How to bore an audience: provide one-dimensional characters. So many of us are pigeon-holed and stereotyped. In her multimedia performance, Voices of Women (Stimmen der Frauen), Michiko Saiki examines the multiplicity that is woman. We are not just baby-making machines. We are living, breathing creatures with unique stories to tell. Look into our eyes. Read our lips. Hear our voices.

The audience filled with 30-somethings was not bored. And surprisingly, it was made up mainly of men.

Female Bonding with Michiko

In 2020 Michiko Saiki, Guilia Lorusso, Eiko Tsukamoto, and Farnaz Modaressifar had five days together at Royaumont Abbey in France. They spent time getting to know each other individually and collectively. They talked about anything and everything. Nothing was off-limits. These conversations extended to long sessions of vocal improvisation. That’s when you really get to the core of another being.

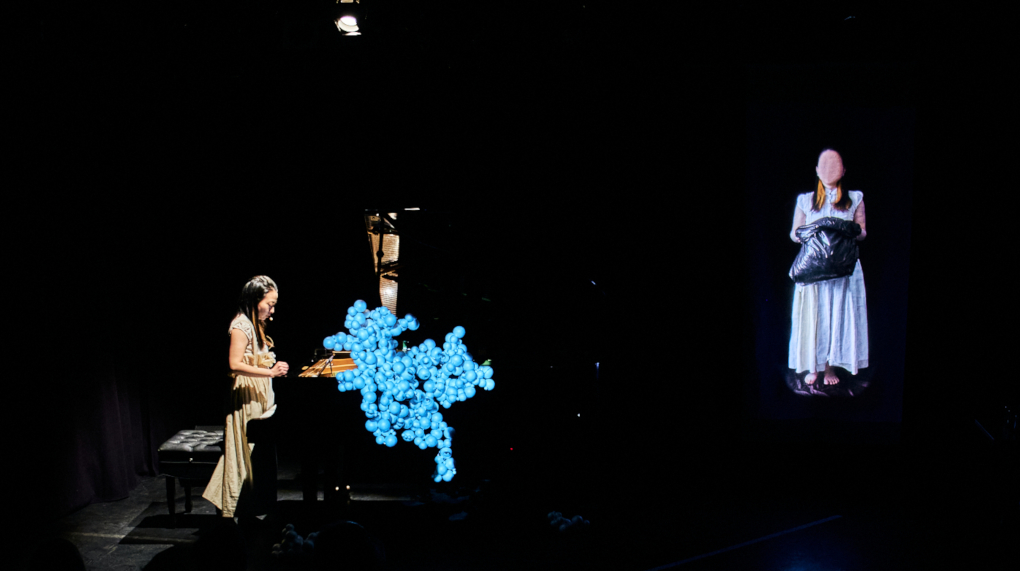

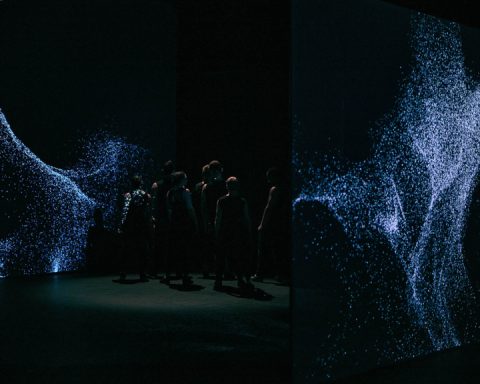

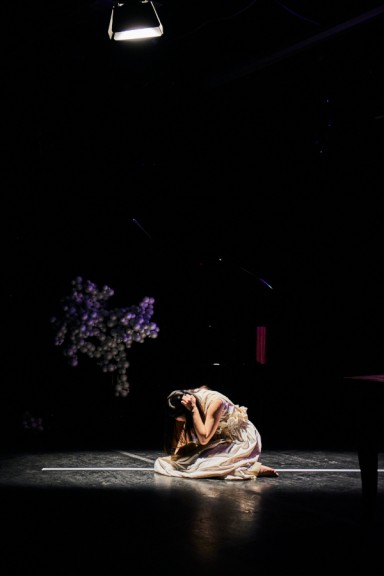

As we entered the performance at die Nato, some of us were given glasses of soil. We were also asked to write down our names and asked how to pronounce them. These two simple acts connected us from the moment we entered. This well-thought-out simplicity extended throughout the entire piece on every level. A minimalist stage with a table upon which sat a plastic bag, a video projection on a banner, a diagonal line of white gaffer tape on the floor, and a piano with a sculpture on it. The micro-glitch sound matched.

The Power of the Voice

Throughout the performance, the sound went back and forth between the speakers, the piano, and Michiko’s voice. As she notes, the voice is what we relate to. It has the ability to draw us in or repel us. It can make us feel a wide range of emotions and can afford us an unmatched intimacy.

Through spoken word and song we are empowered. I think the Emily Dickinson line used in Giulia Lorusso’s piece says it best:

We never know how high we are

Til we are called to rise

We had the opportunity to interview Michiko about Stimmen der Frauen and she provided insight into the vocalizing pianist genre.

LH: What is the concept behind Stimmen der Frauen, and why do you present this performance as a multimedia event?

MS: When I encountered the piece (speak to me) by Amy Beth Kirsten in 2013, my world was forever changed.

I had performed vocalizing pianist works before, but they were all written by men.

Thus, they mostly dealt with male characters or showed male perspectives. However, (speak to me) was written from the perspectives of Echo and Juno, from the Greek mythology of Narcissus. Embodying these characters and retelling their side of the story, I felt that my existence as a female pianist was validated, valued, and empowered for the first time in my life. This experience led me to think that this genre has enormous potential. It could develop into something powerful that can empower women and girls of future generations.

This is how I began working with female composers, trying to access their personal expressions through the medium of the vocalizing pianist.

The idea of making this a multimedia performance is a relatively recent development. It has to do with my personal interests as an artist. This genre automatically involves some elements from performance art, which I was heavily involved in back in 2011-2013.

I became interested in this genre due to my passion for performance art.

My creative outlet shifted into experimental video art and photography at the beginning of 2014. (I was filming myself, so in a way, I continued with performance art in my own videos and photography.) In 2015 I had my first tour with a program solely featuring vocalizing pianist works, in the US. This was before my dissertation research and I presented it as a regular concert. I moved to Leipzig in 2016, working on my dissertation research.

When I finished my dissertation in 2017, I was invited to do a project with some of the composition students at Hochschule für Musik und Theater Leipzig. I proposed to work with the female students in order to implement my dissertation research into practice. This was the beginning of Stimmen der Frauen. It was a natural progression for me to combine my passion for performing and video art. So I pitched it as a multimedia project and created a 60-minute quasi-theater show.

But at this point, all the elements were not 100% integrated yet.

The video element was projected onto a regular projection screen and it felt like something was missing.

In January 2020, I hosted an artist residency at Royaumont Abbey in France to work on a new edition of Voices of Women. I invited four composers there to work with me. On the first day, I invited a stage director, Alexandra Lacroix, to have a workshop with us. She said to me at the end of the session, “I watched your performances on YouTube. It’s very interesting, but I think you are too focused on the piano and you’re trying too hard to be a pianist. Is there any way you could include the piano, not as an instrument, but as an object that exists in space?” This question intrigued me. The next day, I was determined to create a video sculpture to turn the piano into a giant object that has meaning on stage.

I made the piano into an object that plays a role in my narrative.

Suddenly, the performance became more like performance art, with which I feel at home. It was so much easier to create a seamless performance. For the first time, I could integrate all three of my creative outlets – performance art, video art, and piano performance.

It felt natural to me to turn this project into a multimedia performance. I knew for sure that I could make it more powerful and meaningful by using the multimedia element effectively.

LH: You have performed in many different countries across Europe, as well as in the US. You also work with artists from a wide variety of ethnic and cultural backgrounds. Which cultural similarities and differences have you perceived in how gender is experienced and expressed through music and art?

MS: The more I work with composers from all over the world, the more I notice that the cultural background or their upbringings are only a tiny portion of the information that helps me understand their taste or aesthetics. It can influence them, but this information never determines or confines them as artists. In other words, each person has their personal language, and I can’t generalize or pin down any specific tendencies.

The perception of gender is always significantly different on a personal level.

Some people are very hesitant about gender as a topic and some are very enthusiastic about it. Some began to think about their gender more after being involved with this project. I think it’s always great to provide a safe space for people to wonder about their creativity and new possibilities freely. I’d like to be someone who can provide such a space for them.

I find it interesting that some audience members have more problems with the form of this project than the fact that it deals with gender as the topic. I think some people feel uncomfortable when they cannot categorize what they are experiencing. For some people, contemporary music itself is very new to them. On top of that, my performance isn’t just about music, it is not quite a concert but it’s not totally theater, either. This feeling of “I don’t know what I am seeing” sometimes makes people uncomfortable. But at the same time, it frees us from pre-conditioned expectations. It opens the door to new aesthetic criteria, which can still remain untouched by the ghosts of master composers.

Leipglo: What does it mean to you personally to identify as female in the music and art world?

MS: I’m proud of being a woman and I enjoy being a woman. I think being a woman is awesome. It hurts to see talented female composers who have great ideas but don’t have the courage to enter competitions or ask people to play their music.

The idea that “I’m not good enough” haunts them; the feeling is way too familiar to me, too.

My project is not only about creating a space for their unique expressions, but also about building a community for female composers. Where they can feel support for their work. I love working with women and it has been a blast! My fellow women artists/composers should embrace how great they already are. I present their work with confidence and pride. I believe and hope that these steps will cultivate a better musical environment for women.

LH: You wrote your doctoral dissertation on embodying the gendered aspect of performing as a vocalizing pianist. Why is gender relevant in musical performance, especially in vocal performance?

MS: Gender is relevant to any of the art forms that involve the body.

Consciously or unconsciously, we all categorize someone based on how they look or how they act. The degree of awareness is, of course, different depending on the person who perceives it. The voice reveals more about the person who is performing on stage. It helps to bring the element of body and gender more into the foreground of the whole experience. That makes the audience more aware of their own ideas of gender. Those performances can possibly work as a mirror, reflecting the audience’s own notions of gender. The vocalizing pianist genre has the potential to dismantle stereotypes and to question our unexamined stereotypes and gender ideologies.

About the Voices of Women:

This is the third installment of the Voices of Women project. The pieces are the result of a 5-day residency at Royaumont Abbey, France in 2020. Through this residency, I sought a new way of collaboration that challenges the traditional performer-composer relationships. Our working process began from learning about each other. I had one to two hours of daily sessions with each composer. In these sessions, we shared life stories, memories, and whatever interested us at that moment. We also sang and improvised together as a group. Sharing this intimacy, we felt a sense of community and appreciated each other on a deeper level. This allowed the composers to write a performer-specific piece and I could interpret their work with a deeper understanding.

I don’t usually specify an overarching theme for the whole performance.

I want each composer to express themselves freely and find/use their own musical language.

Therefore, I am fully responsible for sewing the pieces together to create a seamless performance. This year I used my own personal narrative to unify the performance under the theme of acceptance and affirmation. I reuse some of my earlier performance-art elements and combine them with the newly-developed video sculpture.

These pieces are all written by women, but how and what they think and how they express themselves differ completely. I cherish these differences and present them together as a collective for the betterment of the musical environment.

Michiko Saiki’s Stimmen der Frauen

With compositions by

Farnaz Modaressifar

Victoria Jordanova

Jue Wang

Eiko Tsukamoto

Giulia Lorusso

Presented by Contemporary Insights.