticated self all the time, but I have a family now, and I need to reach any and/or all interested readers, and not some overly-educated clutch of ivory-tower denizens!

Liquor is good, but so are burger and fries; filet mignon, though, is where I hope to reach: or parfait, because everyone loves parfait.

As a writer, in nearly all my practiced genres, I am, to repeat, recoup, merely a lazier philosopher. But then, so much that is good chances on one beneath the tree of idleness…